HISTORICAL SKETCH OF QUEENSLAND

Atlas Page 56

By W. H. Traill

FREE SETTLEMENT

THE destined hour had now arrived. The kiss of free colonisation aroused the fair territory from the long lethargy imposed by the restrictions of penal settlement. In February, 1841, Sir George Gipps, in a despatch to Lord John Russell, expressed himself rather as submitting to superior authority than as personally anxious to initiate the untrammelled career of the new free community. The land of Moreton Bay he reported to be good, and he awaited orders before offering portions for sale. Investors, he confessed, were ready; but he could not refrain from a somewhat querulous reminder that to throw open the district would involve trouble and expense to the government of the older settlement. A prophetic foreboding of a future separation seems to have prompted the question whether New South Wales was "to derive no compensation for the withdrawal of population and capital which the opening of such a settlement must occasion." In March the governor proceeded to Brisbane, and personally supervised the final preparations and the survey of the town. In July the first sale of Brisbane town lots was held in Sydney, and realised, for thirteen and a half acres, four thousand six hundred and thirty-seven pounds ten shillings, being at the rate of three hundred and forty-three pounds per acre. In December the machinery of free government was started. The days of "commandants" were definitely ended by the appointment as police magistrate of Captain Wickham, R.N., an officer who had done excellent service in coastal explorations by sea. At the same time, Dr. Simpson was appointed crown lands commissioner of Moreton Bay and Mr. Christopher Rolleston to the same post in the frontier district of Darling Downs.

Henceforth the story to be told is one of progress and expansion regularly accelerating. Industrial enterprise flowed into its natural channels. The timbers of the coast country, condemned by an English dockyard report, were appreciated by colonial builders, and their exportation began to constitute a trade with Sydney. The pastoral pioneers pushed farther and farther outward. The townships at Brisbane and at Ipswich, the latter then still known as Limestone, had been surveyed, and began to assume definite form and considerable proportions.

Among the most enterprising of these hardy pioneers were the brothers Henry Stuart Russell and Sydenham Russell, runholders on the northern part of the Darling Downs, whose excursions had extended occasionally over the range which separated their station from the watershed of the coastal rivers. Fired with the spirit of exploration, they had resolved to penetrate by sea to the territory they had partially invaded by land. Arriving at Brisbane from a visit to Sydney full of this purpose, they learned that Mr. Andrew Petrie, overseer of works at the settlement, was at that very time under orders to proceed in precisely the same direction. Mr. Petrie very willingly agreed to avail himself of the co-operation of the Russells, and on May 4th, 1842, the combined party started up the coast in an open boat.

Mr. Petrie had arrived in Sydney as far back as the year 1835 as an

assistant to Colonel Barney, and about 1839 he removed to Brisbane. His arrival is

noteworthy on account of the vessel which conveyed him —the "James Watt"

having been the first steamship which entered Moreton Bay. One feature, if not the

principal one, in the instructions upon which Mr. Petrie was now acting was that he was

required to communicate, if possible, with certain runaway convicts who were alleged to be

living with the native tribes to the northward. About halfway between Moreton Bay and the

entrance to Wide Bay, at a cape forming the headland of the southern entrance to the Noosa

lakes, a landing was effected with the assistance of a mob of blacks. Mr. Petrie was the

first to reach the shore, trusting himself, with astonishing hardihood, on the shoulders

of a savage who had, with others, rushed into the water to meet the boat. The conduct of

the blacks was insolent and menacing. Mr. Petrie’s bearer had no sooner deposited him

on dry land that he snatched at his blanket. The sturdy Scotchman had already been

impressed by the demeanour of the blacks, and had begun to suspect that this might be the

place where, and these the savages by whom, a number of shipwrecked seamen had not long

before been murdered. Not at all dismayed, he seized his late carrier and wrested the

blanket from him. The fellow, foiled in this attempt, next snatched at a bag of biscuits;

