As a young Cuban exile in Miami and, later, as an actor doing hard time in Hollywood, the star of The Godfather, Part III learned how to take the heat in style.

From "GQ" magazine, December 1990

By Stephanie Mansfield

Steams seems to be rising from the Key Biscayne sand as the late-August sun blasts down, the oppressive wall of tropical heat broken occasionally by small puffs of ocean breeze coming off the aqua-blue bathtub of the Atlantic. Andy Garcia is on his second rum punch, rattling the melting ice cubes in the plastic cup. His face is a road map of Havana: sleepy, burnt-sienna eyes; long, straight nose; and the sensual, slightly overripe lips of a matador or some other charismatic killer. He hasn't shaved for a day or so, and the midnight stubble mixed with a faint dew of perspiration gives him a rakish machismo, as does the green paisley bandanna pushing his long, thick, straight brown hair off his forehead to reveal the dark arrow of a widow's peak.

For two hours, he has done a verbal mambo: about emigrating from Cuba at the age of 5; about Castro and what the revolution did to the García family; about Zoom Zoom Zami and the girls from Manhattan down on spring break; about growing up as a streetwise kid when you could sneak into the back of Johnny's at 2 A.M. to soak up the bongo beat of Mongo Santamaria and still find a patch of Miami Beach without a Hilton jammed on it. He is articulate. Amiable. With a smooth, rhythmic charm. A percussionist by nature. Then the talk turns to his early years in Hollywood. The lyrical voice that caresses the language, deadens. The palm fronds are flick-flicking overhead, the rum is kicking in, and Garcia turns steely.

"I was rejected. And in the rudest of ways. I was seven years in Hollywood before I got The Mean Season. I have a lot of horror stories; some of them we won't go into. All the racist kinds of things. There was one agent who I went to see when I first got to Hollywood who said, 'Fix your teeth, change your hair, and lose your accent and I'll represent you.' When you're a 21-year-old kid, what do you think? You're coming into a foreign world. You're stepping in very naively, no matter how tough you think you are.

"After I'd been there almost a year, I got an interview for a part. I walked in the door and the woman said, 'Yes? What are you doing here? What's your name?' 'Andy Garcia,' I said. She looked up and said, 'You're not Mexican.' She finally found my photograph. 'Huh,' she said. 'We're looking for Mexicans.' I said, 'I'm an actor. I can play Mexican.'"

He smacks the plastic cup against his lips and crunches a mouthful of ice. He wears a thin gold wedding band on his left hand, an L.L. Bean canvas-strap watch, a T-shirt, loose cotton pants and woven-leather espadrilles. At 34, he is not as thin as he'd like to be, hovering at 173 pounds, a good ten pounds over his fighting weight.

"I remember one time I went to read for a television pilot," he says, lowering his gaze. "I waiting and waited for forty-five minutes. Finally, she comes in."

After taking a phone call, the woman hung up and asked Garcia to read the dialogue.

"Are you in shape?" she asked.

"What do you mean?"

"This part requires you to be in very good shape. Take your shirt off."

Garcia declined.

He lost the job.

A small smile crosses his lips. He doesn't think the woman, the head of casting for a major television studio, is still in the business. "All I know is," he says, leaning forward, "I'm still here and she ain't."

He says this without bitterness or, por favor, disrespect. The point is, such people were in positions of power. They were holding the letters of transit. They were getting in the way, man. And they were not, as Garcia heatedly says, "entitled."

But Garcia was patient. He kept his head down and his mouth shut and his shirt on. He learned the process. He made connections. Like his father twenty years before him, he was a stranger in a strange land. And if his family back in Miami privately worried about when and if this "acting thing" would ever pay off, Garcia - born with what Cuban author G. Caberera Infante describes as "what gauchos, cowboys and Mexican rancheros are made of: stud stuff" - never looked back. He had big dreams.

