Featured Author

William Edward Norris (1847-1925)

Born in Cavendish Square in the West End of London on November 18th, 1847, William Edward Norris was the son of Sir William Norris, Chief Justice of Ceylon [Sri Lanka], and Fearne, née Kinnear, a Scotswoman from Edinburgh. He was educated at Eton, trained in the law and then called to the Bar at the Inner Temple in 1874. However, he never actually practised the law having a small competency which allowed him to live until his writing began to bring in considerable returns.

Born in Cavendish Square in the West End of London on November 18th, 1847, William Edward Norris was the son of Sir William Norris, Chief Justice of Ceylon [Sri Lanka], and Fearne, née Kinnear, a Scotswoman from Edinburgh. He was educated at Eton, trained in the law and then called to the Bar at the Inner Temple in 1874. However, he never actually practised the law having a small competency which allowed him to live until his writing began to bring in considerable returns.

His writing career began with journalistic and periodical work before he published his first novel Heaps of Money in 1877. The book did not, however, "catch on", although the critic George Henry Lewes, George Eliot and Anthony Trollope predicted a brilliant career for the new writer.

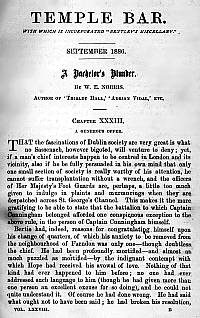

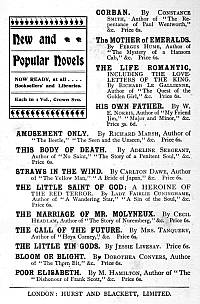

He tried again and succeeded this time with the vastly popular Mademoiselle De Mersac, published in 1880. Thereafter followed a long series of novels, many appearing in the Temple Bar and Cornhill magazines.

Reviewers often compared his easy-going style to William Thackeray's, finding parallels especially in Mademoiselle De Mersac, Marietta's Marriage, The Widower and Miss Wentworth's Idea, these novels providing, according to one reviewer in an introduction to a later edition of Miss Wentworth's Idea, "the same microscopic power of reading and reproducing the minutest shades of character...scintillating wit and wealth of epigrammatic apophthegms, united to a marvellous skill in interweaving the synchronous development of plot and character."

With the publication of Matthew Austin in 1894, he embarked upon his best period of work. However, his work always sold and he continued writing right up until his death. Norris wrote an enormous amount of fiction and yet he never rushed his work but always made sure sufficient time had been allowed for it to measure up to his own standard of excellence. His tales covered a wide variety of plots and settings: Mademoiselle De Mersac is partly set in Algiers, the hero of No New Thing is Anglo-Indian, a number of his heroes are writers, Major and Minor has a political setting, as does The Fight for the Crown which concerns a Conservative husband "burdened" with a Liberal wife, while Giles Ingilby concerns a noble, illegitimate young writer who goes off to fight in the Boer War. However, his most authentic descriptions and settings are those of society London life.

With the publication of Matthew Austin in 1894, he embarked upon his best period of work. However, his work always sold and he continued writing right up until his death. Norris wrote an enormous amount of fiction and yet he never rushed his work but always made sure sufficient time had been allowed for it to measure up to his own standard of excellence. His tales covered a wide variety of plots and settings: Mademoiselle De Mersac is partly set in Algiers, the hero of No New Thing is Anglo-Indian, a number of his heroes are writers, Major and Minor has a political setting, as does The Fight for the Crown which concerns a Conservative husband "burdened" with a Liberal wife, while Giles Ingilby concerns a noble, illegitimate young writer who goes off to fight in the Boer War. However, his most authentic descriptions and settings are those of society London life.

The Norris clan resided in Torquay, his father shown on the census as living at "Belvoir" in 1871, and twenty years later his widow is still living in the town at a residence called "Mount Stuart". She, herself, did not die until 1893, by which time she had reached the ripe old age of 87! By 1891, William Edward Norris was also living in Torquay at a place called "Underbank". By that time he was a widower with a 19 year old daughter, Edith Frances Fearne Norris, who was still unmarried and living at home ten years later. Even Norris's sister and her husband bought a large property there in 1906, called "Bishopstowe", and now the Palace Hotel.

