t is my last day in London," said Alice Harper to herself.

t is my last day in London," said Alice Harper to herself. t is my last day in London," said Alice Harper to herself.

t is my last day in London," said Alice Harper to herself.

The "last day" was a Sunday at the end of July, and Alice's box was packed, and ready for travelling. She had attended service that morning in a beautiful church, where she had often gained strength and comfort in her weariness; and the music was still echoing in her ears when she turned into Bruton Street. Wherever she went, she knew that she should hear that music still.

The smart people were all hurrying out of town as fast as they could go. But Miss de Vigny was a very dignified little lady who never cared to hurry herself in the least. She always went away on the first of August, and could not be moved sooner or later. So that when Alice went into her house, she found her friend sitting in her old chair near the window with an open book on her lap.

Miss de Vigny had always liked Alice Harper. She had watched the girl through the season that preceded the sudden change in her lot, and had thought her distinctly genuine and courageous. She did not guess how soon that quality of courage would be called into play; but when the crash came, she was not surprised that Alice bore up bravely under the blow.

Miss de Vigny had always liked Alice Harper. She had watched the girl through the season that preceded the sudden change in her lot, and had thought her distinctly genuine and courageous. She did not guess how soon that quality of courage would be called into play; but when the crash came, she was not surprised that Alice bore up bravely under the blow.

One morning the daily papers announced the suicide of Mr Harper, the well-known promoter of companies. His daughter, left quite alone in the world, gathered together her few possessions, and quietly vanished from the eyes of society. Only two or three persons knew what had become of her, or what she was doing, and Miss de Vigny was one of them.

She had found out that Alice was going to be a dressmaker, and take care of herself in future in her own way. Miss de Vigny met her one day in a side street in the West-end, dressed in plain black, and carrying a brown-paper parcel. She did not avoid the little maiden-lady as she would have avoided some of her former friends. She stopped and accepted the hand that was held out so readily.

"I shall be eighteen months in learning my business," she said. "After that I must work six months longer as 'an improver.' And when I have thoroughly mastered the art, or trade, or anything that you like to call it, I mean to go away, and set up in the country."

"Quite in the country?" Miss de Vigny asked.

"Quite in the country," Alice replied. "I shall learn what London can teach me, and leave it with a glad heart. Mind, I am sure that I could not learn properly anywhere else. But I shall rejoice when I am free to go."

"When the time comes, perhaps I can help you," Mary de Vigny said. "Meanwhile, let me see you sometimes. Come and spend next Sunday with me in Bruton Street."

"But I do not want to meet people," said Alice, flushing deeply.

"My dear, I do not want you to meet people. It will do me good to have you all to myself. I have never been a society woman; the smart people don't find me at all amusing, I believe. I am dowdy, and I do not know any good stories. Pray come."

So Alice went. Miss de Vigny was rather dowdy, and she did not know any good stories; but she knew other things that are better worth knowing. She knew how to guide a sad soul into the true way of peace. She was neither a rich woman, nor a smart woman; but she lived a life worthy of her faith, and was a light to direct others to the road that led to rest.

From Mary de Vigny's house, Alice went to Mary de Vigny's church close by. And so the two toilsome years in London were sweetened and cheered; and if her outer life was hard and painful, her inner life became peaceful and fair. The time of release had come at last, and it was Mary who had found her a new home in the country.

Miss de Vigny's room was cooler than most rooms in London, and when you went in you felt you had entered into an atmosphere of contentment. There were always flowers here; to-day Alice's eyes rested gratefully on a big bunch of mignonette and some graceful feathery grasses. Mary greeted her with genuine affection, and pointed to the nosegay.

"Only think what it will be," said she, "to have your fill of flowers!"

"Oh, I have been trying to realise the delight in store for me!" Alice cried. "My poor father never cared for the country in the very least. He always bustled me about to fashionable watering-places in the summer. If my mother had lived, life would have been different for him and for me."

She sighed; but Mary spoke cheerfully.

"We must let all the 'ifs' alone, Alice," she said. "It is better to leave 'ifs' and 'might-have-beens' lying by the wayside if we want to get on upon our journey. I know how prone we are to stop, and pick up useless regrets; it has been an old folly of my own."

They had tea together, with the mignonette on the table between them. Miss de Vigny said it was like a festival, but she thought Alice looked tired and worn.

"I don't think you could have toiled on much longer," she remarked. "It has been a weary time, my child."

"You have brightened it," said Alice gratefully. "Everybody else has forgotten me, and you know I wished to be forgotten."