So does Paramount Studios, which began to cultivate Garcia in 1987, after his scene-stealing turn in Brian DePalma's The Untouchables. Garcia originally went up for the role of gangster Frank Nitti but got the part of good guy Italian cop George Stone instead. It was a major stroke of luck, and Garcia capitalized on his relationship with the powerful studio. This year's police thriller Internal Affairs, costarring Richard Gere, was written with Garcia in mind, but before that script was finished, the part of Michael Douglas's sidekick in Black Rain, another cop, came along. In the summer of 1989, when Francis Ford Coppola finally told the studio he would direct a third Godfather film, Andy Garcia's name hovered at the top of the list of actors to play Vincent Mancini, even though Coppola wasn't familiar with Garcia's work. Overcoming the initial stigma of being the studio's boy, Garcia blew Coppola away with his screen test and copped the role of Mancini, the hotheaded, illegitimate son of the deceased hothead Sonny Corleone.

So does Paramount Studios, which began to cultivate Garcia in 1987, after his scene-stealing turn in Brian DePalma's The Untouchables. Garcia originally went up for the role of gangster Frank Nitti but got the part of good guy Italian cop George Stone instead. It was a major stroke of luck, and Garcia capitalized on his relationship with the powerful studio. This year's police thriller Internal Affairs, costarring Richard Gere, was written with Garcia in mind, but before that script was finished, the part of Michael Douglas's sidekick in Black Rain, another cop, came along. In the summer of 1989, when Francis Ford Coppola finally told the studio he would direct a third Godfather film, Andy Garcia's name hovered at the top of the list of actors to play Vincent Mancini, even though Coppola wasn't familiar with Garcia's work. Overcoming the initial stigma of being the studio's boy, Garcia blew Coppola away with his screen test and copped the role of Mancini, the hotheaded, illegitimate son of the deceased hothead Sonny Corleone.

While Paramount was grooming Garcia, the actor had his own agenda. At every opportunity, he used his growing clout to bring other Hispanic actors and projects to the studio's attention. The smooth-talking front man for a rag-tag Cuban mafia, Garcia has managed to get numerous jobs for friends and is now developing his own Cuban project for Paramount. The 61-year-old exiled Infante will write the script, and Garcia will produce the film and star in it.

Not bad for a gap-toothed homeboy (old photos show a space between his front teeth) who used to pick up empty pop bottles from the streets of Little Havana for extra nickels and sweep out the sock warehouse where his father worked.

"How long is this interview gonna last?" Garcia asks good-naturedly as the waitress sets down our drinks. "'Cause I don't want to get too drunk. I might say something. Do you think I should trust this lady?" He stops laughing. "Why am I telling you all my precious stories."

Probably because it's so god-awful hot. And there's something seductive about this local hangout of a beach bar and the way the light dapples the palm branches and the fact that Cuba is only ninety miles away. Instinctively, people tend to peel off. Garcia takes off the bandanna and kicks back, not ready to leave.

He flew in from Los Angeles the night before and will stay in Key Biscayne for a few weeks, visiting his family and scouting locations for the Cuban project before additional shooting for The Godfather, Part III begins in New York.

When he was a kid, Garcia used to tag along with the older crowd and stay out all night. "We'd drink coffee at the Royal Castle, on 71st Street. We were street urchins in a way. The ocean was right there. On Collins Avenue. We'd wait for the American girls to come down to Miami Beach and try to pick them up. These girls came with a purpose." His brown eyes are dancing. "They were here to have a good time. We were trying to cater to their needs, that's all. There was a guy called Zoom Zoom Zami. He was the guy you oughtta stay close to. I'd just watch Zoom Zoom work." Garcia idolized Zoom Zoom, who was everything Garcia was not: a free spirit, disconnected from home and hearth.

Garcia was not actually a street urchin. He came from a tight-knit, hardworking, conservative Catholic family. He smiles and rolls his eyes. What kind of girl would go for that? They were looking for adventure. Exotic, hot-blooded Cuban boys with skintight pants and forbidden, dark-eyed lust. "I presented myself as the wrong kind of guy," Garcia says now. "I was acting. Even at that age."

