|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| landlords to pay more money to support his own troops as well as social projects to improve the lives of the peasants and so earn their support. Naturally, the landlords resented this and the generals of the National Army of Vietnam, which the French had allowed to be formed, were embarrassed by the fact that Colonel Leroy, with about 3,240 troops, was accomplishing more than they were with 5,840 troops. After earning too many enemies in high places with his success, Leroy was promoted or kicked up-stairs and his Catholic brigades were disbanded in 1952. The area was handed over to Vietnamese National Army forces which soon proved totally incapable of keeping the province free of Communist activity. Colonel Leroy went on to fight as a counter-terrorism officer in Algeria on orders from President DeGaulle. |

|

|

|

The National Army of Vietnam was a recent innovation, set up after the French decided to sponsor their own anti-Communist government in South Vietnam in the hope of drawing support away from the Communists. Going back to the proposal of Admiral d'Argenlieu, the French had brought back the former Emperor Bao Dai to head the new government. However, it was not a full restoration of the monarchy. This was not to be the Nguyen Empire, but the State of Vietnam with Bao Dai holding the title of Chief of State rather than Emperor. The short-lived Republic of Cochinchina was also necessarily included in the new State. However, the officials who ran the government proved unpopular and ineffective and Bao Dai himself won few friends by staying in France, gambling in Monaco, partying in nightclubs and sampling the favors of French courtesans. The nations of the Free World lined up in recognition of the State of Vietnam as the legitimate government while the nations of the Communist bloc supported the government of Ho Chi Minh. The war would have to decide which one was to prevail. It could not have been a good omen when the first Prime Minister of the State of Vietnam, General Nguyen Van Xuan, predicted its ultimate failure. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

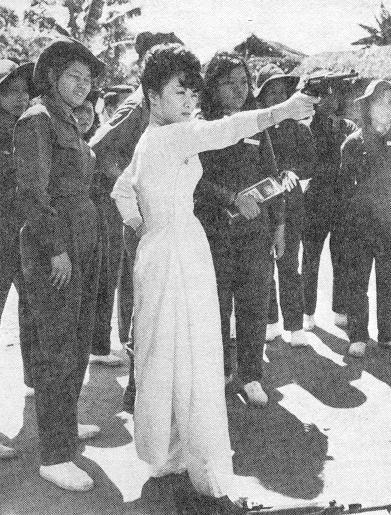

Catholic militia troops |

|

|

|

|

|

| Many Catholics opposed the new government, just as they opposed that in the north as the Communists asserted ever greater control. One area that was particularly unique was the dioceses of Phat Diem and Bui Chu. In the late 1800's a Vietnamese priest, Father Tran Van Luc, had been given a title along the lines of a baron over the area from ThamHoa to Phat Diem which had a sizeable population of Catholics. The men who came after him, such as Bishop Le Huu Tu of Phat Diem and Bishop Pham Ngoc Chi of Bui Chu became prince-bishops who held temporal as well as spiritual authority over the area; an area which, by 1945, included roughly 800,000 Roman Catholics. The bishops levied taxes, maintained a militia and managed their normal duties of offering the sacraments of the Church. The villages each contained a fortified parish church and the local priest managed local government and defense for his parish along with his spiritual obligations. |

|

|

| In the past, this region of Annam had suffered greatly for supporting the French when they first arrived to protect the Catholic community. As a result, they were harshly persecuted and so were very reluctant to be seen as allies of the French after World War II when they returned to reestablish their authority. Because of this, Bishop Taddeo Le HuuTu at first cooperated with the government of Ho Chi Minh, which not everyone knew was Communist in the early days. Much like Emperor Bao Dai he was also named "Supreme Advisor" to Ho Chi Minh. However, once he saw that the Communists were in control of the government and slowly eliminating all opposition he left and returned to his diocese. He organized his own mini-army and had factories for making munitions, his own arsenals and a radio station to keep in constant contact with the Vatican. When he was obliged to call in the French for military assistance in late 1949 he agreed to recognize the government of Bao Dai, before which time the region had been both anti-French and anti-Communist. The hard pressed French soon withdrew to other areas though, leaving the Bishop as master of his own domain and responsible for his own defense once again. |