Petrie forcibly recovered it. The affair became critical. The guns had been left in the

boat, but now Mr. Petrie had his rifle fetched, and loaded it, keeping the natives at bay,

and constraining them at the same time to carry the luggage ashore. Keeping two hostages,

including the would-be thief, the adventurers ordered off the rest to their camp, and,

setting a watch, passed the night on land. Learning that one of the absconded convicts was

not far distant, a letter was sent to him, two of the settlement blacks and one of the

local tribe being the messengers. Obedient to the summons appeared Bracefield, the

absconder, whose native name was Wandi. In appearance, he was undistinguishable from his

companions —his adopted aboriginal father, and two of his friends. For a moment the

wanderer was overcome by emotion. Tears choked his utterance, and his own language refused

to come to him. But his first words were of thankfulness at being restored to the

companionship of white men; his next, alas! an anxious inquiry whether at the settlement

punishment awaited him. The unhappy wretch feared the lash or the rope. Happily, Petrie

had authority to give him gracious assurance. He told Bracefield how the settlement was

altered, how the days of chains and flogging were past, and freedom reigned. Thus relieved

from anxiety, Bracefield entered the camp, and his first remark there must have opened

Petrie’s eyes to the full extent of his rashness when landing. "I suppose,

sir," he said, "you are not aware that the black you have got with you is the

murderer of several white men."  The black indicated was the fellow

upon whose shoulders Petrie had ridden ashore. The latter started, and wheeled round to

shoot the murderer; but he had observed the conversation, and was already darting into the

bush. Taking Bracefield with them, the explorers set sail again, and were the first

voyagers to brave those breakers of Wide Bay bar which have so often proved a trouble to

subsequent mariners.

The black indicated was the fellow

upon whose shoulders Petrie had ridden ashore. The latter started, and wheeled round to

shoot the murderer; but he had observed the conversation, and was already darting into the

bush. Taking Bracefield with them, the explorers set sail again, and were the first

voyagers to brave those breakers of Wide Bay bar which have so often proved a trouble to

subsequent mariners.

Great Sandy Island, so named by Flinders, had, when Petrie and Russell landed upon it, already undergone a change of name to Frazer’s Island. But a short time previously a vessel the "Stirling Castle" —had been wrecked upon its seaward side. The captain (Frazer), his wife, and most of the crew, if not all, escaped from the waves only to meet with a fate worse than drowning. The natives fell upon them, slew them, and probably ate them, reserving the unhappy woman for the gratification of other appetites. She remained for, it is said, eighteen months the slave and bondswoman of these savages, degraded by them beneath even the level of their own females. Intelligence of her existence at last penetrated to the settlement, and a boat party was despatched to endeavour to rescue her. This was successfully accomplished, the woman being assisted to escape by a convict absconder named Graham, who had been for twelve years living with the blacks. The exact particulars of the incident, however, have not been preserved to us.

FROM the high land on Frazer’s Island the Wide Bay River, now called the Mary, was plainly seen and its course distinguished. On the following day it was entered, and for the first time bore on its bosom a European boat and crew. In three days about fifty miles were voyaged to a point where the navigation was obstructed by rocks and shingly beds. Ere long a great gathering of natives was perceived in the neighbourhood. These proved to be very hostile and excited. After some manoeuvring, and at the peril of their lives, Bracefield and one of the Moreton Bay blacks who were with the expedition managed to get among the "myalls," as wild blacks are called in Queensland parlance. Two convict members of Petrie’s crew went forward with Bracefield and the blacks a certain distance, the object being to secure, if possible, one Davis, another absconder from the settlement, who was believed to be certainly with this tribe. So perilous was the adventure considered that these convicts were preferred for it, on the understanding that if Davis was successfully secured they should be rewarded by some improvement of their condition. When the wild white man and the tame black stole in upon the savages, and had fairly got among them, and, the former being recognised, had been received without clubbing or spearing their two white attendants were detected at a distance, and an instant move was made to spear them. But Bracefield had by this time communicated with Davis, or Durramboi, and the two white savages prevailed on their black brothers to spare the trembling convicts. Davis, however, set off running, and surrendered himself to the pair, followed by Bracefield. A singular scene was now enacted by the brace of absconders, who seemed alternately swayed by their original training and their savage habits, and scarcely conscious in which condition they existed. Davis (Durramboi) furiously accused Bracefield (Wandi) of having led the officers to capture him with a view to procure a mitigation of his own sentence. He would credit none of Wandi’s protestations till the latter, moved to rage, became all blackfellow again, and passionately sang a war-song at Durramboi. Thereupon Davis dashed off to the main body of whites. "I shall never," wrote Mr. Petrie in his journal, "forget his appearance when he arrived at our camp –a white man in a state of nudity, and actually a wild man of the woods; - his eyes wild, and unable to rest a moment on any one object. He had quite the same manner and gestures that the wildest blacks have got. He could not speak his ‘mither’s tongue,’ as he called it. He could not even pronounce English for some time, and when he did attempt it, all he could say was a few words, and these often misapplied, breaking off abruptly in the middle of a sentence with the black gibberish, which he spoke very fluently. During the whole of our conversation his eyes and manner were completely wild, looking at us as if he had never seen a white man before. In fact, he told us he had nearly forgotten all about the society of white men, and had forgotten all about his friends and relations for years past, and had I or someone else not brought him from among these savages he would never have left them."