"Here and there one remembers you," said Mary, looking at her with observant eyes. "Only yesterday, in this very street, I met someone who asked what had become of you."

"I hope you did not tell!" Alice cried.

"I told very little. I merely said that you were living, and working for yourself. It was Mr Cardigan who asked for you."

Alice's mouth took a scornful curve.

"I do not like him," said she. "I detest rich men."

Miss de Vigny shook her head in reproof.

"That is rather a hard saying, my dear. For my own part, I think well of Robert Cardigan. He is natural - refreshingly natural, and I fancy he wants to know what to do with his money. After all, that money came to him in an honest way from a relation who died abroad; I do not see why it should not wear well."

"Perhaps I am prejudiced," said Alice colouring. "I have not liked what I have seen of rich men. Most of them always wanted to be richer still, and hovered round my father to be instructed in investments. Mr Cardigan only came into this fortune just before the blow fell upon me. But I thought he was like all the rest."

Miss de Vigny dropped the subject. She was not a woman of many words, and generally knew when to hold her peace.

Alice walked to church with her a little later, looking very stately and erect beside her small companion. People had always regarded Alice Harper as a proud girl; and there was something in her bearing which certainly suggested pride. Plain clothes only accentuated her air of distinction. And this evening, although she was very pale, and there were dark shadows beneath her grey eyes, she was more beautiful than she had ever been in the days of prosperity.

Adversity either disfigures or beautifies. There are certain full-fed, insolently-prosperous girls who would be enormously improved by sorrow. Many a plain face has been made lovely by the chastening of the spirit; and Miss de Vigny, who did not possess a single good feature, had a countenance on which, at the first glance, you could read the sweet record of inward peace. She had suffered meekly, and had come out of the strife into the rest.

Afterwards, when they parted at the door in Bruton Street, Mary said "good-bye" very tenderly to her friend. She knew that she would miss Alice when she came back to town in the autumn. But above all things she desired that the girl might have peace after the weary struggle to learn her business. One had only to look at Alice to see that she was a woman who would do what she meant to do. But these resolute people do not succeed without paying the cost of their success.

"I know you will be happy at Swallow's Nest," Mary said confidently. "I have often told you how long Mrs Bower lived with my mother, and how good and faithful she was. Some day I shall run down to the farm and see you all. You will write soon, dear, will you not?"

Alice did not find it very easy to answer. Her grey eyes were full of tears. She looked earnestly at Miss de Vigny for a moment, and went her way.

There was something dream-like about the London streets in the evening light. And Alice, walking back to the home which had sheltered her for two years, felt as if she, herself, were someone who had been living in a dream.

She thought of the only child of the rich man, brought up in a luxurious home, but always pining for the mother who had been early lost. She saw again those sunny heights of womanhood which the child's eyes had seen afar off. How bright they were then! Something of the old splendour lingered about that cloudland still, although the girl had become a sorrowful, hardworking woman. She smiled pityingly at the child who had always dreamed of doing beautiful things, and making everybody happy when she grew up! And yet, perhaps the pity was wasted after all. There are the elements of true happiness in many an unselfish dream. We cannot tell how much we have helped others by the loving desires that we could not shape into deeds. We do not see what our good angels are doing even with the thoughts of our hearts, when they are sweet and true.

And then came a sudden remembrance of the men who had come to her father's house in Park Lane - men who had shown by their faces and by their words that they existed only for self-pleasing. The quiet girl, with her own aims and ideals, had inwardly despised them all. Robert Cardigan had been, perhaps, a little better than the rest. She could recall certain looks and tones of his that had seemed real. He had even listened, with some interest, to those schemes for helping humanity which she had spoken of, once or twice, in his hearing. Well, the power that she had longed for had come to him; but it was doubtful if he would use it as she would have done.

The child and the girl had both passed away; Alice Harper, dressmaker, was walking through these West End streets to the home for working women which had been her refuge for two long years. And Alice Harper, dressmaker, was going to leave London tomorrow to live in the country.

She had never seen Mrs Bower, but she knew her perfectly by description. Mrs Bower was the wife of a farmer; they had two daughters who wanted to learn dressmaking; and there was a good opening for business in their neighbourhood. Miss de Vigny had advised Alice to go to Swallow's Nest.

"If you get tired of the country you can leave it," she had said. "But you have an instinctive longing for woods and fields and fresh air, and you are sorely in need of all these blessings."

The big house was generally quiet on a Sunday evening. It was sultry weather, and all the windows were opened wide. Alice caught a glimpse of the new moon above the house-tops as she ran upstairs. It hung faint and golden over the crowded roofs, in a sky touched with pale crimson, and dim with mist.