|

|

|

| Two years later the Communist VietMinh launched a major offensive in the region which proved too much for the Catholic militia and the French commander in Vietnam, General de Lattre, abolished the special privileges of the bishops and put the area under permanent French-Vietnamese occupation. However, they proved unable to keep the VietMinh out and in 1954 the Communists carried out brutal retaliation on the Catholic community for cooperating with the French and their State of Vietnam. Most of the Catholics in northern Annam were forced to flee for their lives to the relative safety of Cochinchina, accompanied by their bishops. Neutrality had proven impossible even though, while the bishops had recognized the regime of Bao Dai, like most groups they never totally submitted to it and had remained autonomous. Even the Catholic League, led by Ngo Dinh Diem, which had at first cooperated with Bao Dai, were careful to keep their distance from him as he was seen by the majority as nothing more than a pleasure minded instrument of France. |

|

|

| Catholic partisans in Annam |

|

|

| Many of the Vietnamese bishops, like Le HuuTu and Pham Ngoc Chi, tried to remain neutral at first, uncomfortable with either of their options; fearing the atheistic rule of the Communists and unable to accept the French regime as being able to protect them. The State of Vietnam under Bao Dai consisted of various independent factions. Along with the French and the Vietnamese Catholics major groups included the criminal Binh Xuyen gang and the Cao Dai and Hoa Hao religious cults. While groups like these could keep the Communists out of their areas, they were all representative of very different beliefs and agendas. As a result, it was impossible to form a national government that could inspire nationwide support and international respect. As the French went down to defeat at Dien Bien Phu in 1954 it looked as though the only thing propping up the government of Bao Dai, who was still safely in his chateaux in France, was about to be gone and nothing would be left to stop the Communists from taking control of Indochina. The United States, which had supported the French government but was never inspired by their Vietnamese allies, decided that something had to be done to stop this Communist threat and the man they looked to as a leader for this "third force" was the Catholic Ngo Dinh Diem. |

|

|

| Ngo Dinh Diem had solid credentials as a public servant. He was known for his honesty, zealousness, conservatism and devotion to Vietnamese independence. He worked his way up as a mandarin and came to court under the guidance of Nguyen HuuBai. He refused to be part of a puppet government and had resigned from the cabinet of Bao Dai and had refused to work with him subsequently. It was a difficult position for Ngo Dinh Diem, whose family had served the Nguyen Dynasty for a long time and who was a devoted monarchist. However, he viewed Bao Dai as unworthy and ineffective. When he finally consented to be Prime Minister of the State of Vietnam under Bao Dai many people noted the stark contrast between the two men dubbed the puritan and the playboy. As much as the former emperor was known for his womanizing and hedonism, Diem was known for his asceticism and devout Catholic faith. He attended mass daily, prayed for two hours a day and spent his free time secluded in monasteries. He had considered taking holy orders but did not, leaving that to his elder brother Ngo DinhThuc who became Archbishop of Hue. |

|

|

| As the Prime Minister, Diem was determined to fulfill the promise he made to the former Emperor to clean up South Vietnamese government and society and he did this even when it meant tearing down those criminal elements Bao Dai had ties with. Ngo Din Diem started by dismissing troublesome officials and practically declaring war on the BinhXuyen gang which ran the gambling houses, opium dens and brothels in Saigon and who sent a percentage to the former Emperor and the French for turning a blind eye to their activities. In a direct provocation Diem held a symbolic mass burning of opium pipes to show his contempt for this racket of sin. It finally came down to violence and in a head to head fight in the streets of Saigon; Diem defeated the Bin Xuyen and their leader Le Van Vien. Similarly, Diem went against the armed cults of the Hoa Hao and Cao Dai. The campaign was successful but these actions also sent pleas to the former Emperor in France who had formerly looked the other way to their actions though most did not support him or the French anyway. Bao Dai then attempted to dismiss Ngo Dinh Diem who, especially after uncovering all of these activities, decided that the nominal position of the former Emperor had to go. |

