The Story of the Laframbois Island Struggle

By Jon Lurie, Journalist (c)1999

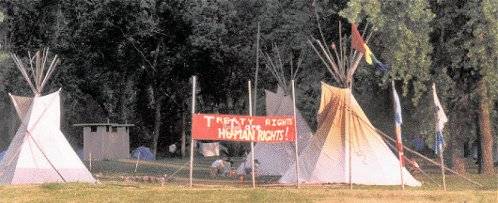

Photo: Zoltan Grossman, Midwest Treaty Network, 1999.

THE MITIGATION ACT

The LaFramboise Island occupation came about in response to an act of Congress, co-authored by Janklow and Senator Tom Daschle (D-SD), which transfers 200,000 acres of prime Great Sioux Nation land to the state of South Dakota. The "Wildlife Mitigation Act" ostensibly seeks to restore lands ravaged by the massive flooding associated with the construction of the Pick-Sloan Dam system, to their original condition. It establishes a $108 million "wildlife habitat restoration trust fund" for the state of South Dakota to spend as it sees fit. The bill was pushed through the Senate Transportation Committee, then tacked on as a rider to a 14,000-page appropriations bill, which President Clinton signed. Approximately 90 percent of the Missouri River banks within the borders of South Dakota will be transferred to the state pending an Army Corps of Engineers environmental impact statement.

Robert Quiver, a former staffer in the Oglala (Pine Ridge) Sioux Tribe's Vice-President's office and an organizer of the Lakota Student Alliance (LSA), was among the first seven activists to encamp at LaFramboise Island. Quiver says the Lakota people feel betrayed because the Black Hills Treaty Council, made up of descendants of the signatories of the Fort Laramie Treaties, was never consulted. "We learned about the transfer by reading it in the paper," Quiver says. "We had no pre-warning. Congress held no oversight hearings. They never put it before the Indian Affairs Committee. The Treaty Council called a special meeting in Rapid City in March. I attended along with several members of the Lakota Student Alliance. We had been to treaty meetings before...We felt that it's time to act. If we lose this it's going to affect all Indian country."

THE CAMP

On the evening of March 22 it began to snow on LaFramboise Island just as the sun was setting. Minutes earlier construction of the camp's first tipi was completed, a fire lit inside. The site of the protest, a picnic grounds that serves as a party hangout for local teens, was chosen for its visibility from both east and west banks of the Missouri River, as well as its proximity to the very government institutions that seized the land. The seven Lakota Student Alliance members in that hastily-assembled camp were without blankets that first night. Their resolve to hold onto their country, they say, kept them going trough the night.

Two months later the LaFramboise encampment has become a small village consisting of five tipis, a sweat lodge, a kitchen fashioned from a picnic shelter, two outhouses and several tents. Many of the Lakota activists have given up homes, relationships, jobs and school to be here. There is a permanent core group of activists as well as a transient population of twenty to thirty supporters from throughout Indian country and the world, including a three-member contingent of international human rights observers from the Chicago-based Christian Peacemaker Teams (CPT).

CPT member Joanne Kaufman says the government has violated basic human rights here in that the Lakota had "land taken from them that was promised in good faith in a treaty. Its been systematically and 'legally' taken from them unilaterally by the US Congress." Kaufman's last assignment was in the Palestinian West Bank. In the town of Hebron she stood face to face with Israeli soldiers preventing them from firing on Palestinian demonstrators.

On Monday, April 20, Kaufman and co-worker Kathleen Kern met with Bob Mercer, Governor Janklow's press secretary, to discuss the situation on LaFramboise Island. "We let him know that we consider this situation as serious as Chiapas and the West Bank," says Kern.

Kaufman says Mercer insisted that recreational development of the Missouri River was the state's only objective. "We asked about industrial development and he flat-out denied that was going to happen," Kaufman says. Kern also contacted the Pierre-based FBI Special Agent Joseph Weir. She says Weir "hoped the FBI would not be called upon to do an eviction," and then called any plan to use them for such a purpose "foolish." Both the FBI and the Janklow administration believe the LaFramboise camp will pack up and go home come fall, according to Kern.