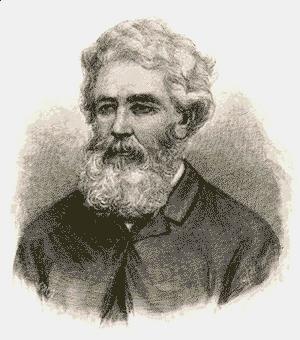

No equally graphic description of a wild white man exists. James Davis, otherwise Durramboi, still lives in Brisbane, where he his for years kept a small crockery shop. Of late, however, he has become habitually reticent, and refuses to talk about the past. Although only sixty-four years of age —he was born in 1824, his father being a blacksmith in the Old Wynd, Glasgow —he looks fully ten years older, the sufferings and hardships of his early life being doubtless accountable for the apparent decay of his strength.

Fortunately it has not been left for the historian of to-day to extract from Davis the story of his strange and interesting experiences. Mr. Stuart Russell held long conversations with him at the time of his rescue, and readily communicates his reminiscences to an appreciative listener. Dr. Lang also fell in with Davis in the year 1845 at Captain Griffin’s station on the Pine River, one of the minor streams which fall into Moreton Bay, and extracted from him copious information.

EARLY EXPERIENCES WITH THE BLACKS.

IT will be convenient to make Davis’ experiences a peg upon which to hang an account of the relations between the pioneers of Queensland and the aboriginal inhabitants. The condition of excitement and murderous hostility in which Messrs. Petrie and Russell found the natives among whom Durramboi was living was due to a recent shameful catastrophe. At Kilcoy Station, on the upper Brisbane, there had just occurred a wholesale slaughter of natives —men, women and children —by poisoning. The news had spread among the tribes, and a furious desire for revenge had possession of them. Mr. Russell recounts how Davis told the story, illustrating it with pantomimic representations of the writhings and convulsions of the victims, as the arsenic, which had been mixed with flour and treacherously given to the blacks, consumed their vitals. Mr. Russell strongly insists that the deed was perpetrated by two lonely shepherds, on Sir Evan Mackenzie’s run, who had been terrified to desperation by the menacing demeanour of a large mob of blacks who hovered round their hut for days, constantly visiting them to demand rations or whatever struck their fancy, and whom, in sheer terror for their own lives, the shepherds at last disposed of by mixing arsenic, with which they were supplied for dipping sheep affected with scab, with flour that they yielded to the demands of their persecutors. It is at least certain that these two shepherds had been killed in revenge for the poisoning. One of the blacks of Durramboi’s tribe had the watch taken from the corpse of one of these shepherds, and surrendered it to Mr. Petrie; but their fate furnishes no proof of their guilt. The natives habitually regard white men as being members of one tribe, and mutually responsible for each other’s acts in accordance with their own customs; hence, innocent white men were perpetually being unexpectedly attacked and killed in vengeance for wrongs that had been perpetrated on the natives, in which wrongs they had no participation, and of which they had no knowledge.

