FOREVER REMEMBERED

Remember me with smiles and laughter,

for that is how I will remember you all.

If you can only remember me with tears,

then don't remember me at all.

The following are extracts from articles.

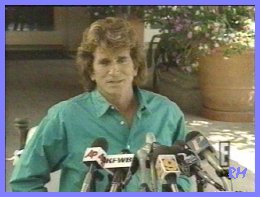

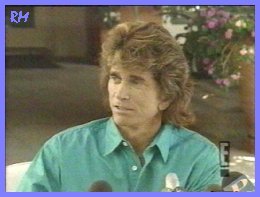

Associated Press (July 2

1991)

Actor Michael Landon, who died yesterday at age 54 after battling cancer, was remembered by his friends and colleagues as a man of warmth, loyalty and unusual courage. “He was a rare individual who was as inspiring and heroic in real life as were the characters that he played on film,” said Jeff Sagansky, head of CBS Entertainment. Ex-President Reagan, a former actor, and his wife, Nancy, said in a statement: “His tragic battle with cancer touched the hearts of every American, as did his undeniable spirit.” Johnny Carson, whose son Richard was killed last week in a car accident, said yesterday: “This has been a devastating week for me and my family. Michael called last Monday expressing his deepest sympathy on the death of my son Ricky. The courage and sensitivity he showed in our conversation, in comforting me while he was in great pain, attests to the quality of this man and his character.” Sagansky said “when I called him, when I first heard that he was ill, the first thing he wanted to know was to make sure that I was OK. He inspired that kind of loyalty. When he believes in you, he believes in you forever. Everything he did came from the heart,” Sagansky said. Actress Melissa Sue Anderson, who played Mary Ingalls on Little House on the Prairie said, “I was 11 when I first met him and those years were difficult for me and he was wonderful. He treated me almost like a daughter,” Anderson said. “He taught me a lot about his philosophy of what work meant. He was always working because he had so much fun doing it.”

Associated Press (July 6 1991)

Eulogies at Michael Landon’s Funeral.

Actor Michael Landon was

eulogized as a man of integrity and humor yesterday as family members and

co-stars of his 'Little House on the Prairie' television series attended a

private funeral service. Former President Ronald Reagan and his wife, Nancy,

were among 500 mourners at a noon ceremony at Hillside Memorial Park and

Mortuary. “I know that Dad wants us to think of him and be filled with love

and happiness and laughter,” said Landon’s da ughter, Leslie Landon Matthews.

She read a poem her father wrote for an episode of 'Little House.' “Remember

me with smiles and laughter, for that is how I will remember you all,” she

read. “If you can only remember me with tears, then don’t remember me at

all.” The 54-year-old actor, familiar to a generation of television viewers as

Little Joe on the long-running 'Bonanza' series, died Monday of liver and

pancreatic cancer at his Malibu ranch. His body was cremated a day later. His

ashes will be interred at Hillside, which also houses the remains of Lorne

Greene, who played Ben Cartwright on 'Bonanza.' The funeral service was heavily

guarded. At the glass and stucco chapel, a dozen guards and sheriff’s deputies

saw to it that only those on a guest list were admitted. But paparazzi lined a

hillside behind the chapel, and the roaring of news helicopters overhead

sometimes drowned out the eulogy. Landon’s 'Little House' co-stars praised him

for his honesty and wit. “Michael’s heart was full of love. He was loved by

everybody,” said Melissa Gilbert-Brinkman, who played his daughter. “After

the death of my own father, in my eyes, he became my father. He was so

special and so basically good. With him, you always knew exactly where you

stood. The man had integrity.” Co-star Merlin Olsen said he was often asked

what Landon was like. “What you saw was what you got’” Olsen said. “He

was a genuine and loving human being, about as fine a boss as you could ever

have. He told me what he wanted me to do, and more importantly, actually

listened to me.” The Reagans, who sat at the front of the chapel, were such

fans of 'Little House' that they sometimes called Landon after an episode they

liked. Jay Eller, his friend and attorney, recalled how Landon was asked what he

would do if, because of chemotherapy, he lost the long, curly hair he cherished.

The attorney said Landon replied: “I’m rich. I’ll buy a hat.” Eller also

read a statement from Landon’s friend, actor Eli Wallach, who mentioned

Landon’s role in 'Bonanza.' “Little Joe has left us,” Wallach wrote.

“Television will miss the richness of his talent.”

ughter, Leslie Landon Matthews.

She read a poem her father wrote for an episode of 'Little House.' “Remember

me with smiles and laughter, for that is how I will remember you all,” she

read. “If you can only remember me with tears, then don’t remember me at

all.” The 54-year-old actor, familiar to a generation of television viewers as

Little Joe on the long-running 'Bonanza' series, died Monday of liver and

pancreatic cancer at his Malibu ranch. His body was cremated a day later. His

ashes will be interred at Hillside, which also houses the remains of Lorne

Greene, who played Ben Cartwright on 'Bonanza.' The funeral service was heavily

guarded. At the glass and stucco chapel, a dozen guards and sheriff’s deputies

saw to it that only those on a guest list were admitted. But paparazzi lined a

hillside behind the chapel, and the roaring of news helicopters overhead

sometimes drowned out the eulogy. Landon’s 'Little House' co-stars praised him

for his honesty and wit. “Michael’s heart was full of love. He was loved by

everybody,” said Melissa Gilbert-Brinkman, who played his daughter. “After

the death of my own father, in my eyes, he became my father. He was so

special and so basically good. With him, you always knew exactly where you

stood. The man had integrity.” Co-star Merlin Olsen said he was often asked

what Landon was like. “What you saw was what you got’” Olsen said. “He

was a genuine and loving human being, about as fine a boss as you could ever

have. He told me what he wanted me to do, and more importantly, actually

listened to me.” The Reagans, who sat at the front of the chapel, were such

fans of 'Little House' that they sometimes called Landon after an episode they

liked. Jay Eller, his friend and attorney, recalled how Landon was asked what he

would do if, because of chemotherapy, he lost the long, curly hair he cherished.

The attorney said Landon replied: “I’m rich. I’ll buy a hat.” Eller also

read a statement from Landon’s friend, actor Eli Wallach, who mentioned

Landon’s role in 'Bonanza.' “Little Joe has left us,” Wallach wrote.

“Television will miss the richness of his talent.”