Torquay and the Victorians

George Eliot visited Torquay in 1868 and writes to Miss Sara Hennell: "I don't know whether you have ever seen Torquay. It is pretty, but not comparable to Ilfracombe; and like all other easily accessible sea-places, it is sadly spoiled by wealth and fashion, which leaves no secluded walks, and tattoo all the hills with ugly patterns of roads and villa gardens. Our selfishness does not adapt itself well to these on-comings of the millennium." Later she writes to the publisher, John Blackwood, "This place is becoming a little London, or London suburb. Everywhere houses and streets are being built, and Babbicombe will soon be joined to Torquay." To Mrs Congreve she writes, "We find a few retired walks, and are the less discontented because the weather is perfect. I hope you are sharing the delights of sunshine and moonlight. There are no waves here, as you know; but under such skies as we are having, sameness is so beautiful that we find no fault...But we should not come again without special call, for in a few years all the hills will be parts of a London suburb." Once George Eliot has returned home she writes again to Mrs Congreve, "...we became deeply in love with Torquay in the daily heightening of spring beauties, and the glory of perpetual blue skies." (Cross, JW (ed.). George Eliot's Life as Related in her Letters and Journals. William Blackwood and Sons, 1885.)

"In 1869, Dickens made a reading tour of the west country, including Bath and Torquay. He describes Bath as, "a mouldy old roosting place that comes out mouldily as a let...I hate the sight of the bygone old Assembly Rooms and the Bath chairs trundling the dowagers about the streets...the whole place looks like a cemetery which the dead have succeeded in rising and taking. Having built streets of their old gravestones they wander about scantily trying to look alive - a dead failure." It was a relief to get to Torquay with its signs of spring and its plate-glass windows through which he commanded both sea and sunshine." (Pope-Hennessy, U. Charles Dickens 1812-1870. Chatto & Windus, 1945.)

The 1871 census delineates Torquay, along with Torbay as having the "charms of an Italian lake", whilst twenty years later a travel writer wrote of the "sad dignity of Torquay". By the end of the century, Torquay had become a popular resort among wealthy invalids suffering from a weak chest... (Horn, P. Pleasures and Pastimes in Victorian Britain. Sutton Publishing, 1999.) |

RL Wolff, who collected 42 titles by Norris talks of him as "an almost forgotten novelist who had a real power to depict fashionable people and their often serious predicaments." Late Victorians thought his fiction refreshingly "wholesome" and "well-bred". Termed the "novelist's novelist" because of the way he so aptly caught the temper of the time, his writing has been said to be that of "a cultured man of the world, one who is familiar with the best "sets", is on friendly terms with many notable people in society...[exhibiting] that easy savoir-faire which results from a life-long association with those to whom all social conventionalities are as familiar as their alphabet" (Introduction to Miss Wentworth's Idea).

William Edward Norris died at home in Torquay on the 20th November, 1925, his last novel Trevalion having been published that same year.

With especial thanks to my mum for researching the Census information

Biographical Bibliography

- Anonymous Introduction to Norris, WE. Miss Wentworth's Idea. London: The Caxton Publishing Company.

- http://www.crystalclouds.co.uk/search.php?option=ThisSource&searchbioid=2089

- http://www.e-travelguide.info/torquay/palacehotel/history.htm

- http://www.holmesautographs.com/cgi-bin/dha455.cgi/7277.html

- Sutherland, J. The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction. Singapore: Longman, 1990.

Here are a few quotes from some of WE Norris's fiction

Bianca (Stories by English authors - Italy. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1902)

Last of all, a poor little trembling figure, with pale face and eyes big with fright, crept in, and stood, hand on heart, a little in advance of the group. I slipped to her side, and offered her a chair, but she neither answered me nor noticed my presence. She was staring at her father as a bird stares at a snake, and seemed unable to realise anything except the terrible fact that he had followed and found her.