But evidence given to a select committee of the first Queensland parliament with respect to the treatment of the blacks generally seems conclusive that the deed was done at the head station itself, at a time, however, when Sir Evan was absent. A fierce controversy raged respecting the matter for years. The Rev. Mr. Schmidt, one of Dr. Lang’s missionaries at German Station, heard the story from the blacks when visiting the Bunya country, and embodied the narrative in his journal, which was submitted to Dr. Lang, who placed it before the then governor, Sir George Gipps. When Sir George returned the letter to Dr. Lang, the passage relating to the affair was underscored in red ink —a very appropriate colour, Dr. Lang remarks, for an affair of blood. With the view of compelling the governor to take action in the matter, Dr. Lang immediately published the journal. It is possible that there was some necessity for this strong measure. Dr. Lang affirms that Sir George Gipps had himself previously heard the story in Brisbane town, where it was a matter of common conversation, and that his Excellency had merely remarked, pettishly, that it was "got up to annoy him." This apparent reluctance on the part of the governor to move in the affair is perhaps attributable to the character of the presumed criminals. The earliest pastoral pioneers of the Darling Downs and Moreton Bay districts were almost uniformly men of an exceptional order. They belonged to the same rank in society as Sir George Gipps himself, and some, at any rate, were, when visiting Sydney, on a footing of intimacy with him. Several of these were ex-officers of the army and navy. Dr. Leichhardt had been surprised, when he first visited Moreton Bay in 1843, to find, as he travelled from station to station in that frontier region —the most remote on the world’s surface from the centres of civilisation —his successive hosts to be gentlemen of breeding and culture, who had even travelled on the continent of Europe —the grand tour which, after the fall of Napoleon, was considered essential to impart polish to young men of family. The contrast between the situation and the persons struck him sufficiently to occasion a remark in one of his letters written on the spot. "The settlers," he wrote, "have treated me very kindly. Mr. Archer, Mr. (Sir Evan) Mackenzie, and Mr. Biggs are all well-educated men. It is remarkable how many of these settlers have travelled in Germany." In addition to the three mentioned in this passage, others, among many may be named. Mr. (now Sir Arthur) Hodgson, who had been first to follow Patrick Leslie on the Darling Downs, had been educated at Eton; the brothers Russell were gentlemen; Mr. McConnell had come to Australia with considerable property. The slaughter of a native was, on conviction, a hanging matter, and Sir George was naturally indisposed, in the absence of satisfactory evidence, to stir up prosecutions against gentlemen of culture whom he believed to be incapable of the crime of poisoning.

The historian who has ransacked the repertoires of official records, and has sought information from the survivors among the early pioneers and colonists, cannot but admit that poisoning was a common resource in dealing with the wild blacks. The universal use of arsenic for sheep-dipping placed the means within the reach of all who chose to use it. Generally, it was the isolated shepherd or stockman who thus relieved himself of menacing enemies as treacherous as himself. But such tragedies were generally insusceptible of proof. They formed the text of yarns round the camp fire and in the shearers’ hut, just as, within the recollection of men not now past middle age, in northern Queensland, exciting accounts of battles of blackfellows were as common as sporting narratives of riding down dingoes or emus and bringing them to earth with a blow from a stirrup-iron swung at the end of the stirrup-leather, detached for the purpose, while the rider dashed along at a gallop. On the frontiers everybody knew all about it, but a certain reserve was maintained in general conversation. Names were omitted, and localities merely shadowed. Some squatters stood out against the prevailing influence, and did their best to keep on kindly terms with the natives about. Some encouraged and protected them, and permitted them to "come in" to the head station. This was generally condemned as unwise, and even foolhardy, and several tragedies —that at Hornet Bank, elsewhere referred to, and the wholesale slaughter of the Wills family on the Barcoo many years later —supported that view. Others, again, would not permit the blacks to approach the head station, but, warned them off, while strictly prohibiting the "jackaroos" and station hands from molesting them in the bush. "Jackaroo" is a nickname, understood to be fraught with some contempt, bestowed by the working hands upon the young men who, mostly arrivals from Great Britain, lived with the squatter, and learned bushcraft preparatory to themselves becoming squatters.

It was very difficult for even the best intentional run-owner to abide

by his humanitarian maxims. His shepherds were murdered because a neighbour, perhaps one

hundred miles distant, and on the other side of an impenetrable range or scrub, had raided

a black’s camp, or because a party along with travelling stock had carried off a

"gin," as native women are called, and shot her mate. Cause and effect were not

distinguishable.  When he had believed himself to have deserved his

blacks’ goodwill, his cattle were speared and his flocks raided. Again, a neighbour

arriving to pass the night would recognise in Jacky, the host’s favourite and model

black, camped with the tribe in the homestead paddock, or chopping wood for the cool, the

ringleader of an attack upon the neighbour’s out-station, and the murderer, it may

be, of his overseer. Jacky’s fate would be sealed, and it would be impossible for the