By Mark Goodman (July 15 1991)

After a ferocious final

battle, Michael Landon succumbed to cancer quickly, quietly - and with the

family he cherished near his bed. To countless television viewers over the last

three decades, Michael Landon was the shaggy -haired, ruggedly boyish

personification of heartland pieties. As Little Joe Cartwright (Bonanza) and

Charles Ingalls (Little House on the Prairie), he radiated the warmth of home,

hearth and old - fashioned American neighborliness, as well as a sense of

bulldog perseverance against all calamities, natural and man - made. As Jonathan

Smith, the angel sublimely aware of earthly troubles in Highway To Heaven, he

traced a path toward a community of the human spirit. Moreover, as a writer,

director and producer, he became a phenomenally successful

entertainment force, one of the few actors to grab the reins of his own career

and harness it to his personal vision. Off screen Landon represented rougher

facets of the American dream. The warmth and sense of familial loyalty were

there to be sure. He fathered six children and adopted three more and clung

fiercely to family rhythms – perhaps, in part, because he was the classic

unhappy child who determined to make, by sheer force of will, the largest

possible imprint upon a hostile world. And so when it was announced on April 8

that Landon, 54, had fallen victim to pancreatic cancer, a stunned public

watched in solemn awe as he turned to make the stand of his life. “If I’m

gonna die,” he told Life magazine three weeks after his diagnosis,

“death’s gonna have to do a lot of fighting to get me.” It was indeed a

hard fight but Landon lost, of course, in a final, painful scene that he wished

only his wife to share. After the discovery of the cancer, which had spread to

his liver, Landon retreated with his third wife, Cindy, 34, and their two young

children to his 10-acre Malibu ranch, where he girded for the battle with a

vegetarian diet, a program of vitamins, enzymes and acupuncture. He  underwent

chemotherapy on April 18. In early May he submitted to an experimental procedure

consisting of intravenous administration of a cancer-fighting drug. These

treatments had little chance of success. Only 3 percent of pancreatic patients

and 5 percent of liver cancer sufferers survive for five years. According to the

American Cancer Society, studies link smoking and alcohol use with these forms

of malignancy. Landon has admitted that he indulged too much in both. Says

retired NBC publicist Bill Kiley: “We used to say we bet his socks smelled

smoky, because he inhaled so deeply.” As word of his condition spread,

thousands of letters of encouragement and sympathy arrived daily. Scores of

friends visited the house and stood vigil at the gates of the ranch. “I have X

amount of energy,” said Landon, “and what I have, I want to spend with my

family.” Landon’s youngest children, Sean, 4, and Jennifer, 7, were

“emotionally distraught,” says longtime

friend and business partner Kent McCray, “but Michael passed his strength

along to them.” Up until the end, says McCray, “his mind was clicking

away….He was telling jokes, he was very lucid, very bright, there was nothing

down about it.” When his publicist, Harry Flynn, wondered two weeks ago

whether to take a short vacation, Landon said, “Don’t be silly. Have a good

time. I’ll be fine.” Says Flynn: “He sounded fine. But then he went

downhill in just a few days.” Over those last days his condition deteriorated

rapidly. On his last weekend, Landon gathered his inner circle at the ranch,

including Cindy, all nine of his children and McCray and his wife. They kept a

vigil in Landon’s upstairs bedroom, where very near the end, according to

McCray, Landon said, “I love you all very much, but would you all go

downstairs and give me some time with Cindy.” She was the only one with him

when he died, at around 1:20 p.m. on Monday, July 1. Landon’s body was

cremated the next day, and at that time, no plans had been announced for a

funeral or memorial service. If his friends and family had solace, it was in

Landon’s extraordinary calm. Says Flynn of his old friend’s last hours:

“It was like going off a diving board. He knew it was coming, and he was brave

to the last.” Landon was a paradoxical perfectionist who spent a lifetime

trying to perform and portray worthy deeds and then kicking tail when anyone got

in his way. “Yes, I am perfect. It’s a problem I’ve had all my life,” he

reportedly snapped to Ed Friendly, co-creator of 'Little House on the Prairie',

during a fierce 1974 argument. (Friendly was gone before the series aired.) This

sense of solitary righteousness – and frontier methods of inflicting his will

– was bred into Landon early. Born Eugene Orowitz on Oct. 31, 1936, in Forest

Hills, N.Y., he grew up with his sister in Collingswood, N.J. His Jewish father,

Eli Orowitz, was a theater manager and film publicist, his Irish-Catholic

mother, Peggy O’Neill, was a minor actress who gave up her career. Eugene

watched his parents bicker endlessly. “Tell your father dinner is ready,”

Landon recalled his mother saying – though Eli was in the room. High school

boys screamed “Jew bastard!” at Landon from passing cars. In a largely

Christian community, fathers wouldn’t allow their daughters to go out with

him. The family and social pressures made him a chronic bed wetter. The

humiliation was increased by his mother’s practice of hanging the soaked

sheets from his bedroom window. College only reinforced his sense of isolation.

Eugene forged himself into a top-flight javelin thrower in high school

and set the national record in his senior year with a record toss of 211 feet 7

inches. That won him a track scholarship to the University of Southern

California. But athlete or no, a dreamy kid from New Jersey with curly,

shoulder-length hair was not likely to be welcomed on a crew-cut 1950s campus.

His teammates mocked him and even pinned him down and cut off his hair. Landon,

furious, threw his arm out on a toss, lost his scholarship and soon quit school.

Even before the haircut and the lost scholarship came a melancholy moment that

made an even deeper wound in Landon. In 1954 Landon journeyed to L.A. with his

publicity-agent father, who believed that his former colleagues at RKO Radio

Pictures, by now Paramount studios, would offer him a job. “Wait here,” he

told his son at the gate. I’ll be back in a minute.” Thirty minutes later

his father returned, crestfallen; he couldn’t even get past the guard. Years

later Landon told a reporter that the humiliating moment spawned a life’s

decision. “No matter what I did,” he said, “I wasn’t going to owe

anybody a favor. And I didn’t expect anything from anybody that had to do with

business….I wasn’t going to take any garbage from anybody, either.” As it

turned out, he didn’t have to: A film executive spotted him and suggested that

he enroll in Warner Bros. Acting school. Soon, Landon was performing in

prestigious TV productions on Studio One and G.E. Theater. He made his movie

debut in 1957 in a cult favorite of the day, I Was A Teenage Werewolf – as its

werewolf star. At about the same time, Landon began a stormy marital career. In

1956 he married legal secretary Dodie Fraser, a relationship that lasted six

years. He adopted Dodie’s son, Mark, and another boy, Josh. The couple

divorced in 1962, and in 1963 Landon married model Lynn Noe, with whom he had

four children (Michael Jr., Christopher, Leslie and Shawna). He also adopted

Noe’s daughter Cheryl. His acting career really took off when he landed the

role of Little Joe in bonanza, the first Western series broadcast in color.

Landon, Lorne Greene, Dan Blocker and Pernell Roberts made the widowed

Cartwright and his boys the first family of the West, and the show enjoyed a

14-year run. Greene took Landon under his wing and once described him this way:

“Mike’s a very sweet guy but extremely stubborn….He’s too impulsive.