They used to be called Vaselinos, the slick Latinos who came to Hollywood with dreams of becoming the next Valentino. Ramon Novarro comes to mind. So does Cesar Romero. As the years went by, it was easier and easier to typecast such ethic actors. Andy Garcia goes against that grain. He has escaped this cultural stereotype through the sheer magnitude of his talent, and although his house is currently blanketed with wall-to-wall scripts calling for jealous, macho cops, Garcia has tired of such roles.

They used to be called Vaselinos, the slick Latinos who came to Hollywood with dreams of becoming the next Valentino. Ramon Novarro comes to mind. So does Cesar Romero. As the years went by, it was easier and easier to typecast such ethic actors. Andy Garcia goes against that grain. He has escaped this cultural stereotype through the sheer magnitude of his talent, and although his house is currently blanketed with wall-to-wall scripts calling for jealous, macho cops, Garcia has tired of such roles.

Coincidentally, he's a decent guy. Un buen hombre. "There's no bullshit," says Black Rain director Ridley Scott. Faithful, loyal, compulsive, devoted. "Devoted to his family, his dogs, his work, his golf, his culture, his music," says Garcia's friend William Marquez.

Solidly wedded to Marivi, his wife of eight years, he has two daughters, Dominik, 7, and Daniela, 2 1/2 and still parks a beat-up blue Volvo in front of his modest home in the San Fernando Valley. His marriage is described as "a beautiful relationship" by close friends, who say Marivi Garcia - calm, cool and a marvelous cook - keeps her husband well-fed and grounded in reality. "If I ever heard Andy got divorced," says an old friend, "I'd know that he had changed."

Mindful that his marriage is the safety net, Garcia still indulges in occasional flirting, perhaps more of a genetic Latin American trait than a conscious effort at seduction. "What do you expect?" says one of Garcia's friends with a laugh. "We've been taught to do that since we were 2."

But for all that, Garcia is still somewhat modest. He has never done a nude scene onscreen. In fact, he has never taken his shirt off on film. (Even in bed with his onscreen wife, Nancy Travis, in Internal Affairs, Garcia makes love in his Hanes.) Still, the chaste and chiseled Garcia might be the perfect safe-sex cinematic fantasy for the Nineties: intense and unattainable, with a sensuality all the more powerful because it's from the neck up.

"I don't think Andy would do anything on film his family couldn't see or be proud of," says director Jerry Schatzberg, who worked with Garcia on the HBO movie Clinton and Nadine. At Garcia's suggestion, Schatzberg also cast William Marquez, Mario Ernesto Sánchez (director of Miami's Teatro Avante) and Andy's old friend and schoolmate Alfredo Alvarez-Calderon. "They're all extremely cordial people. Honorable. Loyal. Andy is that way." Schatzberg says. "It's very difficult not to get along with Andy."

"I don't think Andy is at all angry," says Sánchez. "He belongs to a generation of Cubans who are very happy to be here."

"I will say this about Cuban men," explains Jo-Dee Mercurio, a costume designer who has worked with Garcia and who grew up in Miami. "They will do whatever they have to do. Work hard, make it and hold on to it. It's God's gift to you. Don't fuck it up."

René Garcia was already middle-aged when his third child, Andrés Arturo García-Menendez, was born in Havana, on April 12, 1956. René's wife, Amelie, taught English, and René, a lawyer, owned extensive farmlands in the town of Bejucal. Rarely at a loss for words, René Garcia was known as the Mayor. His wife was blessed with an infectious sense of humor, and it was said that if a group of people were gathered together in a corner laughing, Amelie Garcia was always in the center.

But the Garcia's charmed life was shattered in 1959, when Fidel Castro came to power. "They started nationalizing the banks and started taking your property away from you and changed the monetary standards," Garcia says. "They would just come in and say, 'This hardware store now belongs to the revolution and you can work for us.' My father's breaking point was when they said, 'In the coming year, you turn the rights to your children over to the state' and they immediately took part in what they called 'the educational program,' which was basically an indoctrination program."

Andy Garcia was only 5 at the time of the Bay of Pigs invasion, but his older brother recalls the roar of the B-26 bombers over Columbia Military Camp, not far from their home. After the failed attempt by expatriate Cubans to overthrow Castro, Amelie Garcia handed Andy a glass of orange juice on the front steps of their house and told him that in two days they would leave on a plane for Miami. His father stayed behind in Cuba for a few months before joining his wife and children - Tessi, then 10, René Jr., 8, and Andy - in exile. They were members of the first waves of Cuban refugees, the intelligentsia and the entrepreneurs who crowded into Miami's Freedom Tower the same way the fictional Vito Corleone passed through Ellis Island.

In Miami, the Garcias' standard of living plummeted. "We grew up very fast," says Tessi Garcia, now a community activist in Miami and the president of her own interior design firm, in Coral Gables. Tessi, whose privileged childhood had included a nanny and ballet and piano lessons, took care of her younger brothers who did not speak English and who entered the assimilation process fists-first. This early upheaval instilled in the Garcia children a hunger for success. (Now the president of a thriving perfume company, René says, "We're all overachievers.")

Andy was the sensitive one, but too young to fully comprehend what the family had lost. "I wasn't really deep-rooted in anything yet," he says. The memories are hazy, but he is obsessed with trying to capture those years for his upcoming film. His voice drops, "I do regret not growing up in Havana. I'll always miss that. I can't go back, but I can re-create it."

(Garcia was recently offered a starring role in the upcoming film version of the Pulitzer winning The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love but turned it down in favor of his own project. "How many Mambo Kings can I make?" he quips.)

As a schoolboy in Miami Beach, Andy was small for his age and was hampered by his inability to speak English. "I obviously had a language barrier," he says. "That was evident early on in school. I was in a fight almost every day. My brother would have to come to the principal's office two or three times a week. I would be sitting there and someone next to me would say, 'You wanna borrow one of my crayons?' and I'd beat him up. I didn't know what the hell he said, but just in case, let me beat him up, I was, like, the bully of the school and I was the smallest kid."

He attended Biscayne Elementary School and later went to Miami Beach Senior High, alma mater of Barbara Walters and Mickey Rourke. His mother worked as a secretary, and his father had started a Cuban-food catering business, called Biarritz. "He didn't make any money at it, but we ate well." Garcia recalls.

Then René Garcia became a jobber for 11-11 Caffino Hosiery, whose products were distributed in the Caribbean islands. "My father, every single morning at seven o'clock, he's in the truck, vroom, going to work. Drop me off at school and go," Andy says. "He'd come home at eight o'clock at night, six days a week. Every day, boom, boom, like a metronome. After school I used to go to basketball practice and then take the forty-five-minute bus ride from Miami Beach to downtown Miami. I'd go to his warehouse and sweep the floors, get in the car and go home. And he expected that of me." (His father, now 74, had part of a lung removed last year and suffers from myasthenia gravis, a debilitating muscular disease.)

Like other children whose parents worked long hours, Andy was zooming with a fast crowd. "I think I was always the father figure, trying to protect him," says his brother. At first, he saw Andy as a social liability. But when they went to discos at night, his kid brother with the bedroom eyes who played the piano and the bongos would attract enough women for the entire group. "Everybody wanted to be with Andy," René recalls with affection. "He was always a magnet."

"In all the sports I played," Garcia reflects, "it seems I always was controlling a team. I played point guard. I played quarterback. I played shortstop.

"If I could have made a living as a basketball player, I would have. Acting is very much like a game of basketball. There's a moment-to-moment, spontaneous thing about it. You don't know what's going to happen. All you can do is warm up and prepare and then the game starts. Sometimes you have a great game." After a bout with mononucleosis, Garcia lost his athletic edge. At five-foot-eleven, he was too small for college basketball, and his grades were mediocre. "Harvard wasn't exactly beating down the door," one teacher recalls. The only college he could attend was the state school built on the old Tamiami Airport, Florida International University, where his brother had gone.

While at FIU, unfocused and in limbo, Garcia decided to try out for a play. No experience necessary, the audition notice said. "I knew I had to make a living," he says now. "It was time to grow up." So he took up acting.

He says it was like a virus, growing stronger and finally consuming him: "That was when my true calling came out. And it came out in such a force because I wasn't distracting myself with another activity." He was attracted to the creative process, and the life of an artist gave him a certain "solace." He says he was fortunate to find acting. "I was lucky to have a passion for something. I don't have the ability to survive like Zoom Zoom Zami does."

People thought of the long-haired Garcia as low key, and a gentleman. He seemed mature for his age. "While the other kids were goofing around, he was putting his shit together," says Mario Sánchez, who directed Garcia in a Spanish-language version of Anatasia. "They were all smoking pot, and he was figuring out the steps he needed to take to get a chance. He was very disciplined."

"I'll tell you what one teacher said," recalls Alfredo Alvarez-Calderon: " 'He listens very well. You talk to him, he is there.' "

He left school in 1977 to do a film in the Dominican Republic and never returned to graduate. He and Alvera-Calderon got acting jobs, one of which required them to appear at a Puerto Rico hotel dressed in pirate costumes. Waiting for the bandleader to arrive, they polished off a bottle of scotch, got into a drunken sword fight and were asked not only to leave the hotel but the island.

Garcia knew he had to move to Los Angeles if he really wanted to make a career of acting. He found a small apartment in Hollywood and began waiting tables and working on docks. His acting jobs included a brief run as a young gang leader on Hill Street Blues. In the meantime, he had already met Marivi. "He came to my place one day and showed me a picture of her," Marquez recalls. "He was so proud, I'll never forget that. He was, like, 'This is my girlfriend. This is it.' The next thing I knew, he had gone back to Miami to marry her."

It was in Miami in 1985 that Garcia got his first film break, a small part as a Hispanic detective in The Mean Season. During the shoot, a friend of one of the producers came to town. His name was Fred Roos. "I was a fan of Andy's way before people were aware of him," says Ross. "Andy took us all out to a Cuban restaurant. So I kind of met him socially, and I've been charting his career ever since."

It was a powerful connection. The soft-spoken Roos, long associated with Coppola, had been the casting director for The Godfather and had coproduced The Godfather, Part III.

Then came another lucky break: the late director Hal Ashby cast Garcia in 8 Million Ways to Die, as Angel Maldonado, the ponytailed coke dealer who keeps passion-fruit snow cones in his trunk and lives in a Gaudian palace. The critics instantly took notice of the young unknown. As Pauline Kael wrote in The New Yorker, "He does the Latino sleaze and volatility to hammy perfection, flashing his eyes like semaphores. . ." Ashby had instinctively known that Garcia was a strong improviser and had allowed the actor free rein. "I was spoiled by Hal Ashby tremendously," says Garia. "He was absolutely the greatest. He was truly gifted. Like a beatnik director, unconventional, daring, really trustworthy. I measure a lot of people by Hal. And a lot of people don't measure up.

After The Untouchables, he starred in American Roulette, a British-Australian television movie. In Stand and Deliver, with Edward James Olmos, he did a cameo as a state official questioning the results of high-school students' test scores. It was a favor to the film's Hispanic director, who needed a little star power.

Black Rain saw Garcia playing Michael Douglas's doomed partner. They got along well. "Every time I see him he says, 'So when are you gonna carry a movie? Come awn. Come awn. You come in, work two scenes, steal the movie!' " Garcia was killed off three quarters of the way through the film, but not before making a memorable impression with a raspy version of Ray Charles's "What'd I Say?" in a Japanese nightclub.

In the summer of 1989, Garcia was wrapping Internal Affairs when Paramount chairman Frank Mancuso asked him what he was doing in November. The Godfather, Part III was scheduled to begin filming in Italy and New York. Garcia, he was 16 when The Godfather was released, said it would be an honor even to be considered for a role.

Vacationing with his family in Florida, he got a call from Fred Roos, who told him Coppola wanted to meet him, so Andy took the next flight to L.A. The meeting went well. Garcia went back to Florida and waited. There were rumors that Robert DeNiro wanted to play the part of Mancini, Vito Corleone's own grandson, but Coppola decided he was too old. Alec Baldwin was also in the running, as well as Matt Dillon. The director decided to cast the part based solely on the actors' screen tests. Garcia was called once again and invited to come to the Coppola home in Rutherford, California, where scores of other actors were already auditioning. Actress Madeline Stowe had been asked to read with Garcia. They rehearsed three scenes in the morning and did them that afternoon. ("She was a gift from God," Garcia says. "She was great.") Two days later, the deal was done. Garcia, the least bankable actor up for the role, had won it hands down. If the chance to work with Coppola wasn't enough, he would be paid a cool million to play Vinnie. Winona Ryder was cast as Mary Corleone, his love interest.

"It was really Francis's decision," says Garcia. "He told me later that they [Paramount] told him, 'We got a guy we like,' It's, like, 'Oh great. Troy Donahue.' He started to tell me who Paramount wanted to be Mike Corleone in the first movie. So in a way, I was the guy with the worst recommendation.

In November of '89, the cast went to Rome's Cinecittà studios to shoot. There were no scripts. Every morning, Coppola would come out of his trailer with new material. Garcia flourished in the spontaneous working atmosphere Coppola created. But a month after shooting began, Winona Ryder arrived, suffering from exhaustion. When it became clear that she would be unable to do the film, Coppola made an infamous casting decision; his then-18-year-old daughter, Sofia, in Europe on vacation from school, would play Mary. The choice sent shock waves through the cast and crew. Sofia, a novice actress, was emotionally torn. There were tense moments, with the girl often found crying in her trailer.

Throughout the turmoil, Garcia remained calm. On every team, there are substitutions.

"It had a direct effect on him and his character," Roos says, "but he was a total stand-up guy about the whole thing."

"He was generous with her," says Sofia's mother, Eleanor Coppola.

Garcia become Sofia's protector, on and off the screen. "She's a young girl, and she came through with flying colors. To me, she is Mary Corleone," he says. "The fact that she was fresh out of the starting block made it more spontaneous. She was under a great deal of pressure, but she came through."

What seemed to be an eccentric decision turned out to be a smart move; it empowered the love story and gave Garcia an added emotional pull. He locked into Vinnie. "I consider Sofia family. I consider her like a newfound cousin. The whole family - the Corleones, I mean Coppolas." He laughs. "Freudian slip."

Coppola gave Garcia valuable advice on how to play Vinnie: "it was told to me that Vinnie had the temper of Sonny, the smarts and ruthlessness of young Vito, the kind of machinations and calculations and coolness of Michael and the warmth of Fredo." Garcia leans back, taking another sip of rum. "Me and Francis got into a kind of shorthand: 'Okay, this is a Sonny scene. This one is a young-Vito scene. This one is a Michael scene. This one is a Fredo scene.' " So Garcia became a human melting pot, a repository for bits and pieces of the Italian family's complex male personas.

Vinnie grows up in Arizona and spends the first twelve years of his life riding horses. He then turns to crime and kills - according to Garcia - "about twenty people before the age of 30." He's an outsider, and Michael Corleone takes him in. "The more proximity he has to Michael, the more those kind of dormant genes that he has in him multiply and take over. Hopefully, in the third act, he's a different guy than you met in the beginning of the movie."

People who saw a rough cut say that Garcia reads on film much like the young Al Pacino: "Very intense, very serious, slightly dangerous, very street," says producer Fred Roos.

It's a cool September night in Manhattan, and the crew of The Godfather, Part III has cordoned off a section of First Avenue at 33rd Street, at the emergency-room entrance to the New York University Hospital. The scene requires Michael Corleone to be wheeled on a stretcher from an ambulance into the hospital, while Vinnie pulls up in a black car, accompanied by Mary. Crew members mill about, waiting for Coppola to set up the shot.