humanitarian squatter to remove from the minds of the tribe the impression that he had at

least a consenting part in the shooting, although it might not occur for weeks after, and

right away out on the run. The other blacks would know who fired the shot, and would

recall the significant and impassioned looks and conversation when the visitor had pointed

out to the host what manner of blackfellow it was that he was harbouring. Then, when the

native police grew into an institution, all humanitarianism became impossible. Tame blacks

from the earlier settled districts were supplied with uniforms, firearms, and horses, and

placed under the direction of a lieutenant whom they feared as they did "Debbil

Debbil and affectionately addressed as "Maamie" —with perhaps a white

sergeant besides. Their troop patrolled the frontier districts, and woe betide the tribe

on whose tracks their sharp eyes alighted. At the summons of the squatter who found the

blacks trouble some, the black troopers put in a speedy appearance, and undertook the

"dispersal" of the nuisances. "What do you mean by ‘dispersing’

the blacks?" was the query put to a native police lieutenant by a member of a

parliamentary commission in Queensland. " Firing at them," was the laconic

reply. Such frankness was, however, singular and exceptional. The realities of the system

were almost uniformly veiled under mild euphemisms which everyone understood.

When he had believed himself to have deserved his

blacks’ goodwill, his cattle were speared and his flocks raided. Again, a neighbour

arriving to pass the night would recognise in Jacky, the host’s favourite and model

black, camped with the tribe in the homestead paddock, or chopping wood for the cool, the

ringleader of an attack upon the neighbour’s out-station, and the murderer, it may

be, of his overseer. Jacky’s fate would be sealed, and it would be impossible for the

humanitarian squatter to remove from the minds of the tribe the impression that he had at

least a consenting part in the shooting, although it might not occur for weeks after, and

right away out on the run. The other blacks would know who fired the shot, and would

recall the significant and impassioned looks and conversation when the visitor had pointed

out to the host what manner of blackfellow it was that he was harbouring. Then, when the

native police grew into an institution, all humanitarianism became impossible. Tame blacks

from the earlier settled districts were supplied with uniforms, firearms, and horses, and

placed under the direction of a lieutenant whom they feared as they did "Debbil

Debbil and affectionately addressed as "Maamie" —with perhaps a white

sergeant besides. Their troop patrolled the frontier districts, and woe betide the tribe

on whose tracks their sharp eyes alighted. At the summons of the squatter who found the

blacks trouble some, the black troopers put in a speedy appearance, and undertook the

"dispersal" of the nuisances. "What do you mean by ‘dispersing’

the blacks?" was the query put to a native police lieutenant by a member of a

parliamentary commission in Queensland. " Firing at them," was the laconic

reply. Such frankness was, however, singular and exceptional. The realities of the system

were almost uniformly veiled under mild euphemisms which everyone understood.

DURRAMBOI’S STORY.

To return to Davis, or Durramboi. When he absconded from the penal

settlement in Brisbane, preferring all hazards to the terrors of Logan’s merciless

rule, he had with him a mate. The absconders soon fell in with a numerous tribe of

aborigines, by whom they were kindly and hospitably entertained. Davis’ companion,

however, perished ere long, killed in expiation of an accidental sacrilege he committed in

the emptying of a parcel of bones from a native basket which he found in a tree, and which

he appropriated to carry oysters in. The bones were the mortal remains of deceased

blackfellows. Such another basketful was shewn on Frazer’s Island to Petrie when he

was endeavouring to recover the bones of Captain Frazer and his crew, which were preserved

in the neighbourhood, but which, being pressed for time, he could not wait to obtain.

Davis probably owed his prolonged immunity to a superstition apparently universal among

the aborigines of the East Coast. They had observed that the white men with whom they fell

in from time to time almost invariably made their appearance from the ocean, on the

horizon of which the sun rose. They conceived that the wonderful strangers were other than

ordinary mortals, and vaguely conjectured that they were deceased blackfellows returned

from the sun or the sea. This conception may be traced and attributed to a curious custom

practised in dealing with such of their warriors as fell in battle, and sometimes

apparently with individuals who died under different circumstances. These natives are

cannibals the evidence in this regard is overwhelming. Davis, Bracefield, Pamphlet,

Finnegan, Morill, and other whites who have lived among the blacks, concur in this

testimony; and numbers of settlers have been able to corroborate them in some details.

When a native was slain in battle, his friends carried off the corpse, and ate it. They

believed that they discharged a duty, did honour to the deceased, and benefited themselves

by the act.  They not only incorporated his substance with their own, but gained

participation in the courage and good qualities which had distinguished their friend.

Ordinarily they did not eat their dead enemies, but there seem to have been exceptions.

They appear to have had a relish for human flesh independent of rites. After the

abandonment of the first settlement in Moreton Bay and the removal of the establishment to

Brisbane, the German missionaries detached one of their lay brethren, Mr. Haussmann, to

the deserted station at Humpy Bong. There he was attacked in his hut, severely wounded

with spears, and barely escaped with his life into the bush. While some were attacking the

hut, others were lighting a fire, and Mr. Haussmann, who understood their language, heard

them remark that "he was fat, and would eat well." Women are also eaten. Mothers

devoured their dead children, carrying their bones thereafter for long periods, and, when

moved by affectionate recollections, bringing their relics forth from their dilly-bags and

crying over them. An instance is recorded of a native mother thus carrying about with her

all the bones of her child, and in emotional moods producing them, and reconstructing the

entire skeleton, with an expertness which an experienced osteologist might envy, to weep

and lament over the remains.

They not only incorporated his substance with their own, but gained

participation in the courage and good qualities which had distinguished their friend.

Ordinarily they did not eat their dead enemies, but there seem to have been exceptions.

They appear to have had a relish for human flesh independent of rites. After the

abandonment of the first settlement in Moreton Bay and the removal of the establishment to

Brisbane, the German missionaries detached one of their lay brethren, Mr. Haussmann, to

the deserted station at Humpy Bong. There he was attacked in his hut, severely wounded

with spears, and barely escaped with his life into the bush. While some were attacking the

hut, others were lighting a fire, and Mr. Haussmann, who understood their language, heard

them remark that "he was fat, and would eat well." Women are also eaten. Mothers

devoured their dead children, carrying their bones thereafter for long periods, and, when

moved by affectionate recollections, bringing their relics forth from their dilly-bags and

crying over them. An instance is recorded of a native mother thus carrying about with her

all the bones of her child, and in emotional moods producing them, and reconstructing the

entire skeleton, with an expertness which an experienced osteologist might envy, to weep

and lament over the remains.

One of the first processes in preparing the corpse for consumption is to scorch or singe the body all over. The epidermis, or outer skin, is then scraped off, together with the membrane containing the colouring pigment of the skin, with sharp shells, or even with the fingernails. After this treatment the corpse is perfectly white. Upon the remaining treatments we need not dwell. It will suffice to state that the true skin or hide is dried over fires and preserved for indefinite periods, being used as a potent charm against sickness when placed over the sufferer. But it is this white stage which, in the imagination of the natives, identified Europeans with the dead. The companions and friends of a certain deceased native fancied that they recognised Davis as a reincarnation of a late lamented whose name had been Durramboi. Davis was adopted by Durramboi’s bereaved parents, and was safe from that moment. Once or twice, when his ignorance of their modes of thought betrayed him into a violation of some sacred observance, suspicions as to his identity with Durramboi were excited. He was accused of being "Mawgoory," which seems to have signified a ghost, a spectre, an evil spirit; and as it seemed that the natives perceived no incongruity in the idea of killing a ghost, Davis was momentarily in serious peril. Passing from tribe to tribe, the runaway travelled far to the northward, and was always entertained as a blackfellow returned from the dead. But, somewhat inconveniently, fresh recognitions awaited him with different tribes. He was Durramboi in Wide Bay, but he had to accept the personality of someone else when he joined another tribe; and occasionally his inability to recognise friends who had been intimate with him before he died gave rise to awkward misgivings among these individuals. But it sometimes happened that no identification took place. He was a blackfellow returned from the great hereafter —admitted; but what blackfellow? On such occasions Davis had an answer pat. It was, he explained, so very long since he died that he had forgotten what his name had been prior to that event.

Davis’ frequent journeys enabled him to give much valuable information with respect to those northern tracts which he alone among white men had traversed, and as to the existence of numerous rivers, some of great size, which must have been useful and encouraging to the subsequent pastoral pioneers. click here to return to main page