Mike will do a thing one day that he’ll regret eight days later. When it comes

to a sense of humor, Mike has a terrific one.” Roberts didn’t think so. He

and Landon – who by the mid-60s was also directing episodes – clashed on the

set. Roberts left the show after six years. (Now Bonanza’s last survivor,

Roberts would say nothing more last week but that he was “deeply grieved by

Michael’s death.”) Landon’s single-minded ferocity began to unfold during

the Bonanza years. To cope with his emerging fame, during the show’s second

season, he began popping dozens of tranquilizer pills a day. He eventually

kicked the pill habit. “I still work long days,” Landon once conceded of his

tendency toward overdrive. “I’ve always had to work very hard in order to be

happy.” In his last weeks at the ranch, his illness drew the attention of

hundreds of thousands of fans, many of them young TV viewers who had grown up

with Landon as our culture’s most visible repository of a sense of common

decency, of the moral fitness of things. This universal chord struck by Landon

was echoed by his old colleague, former President Ronald Reagan, who said,

“His tragic battle with cancer touched the hearts of every American, as did

his indomitable spirit.” And Landon closed his own book with a stolid grace

that refused to succumb to tragedy. “It’s not like I’ve missed a hell of a

lot,” he said. “I’ve had a pretty good lick here.”

underwent

chemotherapy on April 18. In early May he submitted to an experimental procedure

consisting of intravenous administration of a cancer-fighting drug. These

treatments had little chance of success. Only 3 percent of pancreatic patients

and 5 percent of liver cancer sufferers survive for five years. According to the

American Cancer Society, studies link smoking and alcohol use with these forms

of malignancy. Landon has admitted that he indulged too much in both. Says

retired NBC publicist Bill Kiley: “We used to say we bet his socks smelled

smoky, because he inhaled so deeply.” As word of his condition spread,

thousands of letters of encouragement and sympathy arrived daily. Scores of

friends visited the house and stood vigil at the gates of the ranch. “I have X

amount of energy,” said Landon, “and what I have, I want to spend with my

family.” Landon’s youngest children, Sean, 4, and Jennifer, 7, were

“emotionally distraught,” says longtime

friend and business partner Kent McCray, “but Michael passed his strength

along to them.” Up until the end, says McCray, “his mind was clicking

away….He was telling jokes, he was very lucid, very bright, there was nothing

down about it.” When his publicist, Harry Flynn, wondered two weeks ago

whether to take a short vacation, Landon said, “Don’t be silly. Have a good

time. I’ll be fine.” Says Flynn: “He sounded fine. But then he went

downhill in just a few days.” Over those last days his condition deteriorated

rapidly. On his last weekend, Landon gathered his inner circle at the ranch,

including Cindy, all nine of his children and McCray and his wife. They kept a

vigil in Landon’s upstairs bedroom, where very near the end, according to

McCray, Landon said, “I love you all very much, but would you all go

downstairs and give me some time with Cindy.” She was the only one with him

when he died, at around 1:20 p.m. on Monday, July 1. Landon’s body was

cremated the next day, and at that time, no plans had been announced for a

funeral or memorial service. If his friends and family had solace, it was in

Landon’s extraordinary calm. Says Flynn of his old friend’s last hours:

“It was like going off a diving board. He knew it was coming, and he was brave

to the last.” Landon was a paradoxical perfectionist who spent a lifetime

trying to perform and portray worthy deeds and then kicking tail when anyone got

in his way. “Yes, I am perfect. It’s a problem I’ve had all my life,” he

reportedly snapped to Ed Friendly, co-creator of 'Little House on the Prairie',

during a fierce 1974 argument. (Friendly was gone before the series aired.) This

sense of solitary righteousness – and frontier methods of inflicting his will

– was bred into Landon early. Born Eugene Orowitz on Oct. 31, 1936, in Forest

Hills, N.Y., he grew up with his sister in Collingswood, N.J. His Jewish father,

Eli Orowitz, was a theater manager and film publicist, his Irish-Catholic

mother, Peggy O’Neill, was a minor actress who gave up her career. Eugene

watched his parents bicker endlessly. “Tell your father dinner is ready,”

Landon recalled his mother saying – though Eli was in the room. High school

boys screamed “Jew bastard!” at Landon from passing cars. In a largely

Christian community, fathers wouldn’t allow their daughters to go out with

him. The family and social pressures made him a chronic bed wetter. The

humiliation was increased by his mother’s practice of hanging the soaked

sheets from his bedroom window. College only reinforced his sense of isolation.

Eugene forged himself into a top-flight javelin thrower in high school

and set the national record in his senior year with a record toss of 211 feet 7

inches. That won him a track scholarship to the University of Southern

California. But athlete or no, a dreamy kid from New Jersey with curly,

shoulder-length hair was not likely to be welcomed on a crew-cut 1950s campus.

His teammates mocked him and even pinned him down and cut off his hair. Landon,

furious, threw his arm out on a toss, lost his scholarship and soon quit school.

Even before the haircut and the lost scholarship came a melancholy moment that

made an even deeper wound in Landon. In 1954 Landon journeyed to L.A. with his

publicity-agent father, who believed that his former colleagues at RKO Radio

Pictures, by now Paramount studios, would offer him a job. “Wait here,” he

told his son at the gate. I’ll be back in a minute.” Thirty minutes later

his father returned, crestfallen; he couldn’t even get past the guard. Years

later Landon told a reporter that the humiliating moment spawned a life’s

decision. “No matter what I did,” he said, “I wasn’t going to owe

anybody a favor. And I didn’t expect anything from anybody that had to do with

business….I wasn’t going to take any garbage from anybody, either.” As it

turned out, he didn’t have to: A film executive spotted him and suggested that

he enroll in Warner Bros. Acting school. Soon, Landon was performing in

prestigious TV productions on Studio One and G.E. Theater. He made his movie

debut in 1957 in a cult favorite of the day, I Was A Teenage Werewolf – as its

werewolf star. At about the same time, Landon began a stormy marital career. In

1956 he married legal secretary Dodie Fraser, a relationship that lasted six

years. He adopted Dodie’s son, Mark, and another boy, Josh. The couple

divorced in 1962, and in 1963 Landon married model Lynn Noe, with whom he had

four children (Michael Jr., Christopher, Leslie and Shawna). He also adopted

Noe’s daughter Cheryl. His acting career really took off when he landed the

role of Little Joe in bonanza, the first Western series broadcast in color.

Landon, Lorne Greene, Dan Blocker and Pernell Roberts made the widowed

Cartwright and his boys the first family of the West, and the show enjoyed a

14-year run. Greene took Landon under his wing and once described him this way:

“Mike’s a very sweet guy but extremely stubborn….He’s too impulsive.

Mike will do a thing one day that he’ll regret eight days later. When it comes

to a sense of humor, Mike has a terrific one.” Roberts didn’t think so. He

and Landon – who by the mid-60s was also directing episodes – clashed on the

set. Roberts left the show after six years. (Now Bonanza’s last survivor,

Roberts would say nothing more last week but that he was “deeply grieved by

Michael’s death.”) Landon’s single-minded ferocity began to unfold during

the Bonanza years. To cope with his emerging fame, during the show’s second

season, he began popping dozens of tranquilizer pills a day. He eventually

kicked the pill habit. “I still work long days,” Landon once conceded of his

tendency toward overdrive. “I’ve always had to work very hard in order to be

happy.” In his last weeks at the ranch, his illness drew the attention of

hundreds of thousands of fans, many of them young TV viewers who had grown up

with Landon as our culture’s most visible repository of a sense of common

decency, of the moral fitness of things. This universal chord struck by Landon

was echoed by his old colleague, former President Ronald Reagan, who said,

“His tragic battle with cancer touched the hearts of every American, as did

his indomitable spirit.” And Landon closed his own book with a stolid grace

that refused to succumb to tragedy. “It’s not like I’ve missed a hell of a

lot,” he said. “I’ve had a pretty good lick here.”