Miss Wentworth's Idea (1891)

"It is so hateful to know that at the very best one can only look forward to a few years of real life!" she exclaimed; "and to think that one is throwing away day after day of the precious time! If a woman is clever, if she can do something - such as writing or singing or painting - or even if she is a sort of pious enthusiast, like Muriel, it is different; but what is to become of a helpless ignoramus after her youth is over?"

A Bachelor's Blunder (1886)

Nature, as all the world knows, can be eloquent enough upon occasion; but those who wish to hear her true voice must approach her without preoccupations of their own; and as this is not a common condition among mortals, Nature for most of us only acts the part of an echo or a mirror. Beneath Hope's feet early violets were peeping out here and there; above her head the buds were tipped with green; in the pale sunshine and the mild air there was promise of spring. These things ought to have suggested to her that sorrow is no more eternal than joy, that fair weather must follow rain, and summer winter; and that there is always a good time coming for those who have the patience to wait for it; but what they actually did suggest to her was that every dog has his day, that new years are for new people, and that the past never returns.

Nature, as all the world knows, can be eloquent enough upon occasion; but those who wish to hear her true voice must approach her without preoccupations of their own; and as this is not a common condition among mortals, Nature for most of us only acts the part of an echo or a mirror. Beneath Hope's feet early violets were peeping out here and there; above her head the buds were tipped with green; in the pale sunshine and the mild air there was promise of spring. These things ought to have suggested to her that sorrow is no more eternal than joy, that fair weather must follow rain, and summer winter; and that there is always a good time coming for those who have the patience to wait for it; but what they actually did suggest to her was that every dog has his day, that new years are for new people, and that the past never returns.

The Rogue (1888)

Dreadful rumours about him reached Surrey. He had, it appeared, taken up the most extreme Radical, not to say Republican, ideas, and had proclaimed them in such a fashion as to have earned notoriety. Worse than this - supposing, for the sake of argument, that anything could be worse - he had become an avowed freethinker, if not an absolute atheist. Here was a pretty piece of business!

Some reviews of his Victorian novels

Misadventure (1890) NEWLY ADDED REVIEW!

ATALANTA Two novels of the season are Misadventure, by WE Norris (Spencer Blackett), and Lady Baby, by ED Gerard (Blackwood). They are both artistic in being admirably written and true to life, but they neither of them show their authors at their best. There is a certain commonplaceness about them which is unexpected and disappointing. The freshness of My Friend Jim is altogether lacking in Misadventure...Still, [the book is] much above the average standard, and will be read with pleasure by many. In Misadventure, Cicely is a delightful heroine, true to life in her girlish self-confidence, which yet has nothing unpleasant about it. She represents a very ordinary type of girl of the present day, for the time has quite gone by when timidity was considered a virtue. The incident which gives the title to the book is of a sensational nature, but Mr Norris possesses to perfection the art of never straining one's sensibilities too far. It might even be questioned whether he does not err a little on the other side. His books have a strange absence of passion, and his cynicism, though not unkindly, has the effect of continual cold water douches. Some critics have called Mr Norris our modern Thackeray, but surely in some respects the pupil has failed to follow in the steps of the master. The older writer does occasionally allow us glimpses of his great and tender heart; the younger one carries the art of repression too far.

His Grace (1892)

ATHENAEUM Mr Norris has drawn a really fine character in the Duke of Hurstbourne.

His Grace (1892)

ATHENAEUM Mr Norris has drawn a really fine character in the Duke of Hurstbourne.

The Despotic Lady and Others (1895)

SCOTSMAN A budget of good fiction of which no one will tire.

Clarissa Furiosa (1897)

THE WORLD As a story it is admirable, as a jeu d'esprit, it is capital, as a lay sermon studded with gems of wit and wisdom it is a model.

Some reviews of his later novels taken from PUNCH

The Triumphs of Sara (1920) I see that on the title-page of his latest story Mr W E Norris is credited with having already written two others (specified by name), etc. Much virtue in that "etc." I cannot therefore regard The Triumphs of Sara (HUTCHINSON) precisely as the work of a beginner, though it has a freshness and sense of enjoyment about it that might well belong to a first book rather than to - I doubt whether even Mr Norris himself could say offhand what its number is. Sara and her circle are eminently characteristic of their creator. You have here the same well-bred, well-to-do persons, pleasantly true to their decorous type, retaining always, despite modernity of clothes and circumstance, a gentle aroma of late Victorianism. Perhaps Sara is the most immediate of Mr Norris's heroines so far. Her money-bags had been filled in Manchester, and from time to time in her history you are reminded of this circumstance. It explains much; though hardly her marriage with Euan Leppington, whose attraction apparently lay in being one of the few males of her acquaintance whom Sara did not find it fatally easy to bring to heel. Anyhow, after marriage she quickly grew bored to death of him; so much so that it required an attempt (badly bungled) by another woman to get Euan to elope with her, and a providential collapse of the very unwilling Lothario, to bring about that happy ending that my experience of kind Mr Norris has taught me to expect. I may add that he has never done anything more quietly entertaining than the frustrated elopement; the luncheon scene at the Métropole, Brighton, between the angry but amused Sara and a husband incapacitated by rage, remorse and chill, is an especially well-handled little comedy of manners. (Punch, Vol. CLVIII, April 28, 1920)

Next of Kin (1923) It may seem strange now to recall that there was once a time (somewhere in the early 'eighties) when it was a matter for serious discussion in publishers' offices whether Mr Thomas Hardy or Mr W E Norris was the more likely to be first past the post in the race for fame. Nowadays, perhaps, we are inclined to rate the author of Clarissa Furiosa and My Friend Jim less highly than is altogether just. Something more than forty-five years have passed since this good craftsman published his first story, and Next of Kin (HUTCHINSON) shows little sign of weariness or loss of skill. It is, like most of his novels, thoroughly pleasant reading, in which the reader is subjected to no undue emotional stress. In a sense Mr Norris might be called the W D Howells of this country. He possesses a good prose style, a wide range of observation, the power of making his characters lifelike and natural, and a strong objection to violent action. I like the noble family into which young Brinley, the demobilised New Zealander, finds himself introduced as prospective heir to the title. But I am not quite so sure about the wayward Evie and her surprising marriage; and I cannot think the scene in which her very unpleasant husband breaks his neck rings altogether true. That is the worst of painting in a studiously quiet key. Mr Howells (irritated by accusations of lack of action) also introduced a railway accident into one of his novels, and the effect was as though he had brought on an earthquake. But Next of Kin is a book that deserves to be read - perhaps more than once.(Punch, Vol. CLXIV, March 28, 1923)

Next of Kin (1923) It may seem strange now to recall that there was once a time (somewhere in the early 'eighties) when it was a matter for serious discussion in publishers' offices whether Mr Thomas Hardy or Mr W E Norris was the more likely to be first past the post in the race for fame. Nowadays, perhaps, we are inclined to rate the author of Clarissa Furiosa and My Friend Jim less highly than is altogether just. Something more than forty-five years have passed since this good craftsman published his first story, and Next of Kin (HUTCHINSON) shows little sign of weariness or loss of skill. It is, like most of his novels, thoroughly pleasant reading, in which the reader is subjected to no undue emotional stress. In a sense Mr Norris might be called the W D Howells of this country. He possesses a good prose style, a wide range of observation, the power of making his characters lifelike and natural, and a strong objection to violent action. I like the noble family into which young Brinley, the demobilised New Zealander, finds himself introduced as prospective heir to the title. But I am not quite so sure about the wayward Evie and her surprising marriage; and I cannot think the scene in which her very unpleasant husband breaks his neck rings altogether true. That is the worst of painting in a studiously quiet key. Mr Howells (irritated by accusations of lack of action) also introduced a railway accident into one of his novels, and the effect was as though he had brought on an earthquake. But Next of Kin is a book that deserves to be read - perhaps more than once.(Punch, Vol. CLXIV, March 28, 1923)