"I shall see it to-morrow above the woods," she thought with a sudden gladness.

She took off her hat and coat in her cubicle, and ran down to supper in her muslin blouse and tweed skirt. Not a single person in that full house was acquainted with her real history. She had never talked of bygone days and lamented her vanished prosperity. She wore no jewels; her watch was the sole relic of the past that could ever be seen. One or two had remarked that it was a very beautiful watch, and she had simply said that it was a gift from someone who was dead.

But in spite of a strong natural reserve she had made many friends. Living here, a poor woman among the poor, she had learnt that one must give love if one cannot give money.

"So you are going to leave us, Miss Harper," said a young girl who sat beside her at supper. "You will be missed for many a day. There are kindnesses that we never forget."

"Ah, if only I could have been more helpful," Alice sighed.

"You don't know how much you have helped," the other answered. "People may give gold, and it may go just as far as gold can. That is a long way, some will say. Well, so it is, but even the long way has a limit. There is only one thing that is not hindered by any limit at all. It flies on, far, far beyond Time, and right into Eternity. It is Love."

Alice looked attentively at the girl for a moment. She was a puny young woman with round shoulders and a narrow chest. Her skin was very fair, and she had the large luminous eyes which often indicate consumption.

"How did you learn so much, Miss Dayne?" asked she with a smile.

"Just by watching life," was the reply. "I do not think that we shall ever meet here again. I am going a longer journey than you are. And yet, who knows? Perhaps it may not be so very far."

Alice had arranged to start on Monday by a very early train. She left the house before any of the other women had come downstairs. Her box was in the hall; she had supplied herself with some sandwiches, and could have a cup of tea at the station. So she was driven through the streets before the shops were open, or London had shaken off such sleep as it can get. She reached Waterloo in time to drink her tea, and secure a comfortable corner in a third-class carriage.

When the train began to move out of the station she was still thinking of herself as Alice Harper, the dressmaker, going to start afresh in a new sphere. The former Alice was merely the girl of the dream.

She smiled, rather a forlorn little smile, when she called up a vision of the dream - Alice, travelling first-class, and wearing a lovely, grey costume, as costly and as daintily simple as it could possibly be. The dressmaker was arrayed in a coat and skirt of pepper-and-salt tweed which would stand any amount of wear and tear, and a pink calico shirt. Her gloves were carefully mended; a very serviceable umbrella and sunshade were strapped up with a plain waterproof cloak; she had none of those charming superfluities which a well-to-do woman seldom goes without. And yet it was a peaceful face that was shaded by the sailor hat; and as the train rushed on into the sweet, green country her eyes grew very bright.

"I am going where I shall get lots of pleasant things without paying for them," she said to herself. "In London you must pay your penny for the simplest flower that grows. Ah, the good God must have thought of the poor when He purpled the wild land with the glory of heather!"

"I have never been so happy before in all my life!" Alice said.

All around her was the common, seldom-heeded loveliness of an English lane in August. A long colonnade of oaks barred the way with shadows. The bindweed hung its garlands of little leafy hearts across the hedges. The bramble showed an abundance of green fruit which would swell and turn black by-and-by; and among the ground-ivy and strawberry leaves a few poison-berries shone out brightly, like witches' jewels. This was the grassy road leading to Swallow's Nest, and Alice had loved it from the very first day when she came here with her luggage, just a fortnight ago.

The farmhouse was very old, and no one could ever remember a summer when the swallows had not built there. It was a place that did not change as other places do. The birds always knew that they should find a convenient shelter just under the roof of the ample porch. No matter how far they had flown, no matter what fairer scenes they had visited, they never failed to come back to this quiet English home.

Not only in the porch did they build, but under the eaves, in little nooks about the roof, in every place which would hold their funny nests, made of little lumps of clay artistically massed together. The house was haunted by shrill notes and glancing wings. You could not pass through the door without sending a swallow flying out into the sunlight.

They were not content merely with the outside of the old dwelling. Very often they flashed in through an open window and flew in circles round the room, chattering as they flew. Alice sometimes wished that she could understand that rapid bird-language, so full of hidden meanings and quick changes of expression. What a companion a swallow might be, if we could but interpret the wisdom that he brings!