By Ellen Grehan (July 16 1991)

Within an hour after Michael passed away, Cindy walked through the gardens of her estate with two of Michael’s daughters from his previous marriage. Cindy said her final goodbye to her husband as the mortuary attendants drove his remains away from the Malibu, Calif., ranch he loved so much.

By Timothy Carlson (July 20 1991)

Shortly after 1pm on the afternoon of Monday, July1, Michael Landon's three-month battle against inoperable cancer of the pancreas and liver came to an end. The 54 year old star of three of television's most beloved and enduring family series - Bonanza, Little House on the Prairie and Highway To Heaven - had sensed that the end was near on the Friday before he died, reports his longtime publicist, Harry Flynn. "He had a lot of pain and he was very uncomfortable. He was coughing at night and it was not pleasant." Landon's condition worsened, his wife, Cindy, who had been his mainstay throughout the ordeal, gathered his nine children, ranging in age from 42 to 4, and a few close friends at the couple's Malibu home. They talked, they touched and they hugged one another throughout the weekend. "He was in pain, there was no question," says Kent McCray, Landon's longtime partner, who visited him with his wife Susan, the day he died. "His legs, from the phlebitis, were giving him pain. The cancer itself was giving him pain. It was tough to digest anything. But his mind at all times was extremely alert. He looked up at Susan and said, 'I like your jacket, and I love your glasses.' He always remarked on how people looked. This is where his mind was. He had his faculties right until the end. His spirits were up. The love was vary evident in everybody." Landon spent a peaceful Monday morning. But, then, weakened by his struggle against the disease and attached to a morphine drip that barely masked the pain he was feeling, Landon told his children: "I love you all, but go downstairs now. I want to be alone with Cindy." After a few moments in private with his third wife whom he adored, Michael Landon passed away. "When he was gone, everybody went back up and, in their own way, said their goodbyes to him," says McCray.

Landon

had chosen to face death alone with his wife because he knew "it would not

be easy for the children," says Flynn. "He was a very caring guy. His

thoughts were for everyone else." Karen Grassle, who played his wife on

Little House, perhaps best summarizes the legacy Landon leaves - and the sense

of loss his friends now feel - when she says: "I prayed for a miracle for

Michael, and I am devastated by the news of his death. I knew what his prognosis

was. But, the thing is, he believed in miracles. In some ways, that was his

message, his legacy." Upon hearing the news of his death, Melissa

Gilbert-Brinkman, who played his daughter on Little House, said: "There is

a big hole in my heart....He was like a father to me. He was my friend. I will

miss him so much. But I will carry his legacy on in my life, in my work and in

my heart forever."

miracles. In some ways, that was his

message, his legacy." Upon hearing the news of his death, Melissa

Gilbert-Brinkman, who played his daughter on Little House, said: "There is

a big hole in my heart....He was like a father to me. He was my friend. I will

miss him so much. But I will carry his legacy on in my life, in my work and in

my heart forever."

The day after Landon died, the cast and crew who had been with him for nearly 30 years and who were like a family gathered at the Malibu compound to share their grief. There was much talk of Landon's love of practical jokes, says Flynn, how he'd have frogs pop out of his mouth at the most inappropriate times. He kept his sense of humor till the end, Flynn recalls. "I called him a few weeks ago and I said: 'God, you sound great!' He said: 'It isn't my voice that's sick, Harry!' But the overwhelming feeling amoung the mourners was an eerie sense of displacement, as if the earth had shifted for them. "When we all got together in the room, it was like, 'Here we are without our Daddy,' says Flynn. That sounds terrible, but it was the truth. We were just realising we had to go on without him."

"People ask me what will happen to Michael Landon Productions," says McCray. "It can't go on without the leader. I would like to try, in my way. I feel there is a need for the kind of stories he produced. People do want them. How am I going to handle it, I don't know. But Michael always said, 'You've got to go on. One person out of the link doesn't mean you come to a stop.' Thank goodness for syndication, for it means the legacy will go on and on."

By Cindy Landon as told to Brad Darrach (December 1991)

I still can’t believe

Michael is gone. I wake up in the middle of the night and stare at the ceiling,

feeling so lonely and lost. I can’t wait for morning to come, because then

I’m up and doing for the kids and I can push the ache away. Thank God I’ve

got the little ones. Sometimes they drive me crazy – Jennifer is eight and

Sean is five and believe me, they’re a handful –but I don’t know what

I’d do without them. They miss Michael terribly too. When I asked Sean why he

never speaks about his father, his lip began to tremble and he said in a quavery

voice, “Because it makes me sad.” And the other day Jennifer taped a note to

her bedroom door. “Please come in Mom or Dad if he’s back.” The whole year

has been a strange and terrible dream. Michael was so incredibly strong and

vital, and he was only 54. All he needed was four hours’ sleep a night, and

just weeks before the symptoms started he was bench-pressing 350 pounds. Then in

early February he began having abdominal pains. But you could never get Michael

to a doctor. Finally I made the appointment, and they examined him for an ulcer.

Nothing there, but they gave him some medicine and it seemed to help. Then, in

March, just before we took a holiday to Utah, the pains came back strong and I

told him if he didn’t go in for a lower-GI we weren’t going on vacation.

Well, I knew he didn’t have the test, but he came home with some more stomach

medicine and we went. On the trip he was in tremendous pain, and I got scared. I

thought maybe he had an intestinal blockage, so I got him to fly home a day

early and take tests. That night he called me and said it was a problem with his

pancreas. He tried to sound calm, but there was something in his voice. I found

out later that the doctors had already told him it was a large tumor on the

pancreas, probably a cancer that had spread to the liver, and that he had a few

months or at most a year to live. Anyway, I freaked out and started to cry. He

tried to comfort me, but when I said I was flying home immediately he didn’t

hang tough in his usual way. He just said, “Yeah.” Then I really knew, and I

felt horrible because he needed me and I wasn’t there. Two days later we had

the results of the biopsy:

pancreatic cancer that had metastasized to the liver.

It was a death sentence. Less than a 1 percent chance of a cure. My whole body

went numb. It was like I was in a movie and watching it at the same time, like I

was going through the motions but it wasn’t really me. Then suddenly I felt

this surge of anger. Anger at life, at everything. Why is this happening? It

isn’t fair! But the next day I saw an old woman begging on a street corner. My

heart just went out to her, and I gave her some money. And suddenly the anger

was gone. At first Michael was stunned, too, but he never got angry, never gave

in to self-pity, never cursed his fate. He just faced the truth and made himself

live with it. He faced death, and he wasn’t afraid, not for a minute. He

believed in God, and I think he was actually curious about what came next – he

looked at dying as another journey. He didn’t want to die, don’t get me

wrong. He loved his work, loved his family, loved his life. He hated leaving

everything he loved. I can still see him sitting in a wheelchair in the hallway

of the hospital, looking at me with tears in his eyes and saying quietly,

“Cindy, this is just the beginning.” He meant the beginning of a very bad

time, but he also meant the beginning of our fight to save his life. It was a

fight we lost, but we fought hard, and we fought every step of the way together.