The Conscience of Gavin Blane (1924) It seems almost incredible that Mr W E Norris should have published novels in the 'seventies. Yet so it is. While Mr Thomas Hardy was bringing out The Hand of Ethelberta and The Return of the Native, Mr Norris was already writing Heaps of Money and Mademoiselle de Mersac. There were then, by the way, certain publishing houses that preferred to risk their money on the second writer; there were even critics who considered that he would outlast the historian of Wessex. However that may be, Mr Norris remains most remarkably readable. He has acquired insensibly the modern touch, the modern way of handling his subjects. There is nothing in his recent novels that carries us back at all to the old days of three-volumed fiction. I think The Conscience of Gavin Blane (HUTCHINSON) as good as anything of his I have read for a very long time. It is surprisingly fresh. Gavin, of course, is rather ridiculously Quixotic in his ideas; but Quixotes still exist even in these days, and we have the satisfaction of feeling that his scruples about accepting an inheritance enable him at once to escape marrying a girl who would certainly have made him miserable and to discover wherein his own strength lies as a worker. All the characters in this natural story are interesting and well drawn. Una Lisle is an excellent presentment of a certain type of modern girl. Uncle Paul, the wealthy black sheep of the Blane family, who first disinherits his scoundrel son and then relents when it is, legally speaking, too late, sticks in the mind with the rest of his remarkable household. And Gavin himself is eminently likeable. In fine, a very good Norris indeed.(Punch, Vol. CLXVI, March 19, 1924)

Incidentally...

He was responsible for the epigram:

If you your lips would keep from slips,

Five things observe with care;

To whom you speak, of whom you speak,

And how, and when, and where.

I would love to read the short story Her Ladyship's Veil by WE Norris

Click here to see a list of his works

HOME

See other featured authors: Mrs George Linnaeus Banks, Sir Walter Besant, Rosa Nouchette Carey, Dutton Cook, Dinah Craik, Sarah Doudney, Ellen Thorneycroft Fowler, Mary E Hullah, Edna Lyall, Isabella Fyvie Mayo, GB Stuart, CEC Weigall.

Born in Cavendish Square in the West End of London on November 18th, 1847, William Edward Norris was the son of Sir William Norris, Chief Justice of Ceylon [Sri Lanka], and Fearne, née Kinnear, a Scotswoman from Edinburgh. He was educated at Eton, trained in the law and then called to the Bar at the Inner Temple in 1874. However, he never actually practised the law having a small competency which allowed him to live until his writing began to bring in considerable returns.

Born in Cavendish Square in the West End of London on November 18th, 1847, William Edward Norris was the son of Sir William Norris, Chief Justice of Ceylon [Sri Lanka], and Fearne, née Kinnear, a Scotswoman from Edinburgh. He was educated at Eton, trained in the law and then called to the Bar at the Inner Temple in 1874. However, he never actually practised the law having a small competency which allowed him to live until his writing began to bring in considerable returns. With the publication of Matthew Austin in 1894, he embarked upon his best period of work. However, his work always sold and he continued writing right up until his death. Norris wrote an enormous amount of fiction and yet he never rushed his work but always made sure sufficient time had been allowed for it to measure up to his own standard of excellence. His tales covered a wide variety of plots and settings: Mademoiselle De Mersac is partly set in Algiers, the hero of No New Thing is Anglo-Indian, a number of his heroes are writers, Major and Minor has a political setting, as does The Fight for the Crown which concerns a Conservative husband "burdened" with a Liberal wife, while Giles Ingilby concerns a noble, illegitimate young writer who goes off to fight in the Boer War. However, his most authentic descriptions and settings are those of society London life.