Alice and her pupils were already getting plenty of work to do. She had dropped down, quite happily, into the middle of a very pleasant family who were all pulling one way - and that was a good way. But it took all her own good sense, and the judicious hints of Mrs Bower, to reconcile her to making up the hideous materials brought by the surrounding neighbours. The crude reds and greens, the staring blues and yellows, filled her with disgust. And as she sauntered through the lane on a golden afternoon, she wondered why people did not study colour in the hedges.

Here was the delicate lilac of the wild geranium; here were the beautiful shades of olive and brown and buff so dear to an artist's eyes. Alice enjoyed them all; and drew in deep breaths of sweet-scented air, with a pitying remembrance of those who lived in the sickening atmosphere of heated London.

So the peaceful days went and came. Miss Harper's services became more and more in request, and by the time that the blackberries were ripe, she was employed by the "best families" in the neighbourhood.

One day a young lady trundled up to the gate in a pretty little pony-cart; and Ethel Bower, catching a glimpse of her through the open window, said in a low tone that it was Mrs Monteagle.

"Our squire's wife," she added, as she went to the door. Alice, sitting among silks and cashmeres and tweeds, did not feel any special interest in the new-comer. But at the first sight of Mrs Monteagle's pretty, piquant little face, she had a flash of remembrance.

The lady made just the slightest pause before speaking. Miss Harper, however, met her with grave politeness and an impassive face. So Mrs Monteagle plunged into business at once, and explained that she wanted a really pretty tea-gown.

She had brought a parcel of soft rich silk, and plenty of delicate lace. Miss Harper examined and approved, and promised to execute the order in a week.

"Letty Foster always had good taste," she thought, as the cart trundled away, "And so she has married 'our squire.' Well, she will find that I, at any rate, can be utterly oblivious of our meetings elsewhere. It is quite a pleasure to make up such lovely silk as this; and I am really very much obliged to Mrs Letty."

On the evening of the same day "Mrs Letty" went to the door of her husband's dressing-room, just before dinner, and told him that she had made a discovery.

"Well, what have you discovered?" asked he. "Upon my word, I wish it was a pot of gold."

"It's not a pot of gold. It's a former acquaintance under the guise of a dressmaker!" cried Mrs Monteagle gleefully. "It's Alice Harper, who used to live in Park Lane - Alice Harper, the daughter of that old company man who blew out his brains. Isn't it funny?"

"It doesn't strike me that it's funny when a man blows out his brains," said the squire. "I wish he hadn't done it. If he had lived I might have made him useful."

"What could he have done for you, Gerald?" asked Mrs Monteagle, opening her eyes.

They stood fronting each other alone for a minute or two. She noticed that he had some deep lines on his face, and looked worn.

"Well, he could have got some money for me," said he simply. "I say, Letty, I don't want to bother you, but we must contrive to pull in a bit, Cardigan is coming here tomorrow. If I can, I shall get him to buy Swallow's Nest."

"Oh, the charming old farm! That's where Miss Harper is living," said his wife. "I am sorry that you must part with it. Yes, I will be very economical, dear. Mr Cardigan is awfully rich, they say."

Robert Cardigan alighted at the little rural station in rather a gloomy mood. It is a truism that rich men are by no means the most cheerful; and Robert, perhaps, was feeling the embarrassment of wealth.

The squire's dog-cart was waiting, and, as he drove through the autumn lanes, the beauty of the country stole over him like a charm. He wished all at once that he could be a boy again, and go a-nutting in the deep woods. Monteagle, he thought, was a lucky man to own these acres of woodland, and these beautiful fields stretching away to ranges of quiet hills. It was the kind of country that he liked; neither wild nor grand, but just simply pastoral and sweet.

He hoped that he should not find a big house-party. Miss de Vigny had called him refreshingly natural, and it was certain that vanity was not his principal fault. But a man with many thousands a year is never left long in ignorance of his own importance. Cardigan had been hunted from pillar to post, pelted with showers of invitations, courted discreetly and indiscreetly, until he was weary of a life so over-sweet. What would he not have given for a true friend?

There was a certain face which rose up often in his memory; a girl's face, calm, and a little proud, with serious grey eyes. That girl had been always devising impossible plans for doing good to others. He had smiled while he listened to her earnest talk, and wondered how such notions could have got into the head of Harper's daughter.

He did not know what had become of her. Mary de Vigny seemed to know, but had not been disposed to say much. He wished now that he had plied the little maiden lady with questions. He would call on her, he thought, when he returned to town, and plainly ask her to tell him all about that girl.

To his relief he found that there were only a few people at Courland Hall.