I prayed every day for a miracle, for Michael to beat this thing. Michael

prayed, too, but not like: Please God, don’t let me die. He just prayed for

us, and for the strength to accept whatever happened. “It’s not God that

does it,” Michael often said. “It’s the disease that does it. God

doesn’t give you cancer.” We prayed and worked and planned what we had to

do. I told Michael we had to tell the whole family right away, because it would

be terrible if Jennifer and Sean heard it first at school of if the older

children heard it on a newscast. So we made telephone calls to the family, and

then we sat down with Jennifer and Sean. We told them that Daddy had a very

serious type of cancer, that Daddy could die, that Daddy was going to try not

to. We told them calmly, and Sean seemed to take the news fairly calmly, but

I’m not sure he really understood. Jennifer had some rough moments.

Michael’s older children were devastated by the news. But we agreed we

weren’t going to give up. We went looking for cures. The doctors wanted him to

start chemotherapy right away, but they admitted that there had rarely been a

case of pancreatic cancer cured by chemo. Besides, Michael hated the idea of

filling his body with poison, and so did I. But it turned out that pancreatic

cancer had more often been cured by alternative methods. So we tried a holistic

approach. He went on a diet of creamed papaya supplemented by fruit and

vegetable juices, 13 pints a day. He also ate oatmeal and brown rice, and took

large doses of vitamins and enzymes to build up his immunity. Right away the

pain in his abdomen went away and he began to feel much better, almost like his

old self. He kept improving, until after about three weeks he began to believe

that, against all the odds, he was getting better. So he decided to have a

second CAT scan to prove that the doctors were wrong. I remember sitting there

in a radiologist’s office, waiting for the pictures to be developed. We were

hopeful, but terribly anxious too. Then we saw the pictures, and I felt as if

I’d been kicked in the stomach. Michael took one look and said, “It’s

grown.” In less than three weeks the cancer had almost doubled in size. On the

way home in the limo we didn’t say much. Up to that point I don’t think

Michael had really  and truly believed that he was going to die, and I know I

hadn’t. That afternoon, for the first time, we both realized what lay ahead.

He was in shock, and I was terribly scared. I just lay with my head on his lap

and cried. He stroked my hair and said, “I know, I know.” When we got home,

the kids were back from school, happy and excited, and I looked at them and for

the first time I thought: Maybe my babies are going to lose their father. As

soon as we could, we sent them out to play. Then we went upstairs and lay down,

and held each other, and cried. That’s the way we were. Incredibly close.

After 13 years, incredibly much in love. We were simply meant to be together.

Then, now, forever. After all those years, when Michael would come home early,

my heart could start beating hard just to see him come in that door. Oh, I’m

not saying we didn’t have disagreements. Who doesn’t? We’d disagree at

times, for instance, about the kids’ bedtimes and table manners – he was

easygoing, I was more the disciplinarian. Michael often told me I was full of

fire, and he liked that about me. I enjoy life and I like to laugh. And I’m

very loving. So was Michael. We nourished our love and it kept growing. We were

soul mates. I’m a down-to-earth person, so I know it sounds silly, but every

little girl dreams of meeting her prince. I met mine. I had a fairy-tale

marriage. It was that way from the start. I was 19 when I was hired as a

stand-in on Little House on the Prairie. I was romantic, and the minute I laid

eyes on Michael I got this terrible crush. I thought he was the most handsome,

brilliant, witty, exciting man I’d ever seen – it’s true, I still think

so. But I didn’t seriously imagine we’d ever be together. Michael was

married, and I wasn’t setting out to capture a married man. What I didn’t

know was that Michael and his wife, Lynn, had grown apart. Anyway, as time went

on, I noticed him watching me, and I thought: Am I imagining things? But he

really was watching me, and this made me very excited. He began to do little

things. Like he would bring me a snow cone. So I would bring him a yogurt. Then

one day he thought he heard me say I like a man with hair on his chest, so he

went to the makeup room and came out with this huge wad of false hair sticking

out of his shirt. I cracked up. But gradually things got more serious. One night

I went to my car and there was a tiny stuffed animal on the seat, and a tender

note. Another time there were roses. My heart just got – crazy. I thought

about him all the time. Finally, after I’d been with the show almost a year,

he came to my apartment one night after a party on the set. After that we were

like love struck teenagers. I remember our first date. We went to see Monty

Python and the Holy Grail and ate popcorn and held hands in the dark. Sometimes

he’d drive by my apartment in his green Ferrari and shout out the window, “I

love you, Cindy Clerico!” I mean, in broad daylight! In Beverly Hills! I

thought: This man is nuts. The fact is he was ready to make the break with his

wife. He wanted to get caught. He wanted to be happy. Michael had everything,

everything to live for. His family and his work were thriving. He’d just

finished the pilot for his new series, Us, and he told me it was going to be the

best he had ever done, the story of a real person with real problems and real

faults. He’d also signed a deal to make theatrical movies, and he was writing

the script for his first picture when he found out he had cancer. He was so

resilient, but the second cat scan knocked a lot of the fight out of him. He

didn’t altogether give up – the next morning it was, "OK, what do we try

now?" – but I think he stopped really believing he could get well. I know he

stopped believing he could get well just by keeping to his diet and building up

his immune system. So we went back to the oncologists, and they told him his

only hope was chemotherapy. They proposed some new, experimental forms of chemo

that sounded promising, and he gave the go-ahead. He hated the idea, but he felt

he had to try something because he loved us and didn’t want to leave us. Right

after heavy chemotherapy began, things started to go downhill. He had regular

episodes of internal bleeding, and dangerous clots would form without warning.

One evening, after the kids were in bed, we kicked back in the family room and

started to watch a movie, and we both thought: Gee, isn’t this great?

Everything seems so normal, just like old times. Then all at once Michael felt a

terrible pain in his leg. It was a blood clot, and we had to rush off to the

hospital, 40 miles away. Finally he had a tiny “umbrella” as the doctors

called it, put in a vein, and that stopped the clots from going to his heart or

his lungs. But the surgical procedure left him with a secondary infection, and

he had to go on antibiotics. And so it went, on and on. Michael fought back. The

day

and truly believed that he was going to die, and I know I

hadn’t. That afternoon, for the first time, we both realized what lay ahead.

He was in shock, and I was terribly scared. I just lay with my head on his lap

and cried. He stroked my hair and said, “I know, I know.” When we got home,

the kids were back from school, happy and excited, and I looked at them and for

the first time I thought: Maybe my babies are going to lose their father. As

soon as we could, we sent them out to play. Then we went upstairs and lay down,

and held each other, and cried. That’s the way we were. Incredibly close.

