Return to the Modern European History Page

Directions.

What specific contradictory policies made it impossible for the Allies to fulfill the war-time promises they made?

Point to specific actions taken at the end of the war that contributed to the rise of nationalism among Turks and Arabs.

Note

the significance of all items in bold.

In the new countries

of the Middle East nationalism emerged the most powerful disruptive force at

work in the 1920s. We can begin our survey of this region by looking at a

country where nationalists were determined on the one hand to reject European

imperialists, and on the other to welcome European ideas.

The Ottoman Empire and World War I

The Turkish Empire was in retreat well before the Great War began. In the

First Balkan War of 1912 Turkey was expelled from most of her European

territories, retaining only Thrace, on the tip of the Balkans, and the Turkish

Straits.

Turkey had entered

the war on Germany’s side to halt Russian expansion around the Black Sea.

The British attacked the Ottoman Empire in three separate campaigns.

The first was the disastrous Galllipoli campaign to control

the straits of the Dardanelles. The second was the Mesopotamian Campaign

(perhaps the first in history fought over control of oil supplies); The Turks

resisted fiercely, but by the end of the war, the British were in control of the

key cities of Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq), including Baghdad.

The third campaign

was more glamorous, though its outcome was not at all honorable. The British

planned to support the Arabs in a revolt against their Turkish rulers and

promised that after the war they would help to create independent Arab states in

Iraq, Syria, Palestine and Arabia (today's Saudi Arabia). T. E. Lawrence,

a British Intelligence officer, became a military adviser to the Arabs, and

helped the Arab rulers to build and lead a guerrilla force in attacks on Turkish

railways and supply lines. The daring exploits of this young officer, who became

known as 'Lawrence of Arabia', were a strange, romantic episode in the war. In

the end, the Arab units linked up with the British force that set out from

Egypt, and drove through Palestine and Syria to the frontiers with Turkey.

However, under the Sykes- Picot Agreement (signed in 1916) the

British and the French governments planned to divide much of the Middle East

between them with little thought for the interests of the Arabs. Also

complicating the post-war picture, by the Terms of the Treaty of London of

1915, the Italians had been promised extensive territories in Turkey.

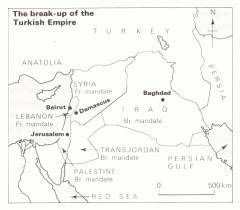

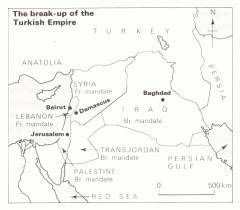

The Break-up of the Turkish Empire

Although in the Great War the Turks scored some major victories over the

British at Gallipoli and in the early states of the Battle of Mesopotamia they

were driven out of their Arab territories in the south by the Arab Revolt of

1917, and by the joint Arab-British offensive in 1918. When Turkey signed an

armistice on 30 October 1918, there was no prospect whatever of the Empire

remaining intact: Emir Feisal, the military commander of the

Arabs, was in control of Syria, Lebanon and Jordan, while the British controlled

1raq and Palestine.

The British and

French felt free to divide the Ottoman Empire between them. Despite Feisal's

pleas at the Paris Peace Conference for Arab independence, the British and

French had already made arrangements for the Arabs in the Sykes-Picot Agreement

of 1916. The British took the lion's share of the land. However, they didn't

want to spend money on troops and officials to rule directly over their new

territories (except in Palestine), and so they set up Arab governments under

their protection in Iraq and Transjordan. The French took a firmer grip on Syria

and the Lebanon, deposing Feisal, who had proclaimed himself King of Syria

earlier in 1920.

Allied plans to take over the Turks' homeland completely misfired. In

1919 Wilson, Lloyd-George, and Clemenceau encouraged the Greek government to

send troops to Turkey to control not only the Turks but also the Italians, who

were already at work in trying to snatch a large chunk of Turkey for themselves.

The Greek government had grand ideas of re-creating the ancient Greek Empire in

a land in which there were large numbers of Greek-speaking people. Turkish

nationalists, led by General Mustafa Kemal, had the simpler

intention of kicking out all Europeans.

Then, in August

1920, the Allies presented the Turkish government with the Treaty of Sevres,

the last of the Paris peace treaties, which dealt harshly with Turkey. Much of

the Turkish heartland was divided into French, Italian and American spheres of

influence, with Smyrna becoming a Greek protectorate. Rather than accept the

dismemberment of Turkey by the Allies, Mustafa Kemal and the nationalists had

already set up a breakaway government in Ankara, in the heart of Turkey.

The war that

followed ended in total victory for Kemal in 1922. Kemal smashed the Greek army

and drove the remnants of it back to Smyrna. There, Turkish civilians promptly

set upon the Greek population of the city in a series of massacres. Pursuing the

Greek army northwards, Kemal then came up against a British garrison guarding

the Turkish Straits. Rather than risk battle with Kemal, the British commander

signed an agreement with him, promising a revision of the Treaty of Sevres in

Turkey's favor. Out of this came a new treaty, the Treaty of Lausanne

in 1923, which left Turkey free of all foreign troops. The Treaty of Lausanne

didn't quite finish the tragedy of the conflict between Greeks and Turks. All

Greeks still living in Turkey and all Turks living in Greece were sent

“home.” Nearly a million and a half people were uprooted from places in

which their families had lived for generations.