The squire had been married only twelve months. He had chosen for a wife a thoughtless good-natured girl, with very little money. Letty had always been accustomed to rely to a great extent on her own brains when she was in want of a little extra finery. She had contrived to make a charming appearance on a small allowance. To marry Gerald Monteagle was, to her fancy, like coming into the possession of a gold mine.

She had begun by spending freely. Those few words, spoken in the dressing-room, had been the first hint of tightening the purse-strings. They had sobered her spirit, and brought her closer to her husband than she had ever been before.

No wedded pair can ever be perfectly united until they have passed out of the sunshine into the shade. When the sun goes down behind a bank of clouds, and a chill wind sighs across the roses, then the bride becomes the wife in real earnest, and creeps nearer to her husband's side. It is then that he discovers what a deep well of tenderness lies in the heart of the girl who was perhaps lightly wooed and easily won.

Letty's gaiety was just tinged with gravity, and Cardigan, who had thought to find her a mere trifler, liked her better than he had expected, and was ready to be a friend to the young couple. He went into the woods with the squire, and the two men grew intimate.

"I wouldn't part with a foot of my land if it could be helped," Monteagle confessed. "But times are bad, and I must let Swallow's Nest go."

"It's a beautiful country," said Cardigan.

"Swallow's Nest is one of our prettiest bits," the squire said. "Just come and have a look at it. You can get a good view from the top of that field."

The old farm-house was bathed in the mellow light of the October afternoon. A few late roses still lingered in the front garden, and clambered up the rough flint walls; and there were geraniums blooming on the ledges inside the porch. It was not a big house, by any means, and the latticed windows were small and mean. Looking down upon this dwelling, Cardigan only thought that it was not pretty enough to be set in such a lovely spot. It never occurred to him just then that it was a home.

"Upon my word, Monteagle," said he suddenly, "I'm half inclined to buy the place myself. It would be easy enough to pull down that ugly little barn, and put up something really picturesque."

"Quite easy," said the squire.

"I know exactly the sort of thing I should like to build there," Cardigan went on. "Nothing showy, you understand, but something that would harmonise with the surroundings. Well, Monteagle, we must talk the matter over."

And the matter was talked over, and settled after dinner that very evening. Cardigan was not the man to worry about the price. The squire went up to his room that night with a lightened heart.

"I am sorry that the Bowers will have to turn out; that's the worst part of it," he said to his wife.

"Mrs Bower and the girls are so nice," Letty answered. "And, oh, Alice Harper lives there, I was forgetting that! But they will easily find a place somewhere else, darling. It is such a relief to me to see that you have cheered up."

"The money will just set me straight, Letty," said he.

Ill news generally flies apace. The Monteagles' butler was one of Bower's old friends. A few days after the arrangement was made the farmer came in one evening with a down-cast face.

"I couldn't have thought the squire would have done such a thing!" he cried. "He's sold the old place right over our heads! My father lived here, and my grandfather, and my great-grandfather. And now it's going to be pulled down, and a new place'll be stuck up to please a chap who comes from nobody knows where!"

Little Milly was listening with all her ears. She burst out crying, and ran at once into the next room to tell the doleful tidings to her sisters and Miss Harper.

Ethel Bower lifted her fair Madonna face from her work, and stared at the child in surprise. Ada, dark-eyed and pretty, tossed her head and said she didn't believe a word of it. And Alice Harper, putting the finishing touches to Mrs Monteagle's tea-gown, said very earnestly that she hoped it was not true. But before she went to bed that night she learnt that it was really true.

With a sad heart she went to her latticed window and leaned out into the soft darkness of the autumn night. The air was full of those sweet earthy scents that breathed of home and rest. Under this peaceful roof she had found a safe refuge from the storms of life. A refuge, and something more. True hearts that turned to her for helpful love; young spirits trusting to her stronger spirit for that uplifting that she could give them. Simple souls, clinging in human fashion to the old walls that had sheltered them so long - must they be driven out to seek a new dwelling at a rich man's will?

With a sad heart she went to her latticed window and leaned out into the soft darkness of the autumn night. The air was full of those sweet earthy scents that breathed of home and rest. Under this peaceful roof she had found a safe refuge from the storms of life. A refuge, and something more. True hearts that turned to her for helpful love; young spirits trusting to her stronger spirit for that uplifting that she could give them. Simple souls, clinging in human fashion to the old walls that had sheltered them so long - must they be driven out to seek a new dwelling at a rich man's will?

Then Alice knelt down and prayed with all her strength, lifting up her face to the eternal stars above her. She prayed that she, who had come a stranger to this dear old house, might bring a blessing under its protecting roof. Lonely and sad, with a scanty purse and a tired body, she had come to dwell with these people, to work with them, and share their life. And He who had led her there would surely help her to assist them in their hour of sorrow and need.