|

|

|

|

| In 1955 Ngo Dinh Diem held a referendum in which the choice was put to the people to retain the former Emperor in France or to have a republic with Diem as president. After changing camps so many times and being appointed to his position by the French, Bao Dai had practically no support in South Vietnam and Ngo Dinh Diem easily won becoming the first President of the new Republic of Vietnam. It was a difficult step for someone like Diem to take, but he viewed it as the only way and now he was free to put his ideas about government into effect, all of which were influenced by his Catholic morality. As a side note, Emperor Bao Dai eventually calmed down somewhat, married a French woman (who he had always been more fond of anyway) and himself eventually converted to the Catholic faith of his late wife and children, meaning that had things gone differently early on Vietnam might have had a Catholic Emperor today as so many had long hoped for. |

|

|

|

| However, this was not too different from what existed in South Vietnam under President Ngo Dinh Diem. Cut from the old cloth, many commented that Diem behaved more like a monarch than a politician. He instituted many sweeping reforms and programs to encourage patriotism, anti-communism and public morality. With internal corruption still being a problem for the regime in Saigon he was forced to rely heavily on his family, particularly his brother Ngo DinhNhu, head of the Can Lao personalist party and his wife, known as Madame Nhu, who took on the role of unofficial First Lady of South Vietnam. In the Geneva agreement that ended the French war in Vietnam it was decided that after a certain period of time elections would be held throughout North and South Vietnam to determine which government would unite the country. President Diem, wisely, refused to go along with this since Ho Chi Minh had established a Communist dictatorship in the north and had long been sending political agents south and would certainly get 100% of the vote in all the areas he controlled. Communist agents would assassinate village leaders and torture local officials to frighten the peasants into either joining them or at least remaining neutral and not supporting Ngo Dinh Diem. |

|

|

| Because of this, President Diem launched a nationwide campaign in South Vietnam to eliminate the Communist threat. He built up his army and police forces who for a time managed to succeed and all but destroy the Communist presence in the south. However, Ho Chi Minh was not willing to give up on his goal of ruling all of Vietnam and he began to send Communist agents and later Communist weapons and soldiers into South Vietnam where they formed a terrorist organization known as the Viet Cong which had the goal of overthrowing President Diem and making South Vietnam Communist. They carried out terrorist attacks such as bombings and assassinations and threatened to undo all that Diem had accomplished. As a result, the United States, now under her first Catholic President, John F. Kennedy, sent more American aid and military advisors to South Vietnam to assist Ngo Dinh Diem. There was also a massive migration of Vietnamese Catholics escaping from the Communist north and coming south. Whole parish communities were transplanted and these faithful Catholics were to be the most reliable base of support for President Diem and his anti-Communist crusade. |

|

|

|

The support of the Eisenhower administration and later President Kennedy for Ngo Dinh Diem was the beginning of the American War in Vietnam, though the US did not take the lead in the war effort until after Diem was gone. As the Viet Cong stepped up their attacks, Diem launched a comprehensive campaign to elevate Vietnamese society and combat Communism. At home this included the campaign to promote morality which Madame Nhu played a part in and reflected the Catholic principles of the Presidential family. Divorce, contraception and abortion were outlawed, adultery laws were strengthened, beauty contests were banned and dance halls, fighting rings, brothels and opium dens were closed. This campaign of public decency, while undoubtedly good for society, raised opposition from the less desirable elements. The United States also expressed disapproval of the Catholic ruling family in Vietnam, especially Ngo DinhNhu and his wife. President Diem, however, relied on them and would change nothing. He would be the puppet of no foreign power and would not give in to efforts to divide his government and spread internal dissension. |

|

|

|

|

| The Flag of South Vietnam |

|

|

|

|

| For his part, Ngo DinhNhu concentrated on building up a sound political doctrine for the new nation, based on the inherent worth of the human person. He was also largely responsible for combating Communist infiltration and helped develop the idea for the Strategic Hamlet Program. This was an effort to cut the Viet Cong off from their support in the countryside by concentrating the peasants onto heavily fortified hamlets that could be easily defended. Yet, Communist infiltration continued, despite the best efforts of President Diem. They saw in him a real threat and someone with a level of tenacity to equal their own and the Viet Cong made it their number one goal to topple him. Meanwhile, criticism from the international community was growing against Diem who was accused of being too autocratic and intolerant of opposition. These critics either failed to understand or chose to ignore the fractured nature of the country he inherited. Diem had to ensure total unity and show no weakness if he was to defeat the Communists. Ho Chi Minh of course was a dictator who had eliminated all of his opposition in a succession of purges and so he was able to command a North Vietnam totally united by force and intimidation. They were using those same methods in South Vietnam and President Diem had to do whatever was possible to keep the Communists at bay and he was fully prepared to do so regardless of his popularity on the world stage. |

