Friday, July 19

Longido, Tanzania

After Mto wa Mbu, we head out to Longido, a Maasai village not too far from the Kenyan border. We make our camp close to the village in a cleared area with no facilities. It's a nice contrast to the busy sites we've been at all week, and later in the evening, it is very dark and very quiet. After getting settled in, we walk over to the village with a local guide, and we're introduced to the patriarch and matriarch in the village. There are a number of woman and children around, but no men or boys -- they are all out tending to the animals, mostly cattle and goats. The Maasai are pastoralists, which means that while they have permanent homes, during the day, they follow their animals. They tend to set up villages for about ten years or so, and then they'll move on to a different location. The Maasai are very traditional, and for the most part, do not send their children to school.

We visit the couple's home, a small mud hut with low ceilings. We all manage to crowd inside the main room, which serves as a kitchen, living room, and bedroom for the man. There are two more small rooms: one where the woman sleeps and the other where some of the animals will sleep when they are young. When a Maasai couple has children, the girls will sleep with the mother and the boys with the father, until they are six or seven; then the children will go to live at the grandparents' home. As we came out of the house, the husband picked up a stick from the roof to show us. Dennis translated for him and told us that the women have a curfew of 6:30 p.m., and if they're not back in the village by curfew, the husband will use this stick to beat them. The man was laughing and smiling as he explained what the stick was used for, and the women standing nearby laughed as well. Needless to say, we were very uncomfortable, and did not know how to respond.

A number of the younger women had just come from some sort of celebration, and in addition to the usual jewelry they wear, had decorated their faces with a rust colored make-up. One of the women had been educated, at the insistence of the Kenyan government when she lived there, and spoke very good English, so we were able to converse with her. My mom pulled out her Polaroid camera and took loads of pictures of the Maasai and gave them to them. She told them to wave the pictures back and forth so they would dry quicker; after about 20 minutes, I realized that many of them were still waving the photos and told Dennis to tell them to stop, otherwise, I was worried that they'd keep waving them all night.

Click here to see more photos of the people of Longido Village.

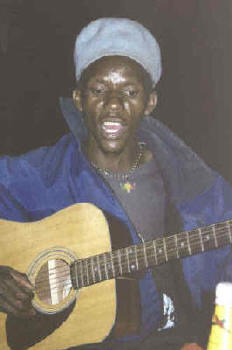

After dinner, our guide, a modernized Maasai, played guitar and sang for us. He had a beautiful voice and sang an odd mix of songs including English songs ranging from Leaving on a Jet Plane, to a number of Harry Belafonte songs Xð; some traditional swahili songs; Jambo Xð, a popular Kenyan song that we heard everywhere; and songs he had written about contemporary problems in the Maasai community including AIDS and the lack of education. That night we could hear hyenas howling Xðjust outside of our camp.

|

|

|

| Making fire from a zebra turd | Everybody wants to be a Masai warrior | Our evening entertainment |

The next day, we hiked up to a cave where the Maasai boys are sent for their warrior training. Boys are circumcised between the ages of 13 and 15, and afterwards, are sent away for about three months to heal and to learn the skills that they need to become warriors. Although the Maasai no longer engage in the type of tribal warfare that they used to, the boys are still trained to kill animals, including lions, and to tend to, and sometimes steal, cattle. We had seen a number of these boys while driving in the area; they are easily recognizable as they have white paint adorning their faces. The place that they stay during their training is a large cave with paintings on the walls. On the way down, we saw where the girls recover after their circumcision: a small, unadorned cave.

We stopped during our walk, and one of the Maasai with us showed us how they use zebra droppings and a stick to start fires; apparently, because zebras eat so much grass, when their droppings dry out, they're highly flammable.

On the way back to Arusha, we stopped at a large Maasai market, which had a wide variety of items for sale, ranging from the traditional Maasai sandals made from old tire treads to the beads used by the women to make their jewelry to modern items like housewares, margarine, and cooking oil. Toward the back of the market was the animal market, where men were buying and selling goats and cattle. We turned around at one point to see a goat being slaughtered.

We arrived back in Arusha mid-afternoon and said good-bye to our guides, drivers, and cooks. All in all, we were very pleased that we had used IntoAfrica for both the Kili trek and the safari. They promote themselves as a fair-minded and fair-traded company, and they really seemed to live up to that standard. All of our guides, cooks, drivers, and porters were knowledgeable and professional as well as just fun to spend time with. In addition, the trips were well-organized, the gear was high quality, and the food was excellent.

Saturday, July 20

Back to the Moivaro Coffee

Plantation Lodge

We had planned to go into town to do some shopping, but never made it. Instead, we hung out at the hotel all afternoon, drinking beer and eating popcorn flavored with freshly grated ginger. We finally managed to get into town to meet Robert, Gareth, and Nico for a last meal at Spices & Herbs, the Ethiopian restaurant. Dinner was delicious, as it had been when we were there before the Kili trek. Gareth, the only non-beer-drinking Brit that we've met, ordered a bottle of red wine from the local Tanganyika Vineyards. While he managed to polish it off, with a little help from Randy, we probably won't be seeing any Tanzanian wines on the international market any time soon.