She rose early next morning, and went downstairs to see sad faces at the breakfast-table. Just before the farmer went out to his daily tasks, it came into her head to ask him a question.

"Mr Bower," she said, "did you hear the name of the person who has bought your farm?"

"Yes," he answered: "but it is a name not known to any of us. It's Cardigan. He's a young man, I'm told, who has come into a lot of money. The squire asked him to stay at the Hall, and it seems that he's taking a mighty fancy to the neighbourhood."

Alice's heart began to throb fast. If Robert Cardigan were the man that Mary de Vigny thought him, it might be very easy to move his heart. But when, and in what manner, could this be done?

Her brain was still busy with these thoughts while she was carefully folding up the tea-gown and packing it into a box to send it up to the Hall. It was carried to the house that very morning, and Mrs Monteagle, when she took it out, was quite charmed with her new dressmaker's skill.

When the men came in from the covers that afternoon, the squire's eyes took note of the pretty gown.

"Why, Letty," said he, "where did you get that original-looking thing?"

He spoke in an undertone, standing near her little tea-table, and looking at her with an amused smile. Cardigan came up at the moment to have his cup refilled, and caught her reply.

"Alice Harper made it. A wonderful woman, isn't she?"

Had Alice Harper taken to dressmaking? Miss de Vigny had told him that she was working for herself. Later, he contrived to lead the conversation back to that tragedy which had been enacted, nearly three years ago, in Park Lane.

"I have often wondered," he said, "what became of poor Harper's daughter."

The next day was Sunday. Cardigan, who had learnt from his young hostess all that she could tell of her dressmaker, looked eagerly for Alice's face in the village church. But he could not find her there. She had gone away over the hills to a smaller church, to which the Monteagles never went, and was not to be seen with the Bowers in the seat allotted the tenants of Swallow's Nest.

He was restless, and longed to secure a little time to himself in the afternoon. Somehow, without being observed, he contrived to slip away, out of the Hall, through the gardens, and then up to that high ground from whence he had first looked down upon the old farm.

There it lay in the still sunshine, asleep in a Sunday peace. He waited there, and watched until he saw the slender, upright figure of a young woman come out of the porch. She went down the little garden-path, opened the wicket, and then sauntered slowly across the grass to the lane.

She was in a very thoughtful mood as she paced deliberately under the shade of the old oaks. The sun, now getting low, burnished the brown hair, wound so simply around her uncovered head. Once she paused to reach a spray of late honeysuckle growing on the top of the hedge, and then stood still to tuck it into the front of her dress. When she moved again and lifted her eyes, she saw Cardigan standing before her under a tree.

"Miss Harper," he said, rather awkwardly, "it is a great pleasure to see you again. You have been hidden away so long!"

"I wanted to be hidden," she answered, as she gave him her hand. "Is it not very natural that I should hide myself, Mr Cardigan? My life was darkened; it was best to live it all alone."

"I don't know if it was best," said he, reddening to the roots of his hair with the endeavour to speak his thought. "There were those who should have helped you to live it, if you would have let them."

"Ah, but I could not." Her face softly reflected the glow on his. "But, by the way," she added more lightly, "you have come to spoil the life I am leading here. I am told that you have bought Swallow's Nest, and mean to pull the old house down. Have you, by chance, given just a passing thought to those who are living under its roof?"

He flushed again.

"I confess I didn't," he said penitently. "But..."

"Oh, you rich men!" she interrupted, with a weary sigh. "With you to see is to desire, to desire is to have, to have is to leave others lacking. Shall I tell you what you were going to do?"

"Tell me anything you please," he answered eagerly.

"It is always so much easier to pull down than to build up," she went on. "The old home yonder has been years in making. More than a century ago, when it was fresh and new, a young couple began there the serious business of life. They were poor in money, but very rich in love and faith. Their prayers are built into the walls; their angels have hallowed every humble room with holy ministry; their souls passed gently from that earthly dwelling to the Father's house on high. Children and children's children have filled the places that they left vacant, living just the same simple, God-fearing life. The old house is still sound and strong; there are no cracks anywhere; it keeps out the rough weather. But a rich man has decided that it is old-fashioned and ugly, therefore it must be pulled down."

Cardigan had grown pale. Her words had gone down right to the deeps of his heart, and moved him painfully.

"It shall not be pulled down!" he cried. "Miss Harper, I have been a stupid, selfish man. But it is not too late to begin again?"