But camp supporters say that won't happen. "We're here to say no. The state isn't entitled to any of this land. This is all treaty land. It belongs to the Sioux. That's who it should go back to. That's why we're going to stay here until this so-called law is repealed and dealt with in the right way," says Dan Merrival, one of the occupation's leaders and a member of the Pine Ridge Sioux Tribe.

THE LAND IN QUESTION

The Food Control Act of 1944 authorized the implementation of the Missouri River Basin Pick-Sloan plan that

allowed for the seizure of treaty lands needed to build the dam system. The Army Corps of Engineers estimates

that the project's overall contribution to the nation's economy averages $1.27 billion annually. For the tribes along the river, however, the human and economic costs has far outweighed any benefits received from the project. Two of its main-stem dams, Ft. Randall and Big Bend, flooded over 22,000 acres of Lower Brule's bottomlands -

resettlement of nearly 70% of the resident tribal population. On the Cheyennne River Reservation the flood waters of Lake Oahe took 104,000 acres of the tribe's bottomlands (80% of the tribe's fertile land), requiring the forced resettlement of nearly 30% of the reservation population, including four entire communities.

The same law that allowed for the taking of the land also promised the return of any acreage that proved non-essential to the system's operation. After extensive study the Army Corps of Engineers determined that 200,000 acres of land along the east and west banks of the river were non-essential.

In 1995 the Corps sought to return 13,500 acres of west bank land to the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. But before the transfer could happen then-South Dakota Senator Larry Pressler brought the deal to a halt with legislation he introduced to congress. Pressler's bill removed "any authority for the Corps to transfer lands in South Dakota acquired by the Corps for construction and operation of reservoirs on the main stem of the Missouri River."

Pressler said he believed it would be "foolish" for the Corps to "politicize the land transfer," while ignoring what he called the "strong public sentiments of South Dakotans." To transfer the land, said Pressler, would "further the belief that a war on the West is being waged by Washington bureaucrats."

Robert Quiver says he would agree that a war is being waged -- a war against the Lakota Nation and the environment. Quiver worries that under state control federal laws protecting Native American sacred and burial sites, of which there are hundreds in the Mitigation area, would not be honored. "I believe that the state won't protect the medicine that grows on the ground here, they won't protect the wildlife...I believe they've mainly interested in commercialization. This land will be exploited. The consequences of development would be that the spirit of mother earth and Wakan Tanka (The Great Mystery) would be under attack," Quiver says.

An April 1999 report by American Rivers says the federal government has done a dismal job of managing the once pristine Missouri River. They rank the Missouri number two on their list of "America's Most Endangered Rivers."

"The river no longer has the natural flow of rising in the spring to trigger fish reproduction, build sandbars and regenerate cottonwoods, followed by declining flows in the summer." Because of this, "nearly 100 Missouri River species are threatened," the report says.

THE GREAT SIOUX NATION

The Great Sioux Nation today exists only on paper and in the heart and minds of the Lakota Nation (named Sioux

by the French who distorted the Ojibwa word for "cutthroat"). The Lakota once enjoyed a much larger territory. But after years of bloody wars, in which they stood as equals against American might (including the obliteration of Custer's army at Little Big Horn), the Lakota agreed to establish their country in the western half of what is today the state of South Dakota. In the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 the United States recognized an independent, sovereign nation--called the Great Sioux Reservation--to be established from the "east bank of the Missouri River" westward to the current state borders. In exchange for peace with neighboring white settlers, roads and rail builders, this land was guaranteed by the United States to be set aside for the "absolute and undisturbed use of the Great Sioux Reservation... No [other] persons... shall ever be permitted to pass over, settle upon, or reside in the territory..."