After 13 years, incredibly much in love. We were simply meant to be together.

Then, now, forever. After all those years, when Michael would come home early,

my heart could start beating hard just to see him come in that door. Oh, I’m

not saying we didn’t have disagreements. Who doesn’t? We’d disagree at

times, for instance, about the kids’ bedtimes and table manners – he was

easygoing, I was more the disciplinarian. Michael often told me I was full of

fire, and he liked that about me. I enjoy life and I like to laugh. And I’m

very loving. So was Michael. We nourished our love and it kept growing. We were

soul mates. I’m a down-to-earth person, so I know it sounds silly, but every

little girl dreams of meeting her prince. I met mine. I had a fairy-tale

marriage. It was that way from the start. I was 19 when I was hired as a

stand-in on Little House on the Prairie. I was romantic, and the minute I laid

eyes on Michael I got this terrible crush. I thought he was the most handsome,

brilliant, witty, exciting man I’d ever seen – it’s true, I still think

so. But I didn’t seriously imagine we’d ever be together. Michael was

married, and I wasn’t setting out to capture a married man. What I didn’t

know was that Michael and his wife, Lynn, had grown apart. Anyway, as time went

on, I noticed him watching me, and I thought: Am I imagining things? But he

really was watching me, and this made me very excited. He began to do little

things. Like he would bring me a snow cone. So I would bring him a yogurt. Then

one day he thought he heard me say I like a man with hair on his chest, so he

went to the makeup room and came out with this huge wad of false hair sticking

out of his shirt. I cracked up. But gradually things got more serious. One night

I went to my car and there was a tiny stuffed animal on the seat, and a tender

note. Another time there were roses. My heart just got – crazy. I thought

about him all the time. Finally, after I’d been with the show almost a year,

he came to my apartment one night after a party on the set. After that we were

like love struck teenagers. I remember our first date. We went to see Monty

Python and the Holy Grail and ate popcorn and held hands in the dark. Sometimes

he’d drive by my apartment in his green Ferrari and shout out the window, “I

love you, Cindy Clerico!” I mean, in broad daylight! In Beverly Hills! I

thought: This man is nuts. The fact is he was ready to make the break with his

wife. He wanted to get caught. He wanted to be happy. Michael had everything,

everything to live for. His family and his work were thriving. He’d just

finished the pilot for his new series, Us, and he told me it was going to be the

best he had ever done, the story of a real person with real problems and real

faults. He’d also signed a deal to make theatrical movies, and he was writing

the script for his first picture when he found out he had cancer. He was so

resilient, but the second cat scan knocked a lot of the fight out of him. He

didn’t altogether give up – the next morning it was, "OK, what do we try

now?" – but I think he stopped really believing he could get well. I know he

stopped believing he could get well just by keeping to his diet and building up

his immune system. So we went back to the oncologists, and they told him his

only hope was chemotherapy. They proposed some new, experimental forms of chemo

that sounded promising, and he gave the go-ahead. He hated the idea, but he felt

he had to try something because he loved us and didn’t want to leave us. Right

after heavy chemotherapy began, things started to go downhill. He had regular

episodes of internal bleeding, and dangerous clots would form without warning.

One evening, after the kids were in bed, we kicked back in the family room and

started to watch a movie, and we both thought: Gee, isn’t this great?

Everything seems so normal, just like old times. Then all at once Michael felt a

terrible pain in his leg. It was a blood clot, and we had to rush off to the

hospital, 40 miles away. Finally he had a tiny “umbrella” as the doctors

called it, put in a vein, and that stopped the clots from going to his heart or

his lungs. But the surgical procedure left him with a secondary infection, and

he had to go on antibiotics. And so it went, on and on. Michael fought back. The

day after he had a liver biopsy he showed up at the gym and did a brisk workout

on the Gravitron machine. Yet as the cancer progressed, the pain in his liver

became intense. We had two nurses in the daytime, but in the evenings Michael

and I were alone together. We had long talks. “Think how lucky we’ve

been,” He’d say. “How lucky we met. How lucky we’ve had all these

wonderful years together.” And he’d say, “Cindy, if I’m going to die,

it’s probably better if I die now than if I died in ten years. You’re still

young, and it’ll be easier for you to get on with your life.” I wanted to

scream when he said things like that, but I just smiled and passed on to the

next thing. I knew he was trying to soften the blow. As the weeks went by the

pains got worse, and we had to put him on morphine and percocet. He got a little

thinner, too, but he was never down to 90 pounds, like the tabloids said, and

thank God the chemo didn’t make his hair drop out. Even there, Michael turned

his anxiety into a joke. He said if he lost his hair they could put his picture

on the cover of Bowlers’ Journal. The sense of humor was there to the end, but

as he got weaker his sadness grew. I’d walk into the bedroom and find him

crying quietly. When I’d ask what was wrong, he’d say, “It’s not seeing

you again.” When the children came in, he’d look at them so long and so

intensely – as though trying to take in everything about them. He would touch

their hands and faces, and tears would fill his eyes. But he had no regrets, no

feeling he should have lived life differently. He’d done what he wanted to do

and done it with all his strength, and that was that. Finally the day came when

he said, “Cindy, I’m dying. I can feel it in my body. I’ve got a week to

live.” He was right. He died exactly one week later. All that last week I saw

him fading. Somehow the reporters knew and came swarming around like vultures.

It was a deathwatch. I was outraged and so was Michael. “What is this,” he

said, “some sort of frigging game?” On Sunday morning, June 30th,

I knew the end was near, so I called all his children and his closest friends,

and they came to the house. Michael was Michael. Very alert. Talking with

everybody and joking. Later in the day he began dozing, off and on. The pain got

worse, and we had to increase his morphine and percocet. The nurses said the end

could come at any time, so we stayed there with him through the afternoon and

into the night. Michael drifted into a dreamlike state, neither awake nor

asleep, and began talking in a rambling way. Then he started coughing up blood.