"No, it is not too late," she said, with a very bright face. "And you will really let the house stand? Well, so much the better for us and the swallows. Dear birds, they are just going away. I wonder what they would have felt if they had come back to find their old nest in ruins. Mr Cardigan, I think it is a good thing that I met you to-day. Now I must go back quickly and set some troubled hearts at rest."

"Do not go yet," he pleaded. "No one has ever given me such a straight talking to before. My money was making a selfish brute of me very fast. Hit me as hard as you can, Miss Harper. Every blow knocks some of the evil out."

She gave a soft little laugh.

"Why, it seems that I have found a new vocation," said she.

"I wish you had found it sooner!" he cried. "Can you not leave the nest to the swallows, and take me in hand? Is it too much to ask?"

There was a silence which only lasted for a moment, and yet seemed half a lifetime. The bright look faded from her face; she was perplexed and troubled.

"Mr Cardigan," she said gravely, "you must take yourself in hand."

"That means that a man should not ask a woman to do for him what he ought to do for himself," said he, in a saddened tone. "Well, you are right. I have not given any proof of amendment."

"You have given a very plain proof of a kind heart," she said, with an earnestness that made her eyes glisten. "I thank you for it. But I must go now and carry the good news indoors."

He did not try to detain her again; but, just as she was turning away, he made a last request.

"Miss Harper, will you let me see you once more before I go away? Will you meet me here again, in this spot, next Sunday afternoon?"

"I will," she said quietly. And there was a very sweet look on her face as she made the promise.

Robert Cardigan went back across the fields with a great hunger in his heart.

Robert Cardigan went back across the fields with a great hunger in his heart.

He knew now that he loved her. He had begun to love her unconsciously when she was a girl in Park Lane, looking at life with serious eyes, and talking of the things that she would do some day.

How strange it was that wealth had been taken out of her hands, and put into his. Life is full of riddles like this. Strong, tender spirits are left to work hard for a pittance, suffering the heart-thrill of those who have nothing to give but prayers and love. Lazy men and women have their hands crammed with gold, and look round constantly for some new pleasure to buy for themselves. And yet there is One who is mindful of His own.

It was a very long week. Alice, busy with her work, was conscious of a dull ache when she called up a vision of Cardigan's face. The Bowers rejoiced with a great joy. They did not ask how it was that she knew Mr Cardigan, and they promised not to speak of the matter. But they wondered silently why she, who had brought them gladness, should be sad herself.Quite alone, in the stillness of another golden Sunday, Alice slowly took her way to the quiet lane. She knew that she should find him waiting there; and she knew, too, the answer that she would give him. Yet, in her innermost self, there was a deep regret that she could not give a different answer. A man must work out his own salvation, she thought. He must not put the tools into a woman's hand, and say, "Shape and fashion my life according to your will."

"So you have come. It is kind of you," he said.

Her face was a little paler than it had been last Sunday, and her lips slightly quivered.

"You have made us all so happy," she said, in a soft, hurried voice. "The Bowers are good people, and the old place feels like a home to me."

"Do you want to stay there always?" he asked with an impatient sigh.

"I have not lived there long," she said evasively. "You cannot realise what a rest it is. For two years I worked hard in London, learning my business; and I used to pine for fresh air, and the sight of fields and trees, as only working girls can. It was Miss de Vigny who found this home for me."

"She would not tell me anything about you," said he. "Do you know what I feel when I hear of all your sorrows and struggles? I feel mad to think that I have got so much money. It seems as if Providence were playing with us both. Don't look shocked. I have a bad habit of saying odd things when I am wrought upon."

She stood still. Her face was beautiful, but very pale.

"But I didn't bring you here to listen to my ravings," he went on. "I want to ask if you can give me any hope? Will there ever be a time when we shall work together? Only tell me this!"

She turned her face away that he might not see the tears gathering in her eyes.

"How can I answer?" asked she, sadly. "I do not know. We have seen so little of each other. You are under the spell of strong feeling; but feeling only changes a man for a little while. It alters the surface of his nature, but leaves the inmost self untouched."

"Ah," he said bitterly, "you could not say that if you, too, were under the spell!"

"That is the truth." She looked up at him with a face that seemed to apologise for her words; it was so tender, as well as so true. "I am free from the spell. Because I am free, I would leave you so also. You think, just now, that you could do all the things and make all the sacrifices which I feel right. But, if we were together always, that mood of yours might not last."

"Does not love last?" he asked impatiently.