Mustapha Kemal, who

later altered his name to Ataturk ('Father of the Turks') declared

a Turkish Republic in October 1923, and ruled it as President until his death in

1938. Ataturk's major achievement was the rapid modernization of Turkey

along Western European lines. He

declared that Islam was no longer the state religion; he introduced the Western

alphabet and forbade writing in Arabic. If male Turks wished to wear headgear

they had to wear Western-style hats or caps, not the traditional 'fez'. In 1934

a law was passed which gave women the vote.

Britain made no really determined effort to stay in Turkey in the face of

nationalist opposition. She and France faced even fiercer resistance from

nationalists in the Arab lands of the Middle East, but there the two European

powers were not prepared to give up their interests.

The Arab lands of the former Turkish Empire were divided between the

British and French and Arabs friendly to the Allied powers. Five new states

emerged from that arrangement--Syria and the Lebanon were French mandates;

Transjordan (Jordan), Iraq and Palestine were British. Only in the Arabian

Peninsula were any of the Arab peoples truly independent. Egypt had been

occupied by British troops since 1914, and for all practical purposes the

British government regarded that country as part of the British Empire. France

imposed direct rule on her Arab territories, Syria and the Lebanon, while the

British arranged that friendly princes ruled Transjordan and Iraq.

Britain's control of Egypt was vehemently opposed by a local nationalist

party, the Wafd, organized led an uprising against the British in Egypt. Although the revolt was not

successful, violence and unrest continued in Egypt until early 1922, when the

British government decided that the only way to put a stop to it (short of

getting out altogether) was to grant Egypt a kind of semi-independence. The

Egyptians were given a form of parliamentary democracy, Sultan Fuad became King

Fuad I, and the number of British officials in the country was steadily reduced.

But the British army remained in occupation, and the Wafd remained a

dissatisfied nationalist party, committed to the overthrow of Europeans who

wouldn't go away.

It was obvious that

neither Britain nor France was prepared to give up control of Arab lands. In

1925 France had to deal with revolts in Syria when nationalists rebelled against

the French policy of supporting Christian Syrians at the expense of the Muslim

Arabs who formed the majority of the population. France granted Syria a new

constitution, but kept control of foreign policy and the armed forces. Similarly

in Iraq, the British granted a kind of independence but insisted on the right to

maintain forces in that country. The security of Suez (and a dawning realization

of the potential oil-wealth) were too important to be left to the chances of

complete independence.

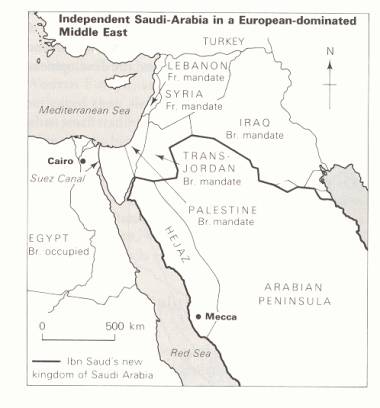

The exception to the

European domination of Arab lands was the Arabian Peninsula. In the early 1920s,

it was rapidly taken over by Ibn Saud, a ruler who had sided with the British

during the war. In 1924 his forces invaded the Hejaz (see map below) and

captured the holy Muslim city of Mecca. In 1926 he was proclaimed King of the

Hejaz, a title he changed to King of Saudi Arabia in 1932.

The Problem of Palestine

To the north of Ibn Saud's

enlarged kingdom, between British Egypt and French Lebanon and Syria,

lay the land, which was to become the focus of Arab nationalism. Back in 1917

the British Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour, had agreed to the

so-called “Balfour Declaration:”

“His Majesty's Government view with favor the establishment in

Palestine of a National Home for the Jewish people, and will use their best

endeavors to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly

understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and

religious rights of existing non- Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights

and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country."

The British had been attracted by the prospect of having a stable,

friendly Jewish community in Palestine as well as by the more romantic idea of

helping the Jews to return to their promised land after nearly two thousand

years in exile. The trouble was that the Arabs were not consulted about the

plan.

At the end of the Great War there were

only 60,000 Jews in Palestine, out of a total population of 750,000; roughly

about seven Jews to every ninety-three Arabs. Yet the Palestine mandate

made Britain responsible for establishing a “Jewish National Home”

there, while at the same time protecting the rights and position of the rest of

the population. It was, of course, an impossible undertaking, and it would

poison relations between the Arabs and the British for many years to come. As

Britain was responsible for Palestine, she was also held responsible by the

Arabs for both the legal and illegal immigration of Jews. By 1931 there were

175,000 Jews in Palestine, or nearly eighteen per cent of the population. It's

possible that the Arabs might have been willing to accept even that sizeable

minority, but sinister developments in Europe in the 1930s would soon bring a

massive influx of Jews to the Middle East. By 1939 there would be nearly 430,000

Jews in Palestine, making up twenty-eight per cent of the population. Arab

nationalists had rightly complained about their treatment at the hands of the

Western powers after the war: the Palestinian problem inflamed their sense of

injustice.

Return to the Modern European History Page