|

|

| This situation came to a peak with the Buddhist crisis in 1963. President Diem had long warned the Buddhists that they needed to do more to regulate their religion since, as it stood, anyone could shave their hair, don a yellow robe and pass as a Buddhist monk. Nothing changed and soon information came about that several Buddhist temples had been infiltrated by Communists. South Vietnamese military units responded to the threat and were faced by a skillful Communist propaganda campaign. Buddhists appeared on American television telling people that they were brutalized by government troops, forced to become Catholic and other absurdities. Protests were held across South Vietnam, especially Hue. The news media was tipped off to be on hand and signs were written in English as well as Vietnamese to play to U.S. audiences. Finally, in a horrific display a Buddhist monk burned himself alive in the street, on camera, to protest the regime of Ngo Dinh Diem. |

|

|

|

|

President Diem tried to get a handle on the situation, but world opinion continued to turn against him. The Pope criticized his actions, which he feared harmed Christian - Buddhist dialogue, and President Kennedy suspended aid to South Vietnam and began to hint that American support might cease unless South Vietnam came under new leadership. Yet, as in all times past, Diem refused to give in to pressure. Madame Nhu caused a stir when she reiterated the guilt of the Buddhists involved and referred to the incident as a barbecue. She went on a tour of the United States to denounce the liberal policies of the Kennedy administration and was still in the US when word came that a group of generals in Saigon had staged a coup against President Diem. Madame Nhu said her husband and brother-in-law had suspected it for some time and predicted that America would be involved. |

|

|

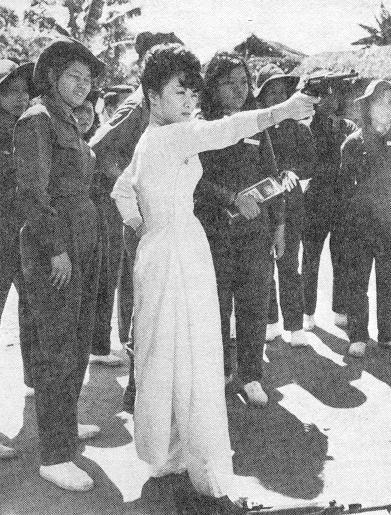

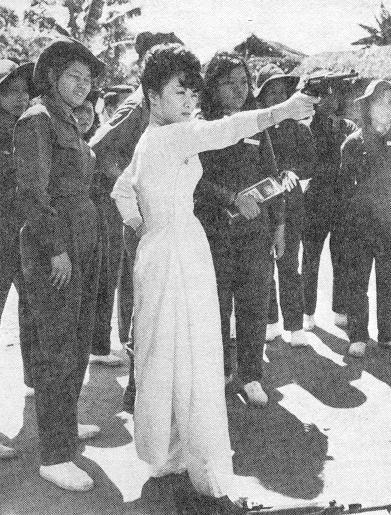

| Madame Nhu and her women warriors |

|

|

| These words turned out to be right on both counts. American officials knew about the coup ahead of time and had given it their blessing. In the end, President Ngo Dinh Diem, Ngo DinhNhu and a priest they were traveling with were all shot by the rebel forces under the overall command of General Duong Van Minh. They were shot after having given themselves up to their enemies and being promised safe passage out of the country. Madame Nhu was understandably furious at the role America had played in the downfall and death of her family. A descendant of the Emperor Dong Khanh and a Catholic convert, she was a proud woman and when President Kennedy was assassinated only three weeks later, when asked if she had anything to say to Mrs. Jackie Kennedy, Madame Nhu replied, 'Now you know what it feels like'. She went into exile in Italy where she lives to this day. Madame Nhu also predicted a dark future for Vietnam and the United States and she was to be proven all too true. |