She shook her head, with a sad little smile.

"Miss Harper," he cried, "where did you learn this bitter wisdom? Why has God given us these feelings which you seem to mistrust?"

"I mistrust them only till I see what they will lead to," she said gently. "They are the beginnings of love, but not love itself. That which you call love is not lasting; it is a blossom that the wind blows away."

There was a silence so deep that they could hear the rustle of a falling leaf. Cardigan broke the pause with a voice full of pain.

"Once more," he said, "I ask if you will give me a hope? To-morrow I am going away. May I come back again?"

"Yes," she answered, with a sudden bright look. "Come back when the swallows build. They owe it to your kindness that they will find the old place just the same. Mr Cardigan, I am not as hard-hearted as you suppose. But a man must put himself to the test."

The fall of the year brought a quantity of work to the industrious fingers at the farm. Miss Harper's fame was spreading far and wide. Letty Monteagle's tea-gown was the forerunner of a great many orders from her and her friends. The squire's young wife would have been more sociable if Alice had not persisted in keeping her at a distance. More than once, when Letty tried to begin a conversation she felt herself very gently, but very firmly, checked. She had never found out that Cardigan had seen Alice before he went away.

All through the short, sharp winter, and into the early spring, the busy fingers toiled on. There was a pause when Alice paid a flying visit to a famous drapery house in London. She went for patterns and goods, but found time to see Mary de Vigny.

"Have you heard that Robert Cardigan is making himself useful?" the little lady asked. "Really useful, I mean. He came to me for advice, and I gave him some. It does not do to plunge into amateur philanthropy unaided, you see. Well, my dear, the country seems to agree with you. I never saw you looking so well, and yet you are as grave as a nun."

"Oh, that is the result of constant work," Alice replied.

In June a son and heir was born at the Hall. And then Miss Harper broke through her usual reserve, and sent an exquisite cover for the baby's cradle. The young mother wrote a cordial note, so full of genuine feeling and happiness that Alice was gladdened herself, and went out into the porch to watch the swallows. They darted round and round the old house, and the sunlight shone upon the rapid wings.

"They are building," Milly said, a little later, when the sun was pouring down upon the fields. "See, they are making their nest in the old spot!"

On the evening of the same day the farmer came indoors with a grave face. There had been an accident, he said. The squire's new groom had gone to the station with the dog-cart to meet a gentleman. It was a mistake to trust a young fellow with that flighty chestnut; in Bower's opinion the groom was as bad a whip as he had ever seen. On the way back the mare had bolted; both the men were flung out, but it was the gentleman who was hurt - very badly hurt, it was feared. They had got him to bed at the Hall, and the doctor would stay with him far into the night.

A woman, pale and sorrowful, knelt alone in her room, with her face uplifted to the stars. "If it had not been for me, he would not have come back! Oh, God, spare his life," she prayed. "Spare him, and let the way be made clear for my feet!"

Days came and went - brilliant days, full of summer sweetness and bloom, but Cardigan lay crushed and helpless at the squire's house. He was a lonely man. There was neither mother nor sister to share the nurse's watch in the sick room; but when the news of the disaster came to Mary de Vigny's ears, she wrote to the Monteagles and said that she was coming. She arrived, quiet and self-possessed as ever; and with her presence came a gleam of hope and light. The patient began to rally. Very slowly, very feebly, he seemed to feel his way back into life.

One evening Mary de Vigny sent a note to Swallow's Nest. The squire himself was the bearer. He drove to the gate in his wife's pony-cart, and waited till Miss Harper was ready to go up to the Hall.

Cardigan, propped up on his pillows, motionless and pale, brightened wonderfully when she entered the room.

"Ah, I knew you would come," he said. "I could not lie here any longer without seeing you, and hearing your voice. Do you believe in me yet, Alice? Is there any more hope for me now than there was last year?"

"Hush," she said gently. "You are not well enough to talk about these things."

"I shall never get well till I have talked about them! Alice, I want to tell you that I made my will after I saw you last. I left you Swallow's Nest, and everything else besides. Perhaps I had better die, for you will know what to do with the money. A man's life, after all, is a little thing, and I never was good enough for you. If I die..."

"Hush," she said again. "If you die, I will never marry anyone else as long as I live. But you mustn't die."

She burst into tears; and then his hand stole along the coverlet until it found hers, and held it fast.

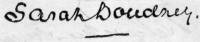

I would like to know more about Sarah Doudney

Click here to see a list of her works

If you would like me to e-mail you more short stories and/or poems by Sarah Doudney please contact me: