That Man and I, Cassell's Saturday Journal, Volume IX, December 6, 1890

Chapter I - MOTHER LIKE

ost of us, at one time or another, have had to face some crisis or emergency that may have forced our innermost self into a prominence which no ordinary combination of circumstance would perhaps have evolved. Such an extremity came into my life once, and in this wise.

ost of us, at one time or another, have had to face some crisis or emergency that may have forced our innermost self into a prominence which no ordinary combination of circumstance would perhaps have evolved. Such an extremity came into my life once, and in this wise.

I was sitting at one of the widely opened downstair windows of our lonely little house, in bondage to the influence of an ideal April evening, for beyond getting my little child, who lay asleep on the hearthrug of an inner room, into her cot, there was no duty domestic to claim me just then. My nerves were sounder at that time than they now are, and the circumstance that I was alone in the house - saving the presence, that is, of my little daughter - did not trouble me one whit, for what with my handsome and devoted husband - I was a three years' wife - my wonder of a child, and the healthy state of my affairs domestic, my mind had scant room for thief or burglar.

An accident, however, was accountable for this lonely evening, and it chanced thus. My young servant had a soldier brother, whose regiment had suddenly been ordered abroad, and that being so, Mary had entreated leave to go to London to have a last word with him. I willingly consented, and she went. Then I received a telegram in the course of the morning, giving me notice that I was not to expect my husband to return until late at night.

By the afternoon post I had a letter in which he told me where he was going - it was a business errand on behalf of the firm of merchants whose manager he was - and that he hoped to return by the midnight train. Even then the fact that upstairs in our bedroom there was a leather bag containing eight hundred pounds of the firm's money never crossed my mind. Having had to rush for his train on leaving the City the night previous, my husband - the most exact of men, as a rule - had brought home the money instead of banking it; then with the first post of the next morning - the morning of the day which was to be a marked date in our household calendar - we had news of his father's sudden death, and in the shock of the moment he had quite forgotten to take the money with him.

By the afternoon post I had a letter in which he told me where he was going - it was a business errand on behalf of the firm of merchants whose manager he was - and that he hoped to return by the midnight train. Even then the fact that upstairs in our bedroom there was a leather bag containing eight hundred pounds of the firm's money never crossed my mind. Having had to rush for his train on leaving the City the night previous, my husband - the most exact of men, as a rule - had brought home the money instead of banking it; then with the first post of the next morning - the morning of the day which was to be a marked date in our household calendar - we had news of his father's sudden death, and in the shock of the moment he had quite forgotten to take the money with him.

Seven chimed from the clock on the mantel presently; a crimson splash here and there only remained of the day's sweet glories; and after a while the moon came out, floating like a silver ball on a sleek blue sea. Our house was the only one occupied of a terrace of twenty miniature villas in an entirely new neighbourhood south of the metropolis, and my little world was so hushed then that the breath of the sleeping child was the only sound that crossed it. I was sorry that she should so sleep, for her bedtime was long past, and I was afraid she would be wakeful in the night.

It was at that moment, when I leaned forward to look into the inner room, to which my eyes were drawn as the needle is drawn to the pole, that I thought I heard a slight noise, as of a door handle that had slipped, or a foot that had stumbled. I listened, but nothing chanced, and as our cat stalked into the room at this moment, I put the noise to her account. Half-past seven! Should I light the lamp and get cosy for the evening, I wondered? Then I leaned forward, for the winds were lifting, and my nostril had caught the breath of the wallflowers under the window. It was while my senses were choke full of the sweet things that I again thought I heard a strange sound - and nearer this time - so that I decided I would go and see about it. Before I could do so much as even straighten my body, a hand - a fierce and heavy hand - was laid upon my mouth, choking the outcry backwards. I was dragged to the ground and there gagged by a man who wore a black velvet mask and a long cloak.

"My little child!" I cried within myself. "Oh, Heaven!"

"Where's the money?" said this man in accents which struck me as familiar ones even at that supreme moment. "You see I know all about it, so don't pretend surprise. Where is it? Sharp's the word, too, mind. Well?"

When I shook my head, for I could do only that, he said. "Where is it? Quick! Make a sign!" and as he moved impatiently I saw the gleam of a knife. I quailed before that, but the money - oh, no, no, no! My husband's honour was at stake there, and my own too.

"Where is it?" he said again, and though his speech was disguised as was his shape, my senses were conscious through all of that strange familiarity with his presence. "I know it's in the house, I tell you - eight hundred pounds. I've come here to get it, and I'll go when I've got it, and not before. You needn't look round; there's nobody within a mile of us, nor likely to be. Where is it? I don't want to do any mischief, but I'd cut your throat as lief as look as you if you're obstreperous. Where is it?"

I again shook my head, and I know that consideration for myself would never have moved me to act as I did had not a deeper emotion made a coward of me. He then clutched at my shoulder, and shook me with violence. His movement forward brought him in a line with the sleeping child, alas!

"Aha!" he said with a smothered yell of exultation, as he pushed open the folding doors and stood over my darling.

"One child more or less in the world won't make much difference any way, and I'm a desperate man. Oh, you needn't roll your eyes - and fine ones they are, too! Where's the money stowed? Now, look here, I'll count twelve, and that's the only chance I'll give you, you may lay your life."

It was then I turned traitor; for what with the shock of his presence, the blood-shot, wolfish eyes gleaming through the mask holes, and that ominous glitter that came from the inside of his cloak, I felt my brain reel. At that moment I was the mother, whose child was in danger, only. I writhed in my agonies, but my bonds were hard ones, and he said "nine" with a cruel downward glance at the little sleeper, over whom he loomed like ogre upon dreaming fairy. I do not know whether I was or was not a responsible being at that moment, but when he got so far as "eleven" and stooped towards my darling, I made a gesture of submission, and he understood.

"Where?" said he, feverishly; and I glanced above me. "Upstairs? Room overhead? Good. If I don't find it sharp, I'll come back for particulars."

In less than ten minutes he returned, and in his hand he carried a leather bag, upon which I looked with burning, hungry eyes, for it had in it the master's gold and the servant's honour. Ah, my heart was full then! It overflowed.

He put the money safely out of the way, and then brought forth a roll of strong cord. With that he made more secure the fastenings which held me, assured himself that I was soundly gagged, and finally produced a small phial from his waistcoat pocket. My brain was like to rend when I saw that, and something of my horror must have expressed itself, for he said, with a dry chuckle -

"Only a soothing syrup for the young 'un. No; there's no harm in it. I've got what I wanted, and that'll do for me. I must see to my retreat, you know, and it wont do to have any squalling for the next hour. Keep still; keep still now. It's only a syrup, I tell you, to prevent any accident."

And I had to lie there, bound hand and foot, and see him put the contents of the phial down the child's throat. She whimpered a bit, and spluttered too, but relapsed, after a few spasmodic smiles, into unconsciousness. He came back to me then with a grunt of satisfaction.

"No harm done," said he. "Sorry I have had to treat you rather roughly, but couldn't help it, you see. You'll be all right presently. Good-night!"

With that he crept stealthily out of the back ways, and once freed of the incubus of his presence, my stunned senses began to thrill. He had left the folding doors open so that I could see my little daughter, and it was then my real agonies - the mother's - began. Why was she so still? What had he made her drink? Did she breathe? Supposing, supposing - Oh, Heaven! could such horror be? I stopped my breathing to listen for hers. I heard none. Why did she never once move or murmur? Supposing - no, no, no! Heaven would surely have mercy on me.

And the night approached. I could scarcely see her at last, and neither sound nor movement came from the beloved form. Gradually, born of the darkness and terror of my situation, came the idea that she was dead, or dying from want of help; and before that idea, being her mother, I went clean mad. Body and soul seemed at that moment to heave asunder; my brain rocked; I lost my foothold of the earth; it opened greedily, and I went headlong into its fathomless horrors!

Chapter II - FACE TO FACE

I knew myself no more after that, save a blank creature whom the animal's instincts guided in all things. I remember how I used to walk hand-in-hand with a little child, whose touch I loved, and towards whose voice my ears leaned. At times I thought I was a child as she was, and when that was so I used to sit with her on the floor: used to sing to the dolls, dress and fondle them, and run behind the doors to hide from her when we played. Sometimes I had a cruel pain in the shape of a recollection of a little child whom I thought I had lost in a storm when I was out on the hills one day. Those were the days when I wept for hours together, because I thought I was still out in that storm, toiling up the steep hill on which I had lost that little child. I can remember how she used to wipe my eyes when I cried so, and say soft words to me if I asked her whether she had seen my little child. Sometimes, in the midst of my grief, she would lay the doll into my arms, and I remember how I would laugh then and kiss it, content and forgetful once more. The figure of a man and that of a woman, who had a face like his, and wore a big frilled hat, I also remember distinctly. How pale and silent they were.

I knew myself no more after that, save a blank creature whom the animal's instincts guided in all things. I remember how I used to walk hand-in-hand with a little child, whose touch I loved, and towards whose voice my ears leaned. At times I thought I was a child as she was, and when that was so I used to sit with her on the floor: used to sing to the dolls, dress and fondle them, and run behind the doors to hide from her when we played. Sometimes I had a cruel pain in the shape of a recollection of a little child whom I thought I had lost in a storm when I was out on the hills one day. Those were the days when I wept for hours together, because I thought I was still out in that storm, toiling up the steep hill on which I had lost that little child. I can remember how she used to wipe my eyes when I cried so, and say soft words to me if I asked her whether she had seen my little child. Sometimes, in the midst of my grief, she would lay the doll into my arms, and I remember how I would laugh then and kiss it, content and forgetful once more. The figure of a man and that of a woman, who had a face like his, and wore a big frilled hat, I also remember distinctly. How pale and silent they were.

How they used to sit and look at me, and cry sometimes when I was most happy with that little child and the dolls. On the days when I thought I was out in the storm I used to hang upon their arms, asking them the livelong day, "Where is my little child? Tell me, tell me! Have you seen my little child?" I have a remembrance, too, of how they used to put on my garments, tie strings, kiss me, feed me as I sat with the little creature I loved; how they led me tenderly by the hand as we walked in a garden together! One day, when I had striven for hours, it seemed to me, with this merciless hill, I crept into the garden, for I was hot and tired, and I loved to watch the clouds and the flowers. No one held my hand then, and I wondered vaguely how that was, as I leaned against the walls of the house.

The next thing I remember is a sudden loud noise and a heavy shadow, and that my heart beat fiercely, for a man had leaped from the wall opposite to me and dropped into the garden at my feet. When I saw that man, the shadows slipped from my brain as snows slip from the hills before the sunbeams; and as he looked at me he threw up his arms and cried aloud -

"Helena! Helena! Oh, what a bitter sight!"

But I was running into the house then, weeping, laughing in a breath, for I had not lost her, after all. Lost her, indeed, when I had her in my arms and was kissing the breath from her scared little body. It was a fierce clutch of my gown that made me remember that evil presence, and the tiger that wakes in the female, whose young is hurt, awoke in me then.

"The police are after me!" he gasped. "Save me!"

But I could only think of him as the blood-thirsty wretch who would have butchered a sleeping child.

"If I could hold you fast, I would," I answered: ay, and I know I showed my teeth. "Where is the money, Philip Barnes?" I asked; for I knew him now as the thrice-rejected lover of my girlhood, prodigal son, and gambler.

"Gone, every penny; but I'll make what reparation I can - I swear I will; only help me, Helena. Don't turn from me in my extremity. Oh, mercy! am I to die by the rope after all?"

"What have you done?" I asked, wrenching my gown from his clutch.

"Stabbed a sharper."

"Dead?" I whispered, aghast.

"I hope so," said he, with a savage smile. "Help me, Helena. Before Heaven I will confess."

I had my little child in my arms; my husband's honour - ah, I knew that pale and silent man now who had hovered about me - would be vindicated; I looked at the hunted, cowering wretch, and my injuries burned less fiercely.

"Heaven help you," said I; "I will not betray you. Go your way." I was only a woman, after all.

"Some clothes!" he gasped. "Hark! what is that? Women's clothes. Quick, Helena!"

"Clothes?" I said in bewilderment. "What for?"

"Yes, yes, yes, for disguise. I must stop here and face them. Tell me where I can find them. Quick, quick."

I ran into the bedroom, in which the old lady, whom I now recognised as my husband's mother, kept her clothes, and handed out to him the necessary garments. In the space of a few breathless seconds this wretched creature was seated at the kitchen window as placid an old woman as you might wish to know. He had no beard, fortunately for himself, and the big, black-framed spectacles and the clumsy woollen stocking he had drawn over his hand completed the disguise. He was no sooner settled in the wooden armchair than a posse of breathless police folk invaded the back premises. Their leader civilly explained the urgency of the case, after which they fairly ransacked the house. No one, however, seemed to question the genuineness of the substantial old woman, who looked with stolid reproach over her spectacles as they poked about. I do not suppose that more than a quarter of an hour had passed since the moment of Barnes' appearance when I shut the street door upon the intruders.

We waited in feverish silence a few seconds lest they should return, or others come, but no further disturbance occurred; and drawing my little Nellie into my lap, I sank into a chair, wholly exhausted.

Chapter III - THE RECOIL

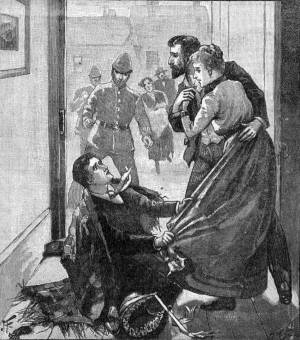

He flung off the disguising garments and fell at my feet.

He flung off the disguising garments and fell at my feet.

"Forgive me!" said he, with heaving breast. "Having helped me, forgive me."

But I could not do that; 'twixt him and me loomed that evil thing that had threatened my little child.

"Go," said I, "or stay, if you are safer here, but do not ask me to forgive you, for I cannot."

"Forgive me!" he cried, and the tears ran like rain; "I can never sleep again unless you do. Give me the mercy that I refused to you, Helena; it may help me to a better life."

But my heart had no mercy in it - it was as of stone. I asked him indeed how he could expect of a mother, whose child he would have destroyed, that she should forgive him, and he sprang to his feet; then, with a look of horror -

"No, no," he cried, in passionate denial; "I never meant to harm the mite; I only did it to frighten you."

"Is that the truth, Philip Barnes?" said I, and I bent towards him.

"Yes, I swear it is!" answered he; and I put out my hand to him, and said that I forgave him as I hoped that in my need I might be forgiven. I reminded him that he must make speedy reparation to my husband; that he should not have taken off the woman's clothes; and said that I hoped to have prompt news of his safety.

His lips opened then as if he would have spoken, but no words came. He sat down at the table, hid his face on it, and shuddered violently. Poor hunted, debased, desperate creature! my soul ached for him now. I said nothing of my grievous affliction - I believe I so refrained because I wished to spare him further suffering; the disguising clothes I urgently advised him to put on again, and to wear them till he should be in a place of safety. He thought earnestly for a second or two, and then said he would do so.

"Is this your address, Mrs Debenham?" he asked, referring to an envelope that lay on the table, and the words shocked me to the soul, for I realised that I could not have told him had he asked me where we lived even, and the sound of my name thrilled me. I nodded quietly, however, and he put the envelope into his pocket.

"I will send back the clothes in a day or two," said he, "and write to Hubert's employers directly after I am in safe quarters."

Then I got out bonnet, shawl, umbrella, and market basket for him, and helped him generally. The greatest difficulty the boots made, for nothing was available that would have done for him. A few moments after we entered the passage, and I opened the street door and looked out. I saw nothing to make me suspicious. It was a poor kind of place, where empty houses and dinginess prevailed, but I thought he might start. He was ghastly pale as he came forward, to his lips even; he put an ice-cold hand into mine, and whispered some hoarse and broken words.

I answered him, and said "good-bye" with what composure I could and he went slowly and without a backward glance down the street. As soon as he had turned the corner, I shut the door and went in, and realised there and then, the wonder and ecstasies of the two people for whom I now waited. And fast to my brain, as the limpet to the rock, clave the words I had seen on that scrap of paper: "Mrs Debenham, 17, Rexley Street, Walworth." Oh, what music I got from them, to be sure, as I said them again and again! Suddenly I heard the click of the garden gate. I flew through the narrow passage. A woman was speaking; a man's voice answered her; and I knew them both.

"Well, you know what a tramcar accident means," said she. "Why, I didn't think I should be gone more than twenty minutes. Don't worry, Hubert, dear; she'll be all right. What is the matter with the lock?"

"That's what I want to know," he answered. "Don't go out again, mother, unless I am at home; it's such a risk."

The door opened then, and forgetful of all save my own transports, I threw myself on my husband's breast. He staggered into the passage, and there leaned gasping against the wall. And his face! the giant wonder and joy of its eyes! the glory!

"You know me!" he whispered, hoarsely. "It is too much, too sudden;" and he reeled like a drunken man.

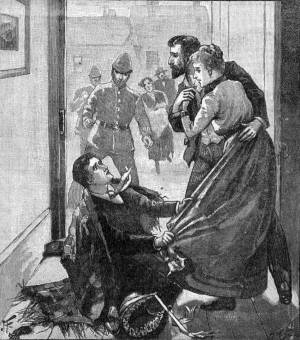

How they kissed and fondled me, half carrying me into the kitchen - oh, I can never again forget it! I poured out my story then, and they listened with dilating eyes. At the moment when I was about to ask how long I had been irrational, I heard a strange, heavy sound as of a body falling, and then a choked, but bitter cry. I ran forward and opened the street door. A ghastly creature, with death on its face, fell prone upon me as I did so, and bore me with it to the ground. My husband put me on my feet with a cry of dismay, and the wounded man clutched wildly at my gown then.

"Let me die here," he cried; "I'm done! I'm done! Don't have me dragged out again. Oh, my mother!"

Policemen and excited people ran up here. In the foremost of the officers I recognised the leader of the search party.

"I didn't quite believe in the old lady, ma'am, so we laid by a bit," said he. "You see, he had the stocking on the wrong hand, and no wedding ring. And when I was going out I caught sight of one of his boots. He's done for, ma'am. We had a bit of a tussle, and his pistol went off. Do you mind having him here till we get a cab to take him to the hospital? Not that it's any use; he's shot through the lungs I think. Lay hold, Harry: that's it. Off you go to the nearest cabstand."

"No, no, no! My time is come; let me be," moaned the wounded man. "A magistrate, quick! Helena, you know. Oh, Heaven! A drink of water; I'm going fast."

Magistrate, doctor, the head of the firm, and Hubert Debenham were gathered in due time about the dying man.

To them, in gasps and almost incoherent at times, he made confession of the wrong he had done to my husband and to others besides him. He had always hated him, it appeared, but his rancour culminated when he succeeded as a lover where he had been three times rejected. He was head clerk to the merchants whose manager my husband was, and to him, for he is the most unsuspecting of men, Hubert mentioned the fact that he had omitted to deposit the money. I discovered then for the first time that this unscrupulous man had been undermining his rival's business position for months past, and so secretly that Hubert, my husband, who was conscious of having an enemy, never suspected him in the least of being that enemy. The loss of the money, in circumstances so extraordinary, was as the last straw to the camel's back. The principals did not prosecute, but their attitude was such that my husband resigned of his own accord, which, it appeared, was exactly what they wished he would do.

Our enemy, I heard later on, had left the firm very shortly after my husband's disgrace, but no suspicion ever touched him. When our servant returned on the night of the tragic occurrence, she raised a hue and cry that brought the policeman on duty to the house; but except the disappearance of the money and the terrible condition in which I was found, no evidence of a bonâ-fide burglar's entrance was forthcoming.

When I recovered from the violent illness which ensued, I was that vague creature which I remember myself to have been, and such I continued to be throughout the year which had passed. Mary was gone, and my husband's mother had taken my place as far as was possible. We had lived, they said, as best we could meanwhile, in a locality as poor as were our circumstances.

The details of Philip Barnes' conspiracy we never knew - his time and understanding gave out - but his dying statement fully exonerated my husband, and Mr Moore, his principal, put out his hand and begged him to resume his former duties on the morrow, and along with them offered heartfelt regrets and apologies and an increase of salary.

It was late in the evening when peace once more descended upon our poor little house. The strangers were gone, and our enemy lay under our roof - dead!

Five years have passed since, but I remember keenly that moment when I went with my husband to the death chamber, and saw the convulsed and ghastly face take gradual shape in the obscurities. I folded the rigid hands, and put the flowers I had brought into them, and, woman like, I cried as I did so, for if he had sinned, he had also suffered, and his malignities had brought their own recoilment.

HOME

Read more anonymous stories: Rosaline Ellerton; or the Fruits of Indolence, "I Promised Father", My Wicked Ancestress, Lady Charmeigh's Diamonds, Mistress Molly's Moonstone, Stapleford Grange, The Change of Heads, A Lodging for the Night.

ost of us, at one time or another, have had to face some crisis or emergency that may have forced our innermost self into a prominence which no ordinary combination of circumstance would perhaps have evolved. Such an extremity came into my life once, and in this wise.

ost of us, at one time or another, have had to face some crisis or emergency that may have forced our innermost self into a prominence which no ordinary combination of circumstance would perhaps have evolved. Such an extremity came into my life once, and in this wise. By the afternoon post I had a letter in which he told me where he was going - it was a business errand on behalf of the firm of merchants whose manager he was - and that he hoped to return by the midnight train. Even then the fact that upstairs in our bedroom there was a leather bag containing eight hundred pounds of the firm's money never crossed my mind. Having had to rush for his train on leaving the City the night previous, my husband - the most exact of men, as a rule - had brought home the money instead of banking it; then with the first post of the next morning - the morning of the day which was to be a marked date in our household calendar - we had news of his father's sudden death, and in the shock of the moment he had quite forgotten to take the money with him.

By the afternoon post I had a letter in which he told me where he was going - it was a business errand on behalf of the firm of merchants whose manager he was - and that he hoped to return by the midnight train. Even then the fact that upstairs in our bedroom there was a leather bag containing eight hundred pounds of the firm's money never crossed my mind. Having had to rush for his train on leaving the City the night previous, my husband - the most exact of men, as a rule - had brought home the money instead of banking it; then with the first post of the next morning - the morning of the day which was to be a marked date in our household calendar - we had news of his father's sudden death, and in the shock of the moment he had quite forgotten to take the money with him. I knew myself no more after that, save a blank creature whom the animal's instincts guided in all things. I remember how I used to walk hand-in-hand with a little child, whose touch I loved, and towards whose voice my ears leaned. At times I thought I was a child as she was, and when that was so I used to sit with her on the floor: used to sing to the dolls, dress and fondle them, and run behind the doors to hide from her when we played. Sometimes I had a cruel pain in the shape of a recollection of a little child whom I thought I had lost in a storm when I was out on the hills one day. Those were the days when I wept for hours together, because I thought I was still out in that storm, toiling up the steep hill on which I had lost that little child. I can remember how she used to wipe my eyes when I cried so, and say soft words to me if I asked her whether she had seen my little child. Sometimes, in the midst of my grief, she would lay the doll into my arms, and I remember how I would laugh then and kiss it, content and forgetful once more. The figure of a man and that of a woman, who had a face like his, and wore a big frilled hat, I also remember distinctly. How pale and silent they were.

I knew myself no more after that, save a blank creature whom the animal's instincts guided in all things. I remember how I used to walk hand-in-hand with a little child, whose touch I loved, and towards whose voice my ears leaned. At times I thought I was a child as she was, and when that was so I used to sit with her on the floor: used to sing to the dolls, dress and fondle them, and run behind the doors to hide from her when we played. Sometimes I had a cruel pain in the shape of a recollection of a little child whom I thought I had lost in a storm when I was out on the hills one day. Those were the days when I wept for hours together, because I thought I was still out in that storm, toiling up the steep hill on which I had lost that little child. I can remember how she used to wipe my eyes when I cried so, and say soft words to me if I asked her whether she had seen my little child. Sometimes, in the midst of my grief, she would lay the doll into my arms, and I remember how I would laugh then and kiss it, content and forgetful once more. The figure of a man and that of a woman, who had a face like his, and wore a big frilled hat, I also remember distinctly. How pale and silent they were. He flung off the disguising garments and fell at my feet.

He flung off the disguising garments and fell at my feet.