Die Natursymphonie

(The Nature Symphony)

“Since his youth, mountains had been

the element in which my father could renew his strength.” Friedrich von Hausegger also said that his father’s happiest hours were

with his family and friends in their summer home at Obergrainau.

Karl Straube wrote to him:

“In every inner and outer respect,

you belong to

need the

rarefied air of its towering mountain peaks.”

It seems

a given that the powerful impressions of the solitude of the mountain peaks (Hochgebirgeinsamkeit,

Hausegger called it) would inspire his greatest and

most ambitious work. He completed the Natursymphonie in Sept. of 1911, but didn’t name the work

till after its premier. He wrote:

“It was only with great difficulty that I resolved to

call the work Die Natursymphonie…

I hoped the expression Natur, combined with the motto on the score and the words of

Goethe’s Proömion which are the basis of the final chorus

might serve as a guide to the listener.”

An

unusual comment from a composer whose every work has a

title. Concerned that words might trivialize the music, he pointed out that he

didn’t mean “Nature” to invoke a specific landscape a la Mendelssohn’s

“Von Gebirg zum Gebirg “From mountain peak to peak hovers the

schwebet der ewige Geist, eternal spirit, prescient of eternal life”

ewigen Lebens ahndevoll”

The

choral finale also sets a Goethe text, the first half of his Proömion; a word

difficult to translate, except as “Proem” or “Prelude”.

In Namen dessen

der Sich selbst In

the name of Him who caused Himself

erschuf ! to be

Von Ewigkeit in schaffendem Beruf; Creating

ever from eternity

In Seinem Namen der

den Glauben In His Name, who made faith and trust

schafft; and

love

Vertrauen, Liebe, Thätigkeit

und Kraft The

strength of things and man’s activity

In Jenes Namen, der,

so oft gennant In

That One’s Name, Who named though

Dem Wesem nach blieb

immer of He be

unbekannt Whose

Essence yet remains a mystery

So weit das Ohr, so weit das Auge So far as hearing holds, so far

as

reicht sight

Du findest nur Bekanntes

das Ihm Thou

findest only known shapes like

gleicht to

His

Und deines Geistes höchster And soon thy spirit’s highest fiery

Feuerflug flight

Hat schon ein Glechnis,

hat am Hath store

enough of symbols,

Bild genug likenesses

Es zieht dich an, es reißt dich

Thou art drawn

onward, sped forth

heiter fort joyously

Und wo du wandelst

schmückt sich And where thou wanderest,

path

Weg und

Ort and

place grow bright

Du zählst nicht mehr,

berechnest No

more thou reckonest, time’s no

keine Zeit more

for thee

Und jeder Schritt ist Unermeßlichkeit And every footstep is Infinity

Die Natursymphonie is in three

movements, the first two played without a break, and lasts about an hour. Leuckart published the music in 1912. To realize his

concept, Hausegger used his largest and most colorful

orchestra:

piccolo,

2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, D

clarinet, 2 A or Bb clarinets, bass clarinet

3 bassoons (contrabassoon)

6 horns,

D trumpet, 3 C trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba

2 tympanists, 4 percussion- bass drum, snare drum, large tenor

drum, crash and

suspended cymbals, triangle, gong, glockenspiel and

xylophone

2 harps,

celeste, organ, (62) strings, chorus in as many as 11

parts.

The general plan of the first

movement is a slow introduction, followed by a faster main body, with a calm

interlude at its center. The music opens with a solo horn call, expanded by the

trumpets.

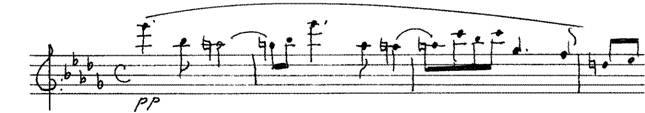

Ex. 1

Phrases a and b become much more weighty as the work

progresses. Ex. 1b is the Nature Theme which will pervade the piece like the

motto theme in Elgar’s First Symphony and unite the entire work. Note its “imperfect” intervals; that of the tritone

is an especially important detail. We next hear an expansion of that

theme on the organ pedal.

Ex. 2

The

bassoon continues the theme and the music moves into D flat major, the underlying

tonality of the symphony.

Ex. 3

A

repetition of the horn summons, Ex. 1, impels the music to a faster pace. An

urgent tremolo figure in the basses gets taken up canonically through the

strings. The Nature Motiv reappears on the horns and

trumpets, leading to the first allegro theme, on the high woodwinds.

Ex. 4

There’s

also a brief figure first heard on the D trumpet, then the horns, patently

related to Ex. 1

Ex. 5

Soon,

the actual main theme of the allegro emerges on the flutes, its initial phrase

incorporating Ex. 1

Ex. 6

An

extension of the string entry to Ex, 6 also forms an

important element:

Ex. 7

The

pulse slows and a bassoon theme

Ex. 8

leads

to a more pastoral segment.

Ex. 9

The

music uses interchanges of Exx. 8 and 9, as well as a

further variant of Ex. 4

Ex. 10

A more

impelling theme, derived from Ex. 7, combines with the bassoon motiv

Ex. 11

Now arrives

the calm at the heart of the turmoil. Divisi strings

play a beautifully harmonized orchestral song in B major (but note the errant

bass clarinet).

Ex. 12

Hausegger sustains this lyric output, with an especially appealing

continuation on the violins, including a descending thread which will blossom

later.

Ex. 13

Yet, at the

same time, there’s a more somber call on the bassoons (note portion x)

Ex. 14

Towards

the end of this section, we hear a woodwind chord progression which will return

with greater impact:

Ex. 15

The

allegro music resumes with Ex. 6 in the bass in C minor. The winds take it up

into E minor, interspersed with Ex. 8 and phrases of Ex. 3 churned about.

Although the momentum continues,

impelled by Ex. 7, the character of the music becomes less an allegro and more

grandiose in feeling. Now a crescendo is taken up with this sequential - and consequential - trumpet phrase:

Ex. 16

The

music builds to a peak, topped by an augmented brass version of the bassoon

theme, Ex. 13. we are now at the climax of the

movement. In a broadly paced, luminescent E major, a bed of pulsing triplet

chords, divisi strings and upwardly heaving bass

glissandi bears this long violin theme (Ex. 17):

Ex. 17

The

feeling of triumph subsides. Two oboes play a plaintive echo of Ex. 13. The

strings play a sequence of icy tremolos (mostly 6/3 minor triads) and this

organ progression forms the bridge to the second movement.

Ex. 18

The center movement, a huge

orchestral nocturne, has two elaborate (and one brief) sections. Like the

middle movement of Barbarossa, the last

portion is a contracted version of the first. Over quiet tympani pulsations, it

begins with a wide-ranging bassoon solo; in Hausegger’s

words “a death-cry of Nature”.

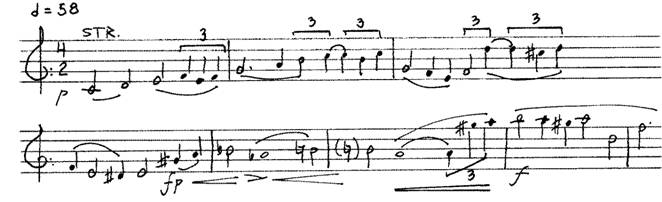

Ex. 19

Clarinets

and the English horn (including a glissando for the latter) take up variants of

Ex. 18b. A further extension of Ex. 18a continues the movement. Each phrase

seems a transformation of the last, in a developing variation.

Ex. 20

The

movement broadens out into an orchestral song. At its climax, the orchestra sounds

a theme whose extension will be the focus of the second part of the movement:

Ex. 21

As the

climax dissipates, a solo violin introduces a calmer section in D flat major,

with a feint toward E flat minor.

Ex. 22

A solo

flute picks up the song

Ex. 23

leading

to a wonderful interlude of repose. I can’t help relating this whole section to

the words of Hausegger’s son:

“One spring day…I wandered above Obergrainau…His favorite flowers-

gentians

and primroses - were in bloom, yet the wintry snow lay atop the

mountains.

By accident, I came upon the large stone upon which he’d lay

his

scores…to ‘walk his thoughts’ as he put it, so he could work in complete

solitude.

Here was his world.”

The celeste and divisi violins play a

chordal theme.

Ex. 24

Hausegger works these elements into an expansively songful

segment, completed by a gentle call of the Nature theme on the brass. This

version will assume more weight in the finale:

Ex. 25

After a

last reminiscence of Ex. 23, the second major section of the movement begins. A

somber procession in the Phrygian mode on C#, Hausegger

wrote that its inspiration was the legend of the passage of the souls of the

dead over the Aletsch Glacier into the afterlife.

Over a tympani ostinato, the horn fragment heard in

Ex. 20 is now fleshed out - if one can say that about a theme harmonized in fifths

(Exx. 26 and 27).

Ex. 26

Ex. 27

Underpinned

by the relentless tympani, the procession gathers strength till we hear Ex. 18b

ff on the winds and lower brass. By

now, the entire orchestra stresses the upbeat of the tympani rhythm and the

organ sul pleno adds its weight to a peak of crushing power.

In an elegiacally

extended Abgesang,

the horns and bassoons resume the cortège of Ex. 25, and the clarinets in

thirds sound Ex. 18b. To the accompaniment of throbbing, syncopated viola

triplets, the violins spin out a long extension of the Nature Motiv:

Ex. 28

With a

final sounding of the Nature theme on the organ pedal, the movement settles to

its fundamental C# tonal center (enharmonic equivalent of the work’s basic D

flat tonality).

The first section of the final

movement is a free rondo, beginning with a stormy allegro theme. Both the theme

itself and the interjecting woodwind figure include the Nature Motiv in diminution:

Ex. 29

The

turbulent rhythms soon lead to one of the most important themes in the

movement, resounding on the trumpet over the melee, its soaring contours making

a vivid contrast with the opening gesture:

Ex. 30

A

variant of Ex.15 from the first movement and the high woodwinds again top the

textures with the Nature Motiv.

The first figure (Ex. 27) reappears,

again in E minor, this time more fully scored and vehement. Driven by

overlapping repetitions and chattering fragments of Ex. 8 and the woodwind

interjection from Ex. 27a, the momentum subsides in disjointed phrases. These

coalesce into a lyric theme in B major, its lineage traceable to Exx. 7 and 11.

Ex. 31

The

constant emphases on the leading tone give the melody a yearning quality. Hausegger works this long tune into a more

optimistic-sounding segment which, after a veiled reference to the Nature

theme, is cut off by the reappearance of the initial gesture (Ex. 27) of the

movement. The tension builds, using rushing chromatic moanings

in the lower strings. Fragments of Exx.

27 and 29 toss about in the turmoil, building via the chromatic trumpet theme

from the first movement, Ex. 15.

When the tension ramps up to its

peak, the orchestra stops on a fff unison C and

the chorus enters, at first a cappella, to the words of Proömion (again, note the tritone).

Ex. 32

The

syllable schuf

is accompanied by an upward sweep through the strings and woodwinds, tipped by

a piccolo flourish. Even this figure is thematic, derived from the Nature theme:

Ex.

33

At the

second repetition of der dich selbst erschuf (who caused himself to be),

Ex. 30 again calls out triumphantly in proud augmentation on the trumpet, mirroring

this concept. Ex. 31 reappears, now in the basic D flat major tonality, as a

brief interlude. At the words “In his name, who made faith…” a noble new theme

appears, in Rudolf Siegel’s words “a solemn song of peace”.

Ex. 34

The

meaning of the organ progression, Ex. 18, now becomes clearer, as it

accompanies the words “oft-named and yet unfathomable mystery”. Again, the

organ intones the Nature Motiv.

At the words “Far as thy hearing

holds, far as thy sight…” a small choir sings an E major fugato variant of the

Nature theme. This music is couched in a pious, hymn-like idiom. The full choir

joins in, with the voices now in as many as 11 parts, some of them further

variations on the Nature theme. (This patch, though brief, is a stiff

assignment for the singers, with seriously gnarled chromatic lines which, even

with instrumental support, are no easy task. The WDR Rundfunkchor

on the cpo recording deserves

laurels for its highly competent handling of a thorny mission.)

The emotional climate grows more

urgent. Ex. 31 now recurs in E major, supporting the

words “hath store enough of symbols, likenesses”. At the phrase “where thou wanderest, path and place grow bright”, a new version of

Ex. 30 appears.

Ex. 35

The

music steadily builds over a ground base formed from the first two bars of Ex.

35. Along the way, the music picks up Ex. 32 on the trumpets. Reflecting the

words “And every footstep is Infinity”, with the full power of von Hausegger’s greatest orchestra and chorus, the music

achieves a stunning climax, pausing on a B flat minor chord (relative minor to

the main tonality).

A pp choral progression, accompanied by the organ and Ex. 33 in the

strings leads to the most exalted moment in this masterpiece, when the Natur Motiv is transformed into a

serene hymn of redemption:

Ex. 36

The

final repetition of Unermeßlichkeit (Infinity) brings the huge

orchestral/choral apparatus to a peak on a D flat major chord. With one last

detour towards A major, the return to its home D flat

crowns this transcendental symphony.

Ex. 37

Die

Natursymphonie was, from the outset, recognized as von Hausegger’s finest achievement and the passage of nearly a

century hasn’t changed that judgment. Eugen Jochum conducted it several times before WW II and always

regarded it as a significant work.

The symphony displays the composer’s

mastery of every phase of his art, from formal control to orchestral

virtuosity. The constant presence of the Nature Motiv

and the variously subtle ways it pervades so much of the other thematic

material creates, in retrospect, an unusual sense of overall integration,

despite the length of the work. Music-lovers who have recently embraced not

only Mahler, but the works of Korngold, Schreker, Zemlinsky and other Austro-German Post-Romantics will

welcome this sonic blockbuster.

Luckily, there’s a superior

performance available on cpo

(SACD 777 237-2), with Ari Rasilainen conducting the

WDR Orchestra and Chorus of Cologne. The playing is solid and assured, with

none of the hesitancy one sometimes hears with unfamiliar repertoire and the

choral work, as mentioned earlier, is excellent. Rasilainen’s

sympathetic interpretation is all the more admirable as he has no models to

build on - so far as I can determine, the work hasn’t been played since before

WW II. Let’s hope that, with the chance to hear von Hausegger

at his best, this changes.