Article 12 of the treaty states that no land under the agreement can be given or sold by the Lakota people unless signed-away by "at least three-fourths of all the adult Indian males." But within a generation of the treaty's signing, the United States military, eager to open corridors for European prospectors seeking gold in the Black Hills, had forced the seven Lakota bands onto five separate reservations (amounting to 20% of their original territory): Pine Ridge, Rosebud,Cheyenne River, Standing Rock, and Lower Brule.

By the turn of the century the Lakota were prisoners in their own country, robbed of the right to speak their language, practice their religion, raise their children, travel off reservation, or pilgrimage to their sacred Black Hills. In one of the most shameful events in American History, the last free band of Lakota was gunned down in cold blood at Wounded Knee on December 29, 1890 by the Seventh Cavalry. Over 300 men, women, and children were riddled with bullets before being hurled into a mass grave. For 83 years the United States called Wounded Knee a battle, and the Lakota Nation, half underground and half enduring forced assimilation, was unable to tell the world otherwise. That was until the American Indian Movement, a pan-Indian warrior society that grew out of the civil rights struggles of the time, arrived in Wounded Knee in 1973.

WOUNDED KNEE SPARKED LaFRAMBOISE

Robert Quiver was four years old when the American Indian Movement (AIM) came to the Pine Ridge Reservation. He and other members of the Lakota Student Alliance credit AIM with shaping their belief that the Great Sioux Nation can and will live again. Quiver recalls the bloody Pine Ridge civil war that pitted traditional Indians against FBI-backed death squads, called GOONS, or Guardians of the Oglala Nation.

"Our house became an AIM house," Quiver says. "The AIM people would come over for a shower, something to eat, or to rest. We always had tight security in case the GOONs came around. But one day we were on the road and we came up behind a really slow moving truck. Another truck full of GOONs was suddenly on our tail and we were forced to stop. They got out, put a gun to my father's head and ordered two men onto the road. My dad pleaded with them not to shoot because we were there. My baby brother and I were scared and started to cry. Those GOONs aimed their guns at us and said, 'If you don't shut those kids up we're going to blow their heads off.' The GOONs were death squads, just like they had in El Salvador and Guatemala," Quiver says.

On February 27th, 1973, in response to FBI-sponsored violence, the American Indian Movement stood alongside the traditional Lakota people as they took over the tiny village of Wounded Knee. For seventy-one days a group of American Indian Movement (AIM) members (mostly urban people) engaged in a shooting war against the largest internal deployment of federal forces since the Civil War. Two AIM warriors were killed in the fighting. Government assurances to address the Indians' demands prompted an end to the stand-off. But, as with so many other government promises to Native people, they were never fulfilled.

The taking of Wounded Knee arose out of desperation. Over one hundred Indians had been murdered in recent years in white towns surrounding the reservation. Few of these had been investigated and even fewer solved, testimony to the low value assigned to Indian life by local whites. In addition, the United States had installed a puppet administration headed by Dick Wilson, a plumber and part-time bootlegger and a man who, like many of his generation, had no interest in maintaining traditional ways. Wilson handed out lavish salaries to family members while ignoring the needs of traditional people in the district who were languishing in hunger and near total unemployment. In exchange for federal support, Wilson signed away nearly 200,000 acres of reservation land to the federal government, who claimed the space for a bombing range.

What AIM didn't realize was that beneath the bombing range lay the richest deposit of weapons grade uranium on the North American continent, and to what extremes the government would go to have it. Nor were they aware of a federal plot to turn the Black Hills into what one government study called a "National Sacrifice Zone".

In 1971 the Interior Department endorsed a document that declared the Black Hills was to become the nucleus of a massive energy center, producing power in the abundant uranium and coal field, and exporting it eastward on a network of lines running to St. Louis and Minneapolis. This came with an acknowledgment that 188,000 acres would be devastated, while inflicting irreparable damage to the air, land, water, and life on the Great Plains. A toxic smog of nitrogen, sulfur, and ash would cover the skies of the mountain states, and thousands of square miles of creeks and prairie ponds across the country would disappear. The impact statement specified that Indians would lose their "special relationship to the land", as it "shifted to mineral extractive use."