At about 11 o’clock, everybody went off to get some sleep. I stayed with him

through the night. In the morning everybody gathered around his bed again –

Jennifer and Sean were there too – and we were all crying because we knew it

was the end. Then all of a sudden Michael became completely alert, sat up,

looked around at all of us standing there and said, “Oh, hi guys.” And he

smiled and said, “I love you very much.” Everybody was startled and very

emotional. But pretty soon they said goodbye because Michael didn’t want a lot

of people watching him when he died. When I was there with him alone, we talked

a little and hugged. The he went back into the dreamlike state and began

rambling and waving his arms. I realized that he was directing a movie in his

mind. “Put a 50 over here,” he said – a 50 is a stage lamp. “Tell that

guy he’s lying the wrong way.” Then he started writing in the air, and a

minute later he sat up and actually pulled on a pair of imaginary boots. After

that he grabbed my blouse and tried to tie it in a bow. I told him to relax,

calm down, because his movements were getting frantic. I asked him, “Do you

know who I am?” He said, looking right at me, “Mm. Yeah.” And I said, “I

love you.” And he said, “I love you too.” Those were Michael’s last

words. He lay down and began breathing heavily. Pretty soon his breathing became

deeper and less frequent. I called the nurse, who came running in and put a

stethoscope to his chest. Michael took one last breath, and was gone. I just sat

there beside him. I was numb. I couldn’t believe what had just happened. I

don’t remember if I said anything. I just remember that I sat there. Ten

minutes, 15 minutes. Then I went downstairs and told everybody that Michael was

gone, and they came up to the bedroom again. All at once there was a terrible

roaring overhead. It was a helicopter from one of the television stations! I

couldn’t believe it. How dare they take this moment from us! Then the roaring

went away, and we all sat there with Michael a little while longer. Suddenly we

heard screaming. It was Jennifer, who

after he had a liver biopsy he showed up at the gym and did a brisk workout

on the Gravitron machine. Yet as the cancer progressed, the pain in his liver

became intense. We had two nurses in the daytime, but in the evenings Michael

and I were alone together. We had long talks. “Think how lucky we’ve

been,” He’d say. “How lucky we met. How lucky we’ve had all these

wonderful years together.” And he’d say, “Cindy, if I’m going to die,

it’s probably better if I die now than if I died in ten years. You’re still

young, and it’ll be easier for you to get on with your life.” I wanted to

scream when he said things like that, but I just smiled and passed on to the

next thing. I knew he was trying to soften the blow. As the weeks went by the

pains got worse, and we had to put him on morphine and percocet. He got a little

thinner, too, but he was never down to 90 pounds, like the tabloids said, and

thank God the chemo didn’t make his hair drop out. Even there, Michael turned

his anxiety into a joke. He said if he lost his hair they could put his picture

on the cover of Bowlers’ Journal. The sense of humor was there to the end, but

as he got weaker his sadness grew. I’d walk into the bedroom and find him

crying quietly. When I’d ask what was wrong, he’d say, “It’s not seeing

you again.” When the children came in, he’d look at them so long and so

intensely – as though trying to take in everything about them. He would touch

their hands and faces, and tears would fill his eyes. But he had no regrets, no

feeling he should have lived life differently. He’d done what he wanted to do

and done it with all his strength, and that was that. Finally the day came when

he said, “Cindy, I’m dying. I can feel it in my body. I’ve got a week to

live.” He was right. He died exactly one week later. All that last week I saw

him fading. Somehow the reporters knew and came swarming around like vultures.

It was a deathwatch. I was outraged and so was Michael. “What is this,” he

said, “some sort of frigging game?” On Sunday morning, June 30th,

I knew the end was near, so I called all his children and his closest friends,

and they came to the house. Michael was Michael. Very alert. Talking with

everybody and joking. Later in the day he began dozing, off and on. The pain got

worse, and we had to increase his morphine and percocet. The nurses said the end

could come at any time, so we stayed there with him through the afternoon and

into the night. Michael drifted into a dreamlike state, neither awake nor

asleep, and began talking in a rambling way. Then he started coughing up blood.

At about 11 o’clock, everybody went off to get some sleep. I stayed with him

through the night. In the morning everybody gathered around his bed again –

Jennifer and Sean were there too – and we were all crying because we knew it

was the end. Then all of a sudden Michael became completely alert, sat up,

looked around at all of us standing there and said, “Oh, hi guys.” And he

smiled and said, “I love you very much.” Everybody was startled and very

emotional. But pretty soon they said goodbye because Michael didn’t want a lot

of people watching him when he died. When I was there with him alone, we talked

a little and hugged. The he went back into the dreamlike state and began

rambling and waving his arms. I realized that he was directing a movie in his

mind. “Put a 50 over here,” he said – a 50 is a stage lamp. “Tell that

guy he’s lying the wrong way.” Then he started writing in the air, and a

minute later he sat up and actually pulled on a pair of imaginary boots. After

that he grabbed my blouse and tried to tie it in a bow. I told him to relax,

calm down, because his movements were getting frantic. I asked him, “Do you

know who I am?” He said, looking right at me, “Mm. Yeah.” And I said, “I

love you.” And he said, “I love you too.” Those were Michael’s last

words. He lay down and began breathing heavily. Pretty soon his breathing became

deeper and less frequent. I called the nurse, who came running in and put a

stethoscope to his chest. Michael took one last breath, and was gone. I just sat

there beside him. I was numb. I couldn’t believe what had just happened. I

don’t remember if I said anything. I just remember that I sat there. Ten

minutes, 15 minutes. Then I went downstairs and told everybody that Michael was

gone, and they came up to the bedroom again. All at once there was a terrible

roaring overhead. It was a helicopter from one of the television stations! I

couldn’t believe it. How dare they take this moment from us! Then the roaring

went away, and we all sat there with Michael a little while longer. Suddenly we

heard screaming. It was Jennifer, who  had run out of the house and climbed to

the top of our swing set, about 10 feet in the air. She was screaming and

screaming, “No! Not my daddy! I don’t want my daddy to die!” People tried

to pull her down, but I was calm – the way Michael was in a crisis. It was

almost as if I were Michael. “Let her be,” I said. “Let her get it out.”

Then I talked to her, and she came down, and soon she was sobbing quietly in my

arms. About an hour later the undertaker’s van arrived, and I went up to

Michael again – and I got a shock. There he lay in the same place, but he

looked like an entirely different person. Everything had been sucked out and he

was just an empty shell. And then they took him. I had always walked Michael out

to the car to say goodbye, so I had to go with him this one last time. It was

very hard. But I went with him to say goodbye.

had run out of the house and climbed to

the top of our swing set, about 10 feet in the air. She was screaming and

screaming, “No! Not my daddy! I don’t want my daddy to die!” People tried

to pull her down, but I was calm – the way Michael was in a crisis. It was

almost as if I were Michael. “Let her be,” I said. “Let her get it out.”

Then I talked to her, and she came down, and soon she was sobbing quietly in my

arms. About an hour later the undertaker’s van arrived, and I went up to

Michael again – and I got a shock. There he lay in the same place, but he

looked like an entirely different person. Everything had been sucked out and he

was just an empty shell. And then they took him. I had always walked Michael out

to the car to say goodbye, so I had to go with him this one last time. It was

very hard. But I went with him to say goodbye.

By Tom Gliatto, Kristina Johnson & Vicki Sheff (February 10 1992)

“We

miss everything about Dad,” says Leslie, 29, his daughter by Lynn, who is a

family therapist. “There isn’t a day goes by when I don’t think of him.”