With the publication of Matthew Austin in 1894, he embarked upon his best period of work. However, his work always sold and he continued writing right up until his death. Norris wrote an enormous amount of fiction and yet he never rushed his work but always made sure sufficient time had been allowed for it to measure up to his own standard of excellence. His tales covered a wide variety of plots and settings: Mademoiselle De Mersac is partly set in Algiers, the hero of No New Thing is Anglo-Indian, a number of his heroes are writers, Major and Minor has a political setting, as does The Fight for the Crown which concerns a Conservative husband "burdened" with a Liberal wife, while Giles Ingilby concerns a noble, illegitimate young writer who goes off to fight in the Boer War. However, his most authentic descriptions and settings are those of society London life. Nature, as all the world knows, can be eloquent enough upon occasion; but those who wish to hear her true voice must approach her without preoccupations of their own; and as this is not a common condition among mortals, Nature for most of us only acts the part of an echo or a mirror. Beneath Hope's feet early violets were peeping out here and there; above her head the buds were tipped with green; in the pale sunshine and the mild air there was promise of spring. These things ought to have suggested to her that sorrow is no more eternal than joy, that fair weather must follow rain, and summer winter; and that there is always a good time coming for those who have the patience to wait for it; but what they actually did suggest to her was that every dog has his day, that new years are for new people, and that the past never returns.

Nature, as all the world knows, can be eloquent enough upon occasion; but those who wish to hear her true voice must approach her without preoccupations of their own; and as this is not a common condition among mortals, Nature for most of us only acts the part of an echo or a mirror. Beneath Hope's feet early violets were peeping out here and there; above her head the buds were tipped with green; in the pale sunshine and the mild air there was promise of spring. These things ought to have suggested to her that sorrow is no more eternal than joy, that fair weather must follow rain, and summer winter; and that there is always a good time coming for those who have the patience to wait for it; but what they actually did suggest to her was that every dog has his day, that new years are for new people, and that the past never returns. Next of Kin (1923) It may seem strange now to recall that there was once a time (somewhere in the early 'eighties) when it was a matter for serious discussion in publishers' offices whether Mr Thomas Hardy or Mr W E Norris was the more likely to be first past the post in the race for fame. Nowadays, perhaps, we are inclined to rate the author of Clarissa Furiosa and My Friend Jim less highly than is altogether just. Something more than forty-five years have passed since this good craftsman published his first story, and Next of Kin (HUTCHINSON) shows little sign of weariness or loss of skill. It is, like most of his novels, thoroughly pleasant reading, in which the reader is subjected to no undue emotional stress. In a sense Mr Norris might be called the W D Howells of this country. He possesses a good prose style, a wide range of observation, the power of making his characters lifelike and natural, and a strong objection to violent action. I like the noble family into which young Brinley, the demobilised New Zealander, finds himself introduced as prospective heir to the title. But I am not quite so sure about the wayward Evie and her surprising marriage; and I cannot think the scene in which her very unpleasant husband breaks his neck rings altogether true. That is the worst of painting in a studiously quiet key. Mr Howells (irritated by accusations of lack of action) also introduced a railway accident into one of his novels, and the effect was as though he had brought on an earthquake. But Next of Kin is a book that deserves to be read - perhaps more than once.(Punch, Vol. CLXIV, March 28, 1923)

Next of Kin (1923) It may seem strange now to recall that there was once a time (somewhere in the early 'eighties) when it was a matter for serious discussion in publishers' offices whether Mr Thomas Hardy or Mr W E Norris was the more likely to be first past the post in the race for fame. Nowadays, perhaps, we are inclined to rate the author of Clarissa Furiosa and My Friend Jim less highly than is altogether just. Something more than forty-five years have passed since this good craftsman published his first story, and Next of Kin (HUTCHINSON) shows little sign of weariness or loss of skill. It is, like most of his novels, thoroughly pleasant reading, in which the reader is subjected to no undue emotional stress. In a sense Mr Norris might be called the W D Howells of this country. He possesses a good prose style, a wide range of observation, the power of making his characters lifelike and natural, and a strong objection to violent action. I like the noble family into which young Brinley, the demobilised New Zealander, finds himself introduced as prospective heir to the title. But I am not quite so sure about the wayward Evie and her surprising marriage; and I cannot think the scene in which her very unpleasant husband breaks his neck rings altogether true. That is the worst of painting in a studiously quiet key. Mr Howells (irritated by accusations of lack of action) also introduced a railway accident into one of his novels, and the effect was as though he had brought on an earthquake. But Next of Kin is a book that deserves to be read - perhaps more than once.(Punch, Vol. CLXIV, March 28, 1923)