The production's trailers are lined up caravan style, and from behind one of them a solitary figure in black comes loping down the sidewalk. The walk is cocky but familiar, the arms flailing. It's Garcia, like a taxi with all four doors open, in character: Vinnie Mancini, the killer with the heart of gold. The L.L. Bean watch has been replaced by a thick silver ID bracelet, a sort of Sicilian Rolex. He looks like a goombah, his hair cut and slicked back, his black leather vest and black shirt open at the neck to reveal a patch of dark chest hair.

Garcia is popular with the crew and more accessible than is Pacino, nearly unrecognizable in his nursing-home-issue sweater, steel-gray crew cut and blind-mice sunglasses. While Pacino politely shoos away photographers, Garcia graciously signs autographs, turning on the high beams for a pair of girls momentarily frozen like deer in the glare.

Fred Roos sits in a chair. He hears that Garcia has just posed for a magazine cover. "Did you have your shirt off?" he calls out teasingly.

Sofia Coppola arrives, hugging her rail-thin frame and periodically leaning on Garcia for support. They go through the scene several times, the sickly Pacino being wheeled from the ambulance. Coppola sits in a high-backed canvas chair, a monitor in his lap, yelling orders to "cut." At midnight, the crew breaks and Coppola lumbers off to his trailer.

He and his wife, Eleanor, sit in his trailer, eating sushi and drinking Sapporo beer.

"I didn't know Andy's work at all," Coppola says. "It's true. I didn't like the idea so much that here was the studio's guy. I tested a lot of very good actors. And when I saw Andy, I thought he sort of looked like the family.

"He's very motivated. He approaches it very seriously as an actor and likes it when he can contribute. A lot of times, a director will be working on a scene. The director's sweating, 'How can I make this work?' Andy likes that because he likes to help you organize it."

Earlier, Garcia had said, "A good director, like Francis, will always do takes where he was very specific and then he'll say, 'Okay, this is a free one, say whatever you want. I don't have to use it, but then again you might say one line that I might use.' That's the beauty of film. You get a chance to sift through the raw material, and the more you have, the better off the editing process is going to be. That's really the job of the film actor: to provide an abundance of raw material that's not repetitive."

Garcia is sitting with Sofia in her trailer, also eating sushi and drinking beer. He has called Marivi and the kids several times that day. On Sunday, he wants to relax and watch the Dolphins game on television. He already has another movie to think about, a featured role in Kenneth Branaguh's Dead Again, also for Paramount, scheduled to begin shooting the next month.

But Godfather III is not finished. It is 2 A.M. and the crew has moved to a location on the West Side, where a helicopter scene will be shot. Garcia pops a candy bar in his mouth and jumps in the back of a station wagon, vroom, vroom, going off to work.

William Marquez says he recently ran into an old friend of Garcia's from Miami. Marquez recognized the friend, walking down the Venice, California, boardwalk followed by a pack of dogs, having met him once before with Garcia. The two men stopped to greet each other. The other man asked how Garcia was doing.

"Don't you know?" Marquez replied, laughing. "He's becoming a star."

"Nah, nah," Zoom Zoom Zami replied, over his shoulder. "An-dee was always a star."

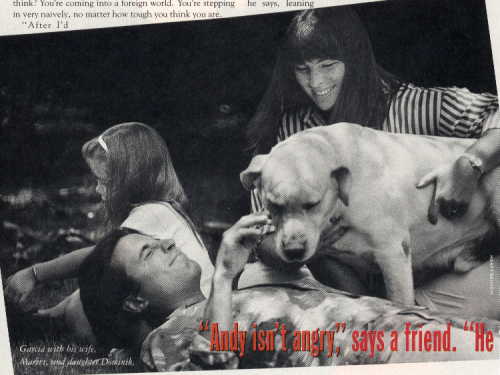

Andy Garcia and his wife, his daughter and his dog.