American History I

Notes from 6/19

We began to discuss the period from 1809 (inauguration of James Madison) through 1828 (election of Andrew Jackson). This is known as a period of nationalism and nation building, in which the United States survived a second war with Great Britain and when Americans began to settle the vast lands of the Louisiana Territory and beyond.

The War of 1812. As noted previously, Jefferson was unable to satisfactorily maintain American neutrality during the protracted conflict between England and France, and his successor, James Madison, became president during a time of heightened tension. The British continued their policy of seizing American ships and "impressing" American sailors into the British navy

Moreover, the British were suspected of instigating Native Americans to violently resist American settlements along the frontier. As white settlers began to push westward, particularly after the Louisiana Purchase (1803), some Native American populations began to mount a more organized resistance. I mentioned the Shawnee spiritual leader Tenskwatawa, also known as the Prophet (page 235), who began preaching about revitalizing native cultures, resisting alcohol, and preventing further encroachments by whites. Although Tenskwatawa preached a form of non-violent resistance, his brother, Tecumseh, advocated the use of force. In 1811, the Governor of the Indiana Territory, William Henry Harrison (a future President), led U.S. troops in a battle against the Shawnee, at a place called Tippecanoe. Although more American lives were lost than Shawnee, this confrontation forced Tecumseh to actively seek British military assistance, a decision which would make the American Congress more hostile towards Great Britain in the months leading up to the War of 1812.

The British also insisted on maintaining a number of forts in the Northwest Territory, despite the provisions of the Treaty of Paris (1783). By 1811, the Congress was increasingly in favor of war with England; "War Hawks" appealed not only to American nationalism but also to the opportunity to expand territorially by taking Canada from the British.

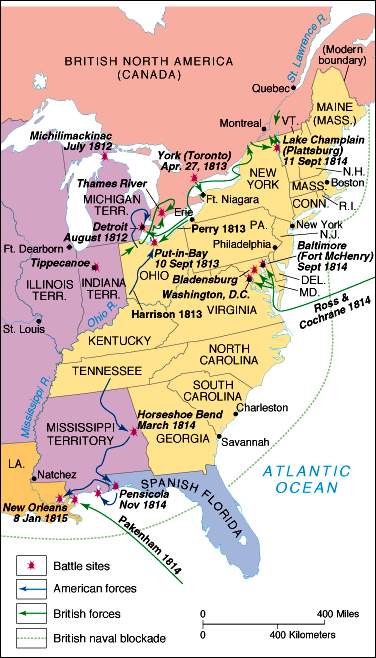

In June 1812, Madison asked for a formal declaration of war. Despite considerable opposition (particularly from New England states), Congress declared war and fighting began along the Great Lakes within a month.

The Treaty of Ghent ended the war in December, 1814, leaving all of the issues that had started the conflict largely unresolved. Because news of the peace took several weeks to reach the United States, fighting continued even after the treaty had been signed. On January 8, 1815, American troops led by Andrew Jackson won an important symbolic victory against the British at the Battle of New Orleans, propelling Jackson to a position of national prominence and a future presidency as well (1829-1837).

Although the war had ended in a draw, the fact that the United States had survived the conflict intact (along with Andrew Jackson's victory in the Battle of New Orleans, which came after the peace treaty), was a source of American pride, and fueled the sense of nationalism that has come to characterize this period. However, the Federalist Party, which had opposed the war, did not survive. As the war drew to a close, Federalists met in Hartford, Connecticut, to discuss ways of amending the constitution to limit presidential powers and strike a better balance of power between northern and southern states. Although the Federalist proposals were fairly conservative, others saw the Hartford Convention, taking place while the country was at war, as something akin to an act of treason. The Federalists were never able to regain their position of political prominence, and ultimately faded into history.

With the War of 1812 over, Americans could focus their attention on expansion and nation-building. The demise of the Federalist Party after the War of 1812 meant that the Democrats would be able to govern without significant opposition for the next few years, until a new political party, known as the Whigs, would emerge.

However, whites perceived the Native American populations that lived east of the Appalachian Mountains as an impediment to progress, and clamored for policies that pushed Indians further west and forced them to cede their lands to the federal government. Beginning in 1815, a series of treaties uprooted various Native American tribes, culminating with the forced removal of the so-called five civilized tribes (Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Creek and Cherokee) from the deep south during the 1830's. Indian removal culminated in 1838 with the forced removal of the Cherokees to the Oklahoma Territory, along what is often referred to as the Trail of Tears. More on that later in the course.

In addition to Indian Removal, westward expansion was also facilitated by a revolution in transportation during this period. Public and private toll roads were built during the 1810's and 1820's; these were moderately successful in increasing access to the frontier regions. The country's extensive system of navigable rivers was probably more important to economic development; the Mississippi, Ohio and Missouri Rivers, and their tributaries allowed for the movement of goods from frontier farms to markets back east. With the development of the steam boat water transportation became much more practical, since goods could be moved both up and down river. Finally, the construction of canals (providing more direct links from eastern cities to the west) became an important element of economic growth during this period. The most notable example from the canal boom was the construction of the Erie Canal in New York. This 364-mile waterway was completed in 1825 and connected New York City with the Great Lakes region, thereby making New York City a much more important center for trade and commerce.

Another thing we talked about during this period was early industrialization. Although the Industrial Revolution would not begin in earnest until after the Civil War, during the 1820's textile factories sprang up, particularly here in southern New England, that became the models for subsequent industrial development. Read the textbook insert (pp. 276-77) on the life of "mill girls" during the 1820's and 1830's.

Westward expansion also highlighted the growing controversy over slavery. As new territories were settled and settlers applied for statehood, the issue arose whether newly admitted states would allow or prohibit slavery. Up through 1817, the north and south maintained a rough balance of power by alternately admitting slave and free states. However, this system was challenged by Missouri's petition for admission as a slave state, which was opposed by northern anti-slavery forces. The Missouri Compromise (1820) admitted Missouri as a slave state, and Maine (which had been part of Massachusetts) as a free state. In addition, subsequent states that were north of Missouri's southern boundary would be free states, and those that were south of Missouri's southern boundary would allow slavery. Of course, implicit in this Compromise was the sense that the United States would continue its course of westward expansion, even if that meant an eventual confrontation with Mexico over territory in the southwest or with Great Britain over the disputed Oregon country.

In terms of foreign policy, the administration of James Monroe (1817-1825) reflected a new era of consensus and an end to the bitter partisanship that had characterized previous decades. Monroe maintained the United States' policy of neutrality; the famous Monroe Doctrine (1823) declared that the U.S. would steadfastly oppose European meddling or expansion in the Americas and that the U.S. would stay out of affairs in Europe. Although the Monroe Doctrine had little immediate effect, the statement became the cornerstone of American foreign policy for the next 100 years.