|

|

| South Vietnam underwent a rapid succession of governments, most of them weak and riddled with corruption as the United States took on the leading role in combating the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese. The war and the unstable climate in Saigon were naturally not beneficial for the Church, but conditions were still preferable to the Communist dictatorship that existed in North Vietnam. The United States steadily increased military support for South Vietnam; however a fear of Red China and the Soviet Union as well as a lack of support from the other major powers meant that US forces would fight only defensively. This meant that no matter how badly the Communists were defeated by American troops, they could simply retreat north to safety to replenish themselves and attack again later. Massive bombing campaigns hurt the Communists, but it was slow work and the main avenues through which the Communists infiltrated the south; through Laos and Cambodia, were strictly off-limits for American personnel. |

|

|

| In 1968 the North Vietnamese launched a massive surprise attack during a cease-fire for the lunar New Year; called Tet. Communist forces, both the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong, attacked every major US installation in what was dubbed the Tet Offensive. For the first time there was combat in the cities of South Vietnam and though the American forces and their South Vietnamese allies defeated the Communist troops; and in fact annihilated the Viet Cong as an effective fighting force, the American media succeeded in turning the Tet Offensive into a propaganda victory for North Vietnam as many in the United States dismissed the war as being impossible to win. The war dragged on for many more years but US forces began a slow withdrawal until pulling out altogether. A cease-fire was negotiated but very few people seriously believed that the Communists would honor it, certainly not the last President of South Vietnam, Nguyen Van Thieu who was also Catholic, and indeed the North had no intention of stopping their aggression. |

|

|

| The Communist leader Ho Chi Minh died in 1969 but it was in his name that the final attack on South Vietnam was launched in April of 1975. The remaining South Vietnamese resistance was crushed and the capitol city of Saigon was captured with the Communist Viet Cong flag being raised over Independence Palace. In honor of her subjugation the Communists renamed Saigon Ho Chi Minh City after their late dictator. Thousands of Vietnamese people were killed or thrown into forced labor camps while hordes more fled their country as refugees to escape the Communist tyranny. Some remained though, such as one defiant Catholic lady whose home was invaded by Communists troops. They found an altar in her house featuring an image of Christ. They ordered her to replace it with a picture of Ho Chi Minh. The Catholic lady staunchly refused, saying that her God had been around a lot longer than theirs had. Somewhat shocked and not wanting to harm a woman of her age, the Communists left, leaving the home of at least one Catholic intact. |

|

|

|

|

| The Church certainly had a great impact on Vietnam, but overtime the Vietnamese also had a significant impact on the Church. A good illustration of this is the case of two sons of the Ngo family, one who had a very positive impact on the Church and another whose contribution was extremely negative. Taking the bad news first we will consider the case of the former Archbishop of Hue Ngo DinhThuc. The eldest brother of President Ngo Dinh Diem, Thuc was made Archbishop of Hue by Blessed Pope John XXIII in 1960, though he may have later regretted the choice as he chastised the Archbishop for his treatment of non-Christians in his diocese. When the end of the personalist republic came Archbishop Thuc was attending the Second Vatican Council and so was one of only two of the Ngo brothers to survive the toppling of the regime (the other was Ngo Dinh Luyen who was ambassador to the Court of St James). Archbishop Thuc never returned to Vietnam and instead relocated to France. |

|

|

|

|

Archbishop Ngo Dinh Thuc |

|

|

| Sadly, from this point on, Archbishop Thuc became more and more involved with radical elements in the Church who opposed new Church policies and rejected the authority of the bishops in union with the Pope at the Second Vatican Council. In 1976 he carried out what was to be the first of many illicit consecrations, done without papal approval, of schismatical and heretical groups. These men then, in turn, illicitly consecrated numerous others and so on and so on so that an entire web of heretical enemies of the Church sprang up thanks to the disobedience of Archbishop Thuc. The first of these declared that Pope Paul VI had been imprisoned and replaced by an imposter and set up their own anti-pope in Spain. A second group indorsed by Thuc went further and claimed that the Holy See had been vacant since the death of Servant of God Pope Pius XII, a position which Archbishop Thuc himself later indorsed in writing. He later consecrated other persons of the so-called Old Catholic Church and of "independent" Catholic churches, none of which are worthy of their universal claims. Pope Paul VI excommunicated Thuc who later repented and asked for the excommunication to be lifted, which was done, though he soon fell back into heresy and brought excommunication upon himself again soon after. He was finally kept in seclusion until his death in 1984 but whether or not he was in full communion with Rome and submission to Pope John Paul II at the end of his life is not known. |