A battler by nature, he fought his cancer on as many fronts as he could. He

underwent experimental chemotherapy and stuck to a “natural” regimen that

included a mostly vegetarian diet and acupuncture. “Every time I would call

him and say, ‘Hi, Dad, how are you doing?’” Leslie recalls, “it was

always, ‘I’m great. Everything is fine.’” Then came the devastating news

that the tumor in his pancreas had doubled in size in less than a month (the

disease had already spread to his liver). The signs of defeat became clear on

Father’s Day, June 16. “He had told me earlier that he knew he was dying,”

says Cindy. Then, that day, “he was in the family room and he needed help just

getting up the stairs with his portable oxygen tank,” she says. For the

children too, Father’s Day marked a turning point. “I’d usually go out and

get him something for tennis or sports,” says Leslie. But this year she bought

him Gatorade and slippers with little basketballs on the toes. (At the time

Michael had been watching the NBA play-offs.) Her sister Shawna, 20, a

college-sophomore, gave him silk pajamas. Says Leslie: “It was like, ‘What

can I give him that he’ll enjoy now?’” For Chris the difference had the

feel of a sea change. “I was the father and he was the son,” he says. “I

had to help him up the stairs. I am sad sometimes…” His voice breaks. “…

sad sometimes when I think that I never said, ‘Sorry.’” Leslie clutches

his hand. “it’s OK,” she says. Crying, Chris continues, “I never looked

at him and told him that I was sorry he was losing his life.” “In the last

month and a half, “ says Leslie, “you started to take your time with him

because you just knew. There was a longing in Dad’s eyes when he was watching

everyone.” In a sense he even peered at the Landons yet to come. When

daughter-in-law Sharee Landon, 27, Michael Jr.’s wife, was eight months into

her pregnancy, “Dad used to put his hand on her tummy,” says Leslie. “He

would close his eyes and go, ‘Aaaaaaah,’ as if he was loving the baby.”

“I remember being with him at Jennifer and Sean’s school,” says

Cindy. “It was PE time for Sean, and he came running over and said, ‘Hey,

Dad, watch me! I’m going to run my laps now.’ And I remember Michael looking

at him and shaking his head and starting to cry.” To prepare Jennifer and Sean

for his death, Michael and Cindy would read them a children’s book called

Butterflies. “Dad would explain that when he died, his body would be like the

cocoon,” says Leslie, “and his spirit would be like the butterfly, looking

down at his old existence.” “Dad always made us feel good about heaven,”

says Jennifer. “See, I like marshmallows, so he would say that I could eat as

many as I want in heaven.” At the end of June, a visiting nurse warned that

Landon – down 30 lbs. To a mere 135 and exhausted with pain – had at most a

day to live. Cindy called the kids back to the ranch to make their goodbyes.

They gathered in his bedroom and waited. “He was ready to go,” says Leslie.

“We told him, ‘Let go, Dad.’” “You could say a thousand goodbyes,”

says Chris, “and it would never be enough.” The older kids spent the night

camping out on sofas. Sean came downstairs at 2 in the morning, remembers

Leslie’s husband, Brian Matthews, 31. “First he told me, ‘My daddy isn’t

dead yet,’’ Brian says. “Then, ‘Daddy told me he could be anything he

wants in heaven.’ So I asked him what he wanted his daddy to be, and he said,

‘I’d like him to be a crab, so he can cut through the clouds and drop back

down and be with us.’” “He really showed us how to handle death,” says

adopted son Mark, 43, a grocery clerk and aspiring actor. “I’d want to go

with dignity, like he did.” That night, Cindy and Jennifer both  slept with an

article of Michael’s clothing. But, the Landon’s have learned, there’s no

real way to swaddle grief. “It comes in waves, and it will hit you when you

don’t expect it,” says Leslie. “A picture, a song, a movie.” Shawna will

be driving her car and just start crying. Chris had to walk out of a physiology

class during a discussion on euthanasia. Cindy has settled back into a daily

routine. It helps, she says, that Landon left her “some beautiful letters in a

little book. I read those quite often. They’re about how to remain strong and

solid.” At least, she says, “I can sleep now without waking and staring at

the ceiling, feeling alone.” She’s not alone this afternoon. Whichever way

Cindy looks, she can see Michael in his family. “There is so much of him in

all of us,” says Chris, turning to Leslie and suddenly grinning. “You can be

raunchy, and so was he,” he teases. “Dad loved to bring in fantasy play and

pretending, which is a lot of what we do with the little ones still,” says

Leslie. “There are games that I play with them that Dad taught Mike Jr. and me

when we were little – like African safari in the pool.” But, ultimately,

what Michael taught his family wasn’t just about playtime but about a whole

lifetime. “When Brian and I have kids,” says Leslie, “there’ll be so

much that we’ll teach them because of the love of my dad and our family.

We’re going to live life to the fullest, like Dad did.” After three hours of

sharing stories about Michael, the family almost seems to have conjured him into

their presence. “I think he protects this house,” says Cindy.

“Sometimes,” says Leslie, “I will go up and sit in his closet among his

clothes to feel closer to him.” “When I walk into the TV room,” says

Shawna, “that one chair that he always sat in reminds me of him. You can see

that tuft of brown hair.” “And he’s always roll his toes,” says Chris.

“You can almost hear his toes cracking when you go in there.” He pauses.

“When I used to think about death, I’d say, ‘I don’t want to die at

all!’ But now,” he says, “I say the worst that’s going to happen is that

I’ll see Dad again.” Leslie holds Chris’s hand. “I know,” she tells

him, “we are all going to be together again.”

slept with an

article of Michael’s clothing. But, the Landon’s have learned, there’s no

real way to swaddle grief. “It comes in waves, and it will hit you when you

don’t expect it,” says Leslie. “A picture, a song, a movie.” Shawna will

be driving her car and just start crying. Chris had to walk out of a physiology

class during a discussion on euthanasia. Cindy has settled back into a daily

routine. It helps, she says, that Landon left her “some beautiful letters in a

little book. I read those quite often. They’re about how to remain strong and

solid.” At least, she says, “I can sleep now without waking and staring at

the ceiling, feeling alone.” She’s not alone this afternoon. Whichever way

Cindy looks, she can see Michael in his family. “There is so much of him in

all of us,” says Chris, turning to Leslie and suddenly grinning. “You can be

raunchy, and so was he,” he teases. “Dad loved to bring in fantasy play and

pretending, which is a lot of what we do with the little ones still,” says

Leslie. “There are games that I play with them that Dad taught Mike Jr. and me

when we were little – like African safari in the pool.” But, ultimately,

what Michael taught his family wasn’t just about playtime but about a whole

lifetime. “When Brian and I have kids,” says Leslie, “there’ll be so

much that we’ll teach them because of the love of my dad and our family.

We’re going to live life to the fullest, like Dad did.” After three hours of

sharing stories about Michael, the family almost seems to have conjured him into

their presence. “I think he protects this house,” says Cindy.

“Sometimes,” says Leslie, “I will go up and sit in his closet among his

clothes to feel closer to him.” “When I walk into the TV room,” says

Shawna, “that one chair that he always sat in reminds me of him. You can see

that tuft of brown hair.” “And he’s always roll his toes,” says Chris.

“You can almost hear his toes cracking when you go in there.” He pauses.

“When I used to think about death, I’d say, ‘I don’t want to die at

all!’ But now,” he says, “I say the worst that’s going to happen is that

I’ll see Dad again.” Leslie holds Chris’s hand. “I know,” she tells

him, “we are all going to be together again.”

Michael Landon