CHAPTER 66

Lord Ballinmore was laid to rest by

his lonely lady, his peace made, his affairs settled in so far as they could

be, restitution made to William. William would have liked Caroline to remain at

the castle, but she felt drawn to a more challenging life. He assured her that

she would be welcome to return at any time, to visit, or to remain for as long

as she liked. She must always think of it as her home, he said. But the only

home she knew for certain was the old keep of Dunalla with the sea lapping

below its foundation rock. She had taken farewell of William with regret. He

was in good hands. Her beloved Maureen and the faithful Hughy would care for

him, as indeed would all the staff who were only too ready to accept a gentler

regime.

They clung to each other with tears in

their eyes. They said “Goodbye”. But it was not an abrupt parting. William had

connived with Hugh Ro that she should be delayed on her journey. He had lived

too long in a deserted keep not to know its horrors of damp and cold and utter

dreariness. Caroline and Hugh Ro were no sooner well started on their journey

than he organised a surprise for her at the end. A vehicle was packed with

every comfort he could think of or find room for. Maureen and Hughy were then

sent off at speed. They must reach Dunalla well before Caroline. They could

remain there as long as they were needed. Maureen knew the way. This was their

honeymoon.

Caroline and Hugh Ro made one stay on

the journey, spending a few days with the Emsons where they were received with

great kindness. There was so much to talk about, so much tranquillity to gather

from the gentle atmosphere of that gracious home. Hugh Ro felt she needed the

rest, the time perhaps, to change her mind.

So it was Maureen who rushed out with

a welcome to meet the coach, Hughy who helped Owen unyoke the horses, Bridget

who had the kettle on the boil in her warm snuggery. What a feast was laid for

her, what a fire blazed on the hearth in the upper chamber, what a multitude of

candles glimmered in their sconces, how the carved masks winked, how the wall

painting glowed. Even the old wolf at the foot of the stair seemed to grin.

The pale dawn of an October morning

skimmed over the face of the waters. In the creek below Dunalla full tide

lipped the grey rocks. Seaweed ebbed and streamed with the movement of the

water. The air was crisp and still. Only the cry of a seabird stirred the

infinite silence. Hardly a line defined heaven from ocean on the western edge

of the world. Naked as the morning, the girl poised on a jutting rock, her arms

raised to the sky, her blue-green eyes on the almost invisible horizon. There

was nothing between her and the boundless depth and width of sky and sea. One

plunge into the crystal cold, the sting of pain, the drowning and the

resurrection, one gasp for new breath, and life would begin. There was nothing

of the past left except the golden bond that clasped her white thigh. For a few

moments she hesitated, remembering a dream; then, describing a delicate arc,

she dived, and rose, and drew breath, and was refreshed and renewed. In her

element, she swam, at first energetically, then lazily as her body tuned to the

sea's temperature.

Like a mermaid, she rested on the

rock, her bronze-gold hair streaming over pale breast and shoulders, free and

alone with a world that had nothing to offer but hope, which was all she

wanted. Caroline had never been more truly happy, nor yet so sad, as now. Her

sadness was not of regret, for life was a sea over which she had no control

beyond the most trivial choosing. Her sorrow was as inexplicable as the sting

of sea water, as cold and empty as dawn on a western shore.

Hugh Ro, a-stir early after the

journey to Dunalla, met the morning from the crumbling wall above. For an

instant, he saw again that glimpse of beauty that flowering rock of his song,

and bowed his head humbly and made the sign of the cross; for surely it could

not be a man's fate to look on such beauty for the third time and live. Not

that he was not ready to die, as he had been from the first seeing. She had

brought the sealskin rug with her. Now she wrapped it around her. It was as

warm and gentle as the welcome that had greeted her at Dunalla.

It was Hugh Ro who saw the shark, for

he could see far out into the ocean. Was it a shark he saw? No, it did not

behave as a shark would. He stood watching, eyes shaded against the glare of

October light on the water. The object, breaking the surface of the sea, moved

slowly towards land. Eventually he discerned the shape of what appeared to be a

piece of wreckage. He was about to move away when he saw that there was someone

clinging to it. He did not hesitate. Rushing outside and to the edge of the

cliff, he abandoned his boots and outer clothing; then he dived. It was a long

descent and no knowing how it might end for, unfamiliar with this coast, he had

no exact knowledge of where a hidden rock might lie concealed and there was no

time for more than a swift reconnaissance.

Caroline, out of range, saw nothing of

this drama. She had just returned to her rocky perch after a second swim, when

she saw the swimmer toiling slowly into the mouth of the creek. He appeared to

be hampered by something he was lugging. It took a little time to recognise

Hugh Ro and to realise that the object he towed was a human body. Immediately,

she dived to his assistance.

Between them, they dragged the almost

lifeless body to the safety of the rock. While she struggled to a secure perch,

Hugh Ro supported the helpless man. A last heave, and he lay half in and half

out of the water. He lay across her lap, still as a dead man. But he was not

dead. Presently the wound on his head began to bleed again. His blood trickled

down over her belly and thighs, mingling with her own blood from a new wound,

reddening the dry rock, clouding the lipping water. With all her strength she

hauled, till he was clear of the tide and, blended in flesh and blood, their

young bodies lay clasped together on the grey rock at the edge of the world.

Before Hugh Ro wrapped the sealskin rug about them he saw what Caroline had

already seen; the young man from the sea wore a thin gold band about his thigh.

“Fergal,” Caroline crooned, nestling

him in her arms, “Fergal.”

THE END

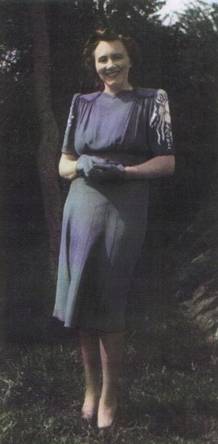

THE AUTHOR

1914 - 1986