|

|

|

A brighter story is that of a nephew of President Diem, Cardinal Nguyen Van Thuan. As a child his mother had taught him lessons from the Bible and told him stories about his ancestors who were martyred for their Catholic faith. Ordained in 1953 he rose to become deputy Archbishop of Saigon shortly before its fall to the Communists in 1975. Because of his strong Catholic leadership and ties to the regime of President Diem he was singled out for particular cruelty. For thirteen years he was held in a Communist prison camp, spending nine of those years in solitary confinement. He prayed constantly, said mass in his cell with whatever was at hand, made himself a Bible out of scraps of paper and even fashioned a crucifix from bits of wood and wire which he proudly wore for the rest of his life as a reminder of the suffering he had endured. Finally, in 1988, the Communists released him and banished him from the country. He traveled to Rome where Pope John Paul II put him in charge of the Pontifical Council of Justice and Peace, a job for which he seemed ideally suited. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cardinal Nguyen Van Thuan |

|

|

| In 2000 Archbishop Thuan was given the honor of preaching the annual retreat of the Pope and the Roman Curia on his experiences in Vietnam and the call of suffering for the Catholic faith which he lived out. In early 2001 the Pope elevated Archbishop Thuan to the rank of Cardinal Deacon and a short time later the Vietnamese government lifted his banishment. However, by fall of the following year Cardinal Thuan died of cancer in Rome at the age of 74 with the Pope presiding at his funeral. In his life he had witnessed the best and the worst of Catholic life in Vietnam, hearing the stories of the horrible persecutions that came before him, living through a period of freedom for the Church and finally coming full circle to suffer the persecutions of the Communist regime. In his own life he lived much of what the Catholic Church as a whole has been through in Vietnam over the centuries. |

|

|

| Today, the Catholic Church in Vietnam continues to face the enormous difficulties which come from existing in a country with a Marxist inspired government. Although Vietnam has the second largest Catholic population in East Asia, it is still a minority and often persecuted. The Communist government teaches a bizarre collection of often contradictory information to young people to criticize and condemn the Church. For example, state schools in Vietnam vilify the Church for helping the corrupt and oppressive Nguyen Dynasty come to power, yet then also alternately praise these same Nguyen emperors for persecuting the Church and at other times criticize their campaign as an example of the wickedness of monarchy though they themselves have done the same to the Church to a lesser degree. They also like to portray the Church as an instrument of French imperialism and a major collaborator in what they call their enslavement under the colonial system. Yet some state documents also praise Catholics like the mandarin Nguyen Truong To for arguing in favor of reform and modernization. Naturally the propaganda directed at the family of Ngo Dinh Diem and his Catholic supporters and policies are particularly hateful and virulent. There also remains a great deal of difficulty regarding the appointment of bishops and general issues of religious freedom. Although the state of the Church in Vietnam is not as bad as in some other communist countries, it nevertheless faces a great deal of hardships and many lay people and priests are arrested and persecuted for their Catholic faith. |

|

|

| Yet, in spite of all of this, there is reason to hope for better times to come. In recent years, particularly 1988 and 2000, Pope John Paul II canonized a large number of Vietnamese saints who suffered martyrdom for the cause of Christ and the Church. November 24 is the official feast day of the Vietnamese martyrs and their ranks include many shining examples of heroic virtue for all Catholics to follow. We can also take some comfort in the fact that the persecution of the Church is not as bad as it once was and looking at the whole history of Catholicism in Vietnam we can expect better times to come. After all, for as many emperors who persecuted the Church, others came who befriended it and for every hardship Catholics suffered the comforting hand of our Holy Mother was there to give hope and peace in times of heartache. The history of the Church in Vietnam has been bloody and glorious but the Church will go on. What we can do now is pray for the intercession of the Vietnamese saints, Our Lady of Lavang, Our Lady of Tra Kieu and follow their example. We can pray that the country may return to a government more pleasing in the eyes of God and which will allow its people to worship in complete freedom. It may appear to be a hard goal to reach, but there have been times when it looked even harder still and yet the Church did overcome and she can do so again. |

|

|

|

|

|