Within a few years over a million acres were claimed by about twenty-five multinationals. The energy companies planned to encircle the Black Hills with thirteen coal-fired plants, producing ten thousand megawatts apiece, with an additional sixty plants under consideration. There would also be a "nuclear energy park" with up to twenty-five reactors. The companies began test drilling for minerals on a grand scale. Leaking uranium holes soon poisoned the Black Hills aquifer, the only source of drinking water in the region, killing cattle in the Southern Black Hills. The $500 million in estimated potential uranium revenue explains the federal zeal to eliminate the American Indian Movement. Wounded Knee was at the forefront of protests that ultimately convinced the Interior Department to retreat.

The renewal of open hostilities between the Lakota people and the United States after eighty-three years of unjust peace would forever change the course of history. Wounded Knee was the catalyst for indigenous resurgence at Oka, Chiapas, and now LaFramboise, and caused the indigenous nations of North America to see sovereignty- cultural, physical, spiritual, and linguistic- as a realistic goal.

What frightens many observers of the current situation in South Dakota are the similarities to the underlying causes of the Pine Ridge civil war. In that conflict the government was after the mineral riches beneath the Black Hills. Mineral wealth, it is feared, is also at the heart of the Mitigation Act.

A proposed environmental impact statement released by the Federal Bureau of Land Reclamation in 1976 discusses the effects of the "marketing of up to one million acre-feet of Missouri River water annually." The need for industrial water in the Upper Missouri River Basin, says the report, "is directly related to the availability, in this region, of about 50 percent of the total United States coal reserves." The report also outlines a proposal to convert the Upper Missouri into an industrial waterway with power plants, strip mines, and fertilizer plants dominating the banks from Montana to South Dakota. There is no language in the Mitigation Act preventing industrial use of the Missouri.

JANKLOW STILL BITTER

William Janklow was the South Dakota Attorney General who advocated the murders of AIM leaders as a solution to protests demanding human rights for Native Americans. The occupation of Wounded Knee sparked a firestorm of anti-Indian hatred across the state to which Janklow owes his political support. Janklow's rabid stand against AIM won him points among white voters and after the successful prosecution of AIM leader Dennis Banks, elevated him to the governor's office. "The only way to deal with the Indian problems in America," Janklow told reporters in 1974, "is to put a gun to the AIM leaders' heads and pull the trigger."

Twenty years later Governor Janklow continued using anti-Indian rhetoric for political gain. Before an all-white audience in 1994, Janklow claimed that South Dakota tribes were engaged in a "master plan" to takeover all of South Dakota west of the Missouri.

Earlier that year, in a pre-election edition of South Dakota Public Television's Buffalo Nation Journal, Janklow ended a debate by giving a five minute closing statement in the Lakota language.

Mary Witter, a non-Indian supporter of AIM living on Rapid City, said Janklow's message to the Lakota people was that, "he was with them, he was one of them. His whole campaign was run on his support and caring for the Indian Nations, and how much he's done for the Indian people. Janklow was dropping names of all the Indian people he knows and all the reservations he's been to. It was pathetic, and people fell for it. You could see the white middle-class sitting in their homes thinking, 'This guy's going to do alright by those poor Indians.'"

Witter said Janklow spoke throughout his campaign about economic development on the reservations, doing this through proper channels, by setting up funds and hiring contractors. "He never said what kind of economic development he had in mind, it was always very general. I didn't get the feeling that he was at all genuine to the traditional people I'm concerned he'll make a bigger push for assimilation," said Witter.

In early 1983, Janklow filed suit against author Peter Matthiessen seeking $24 million in damages. Among other things Janklow was upset about being portrayed as a "racist and bigot" and "an antagonist of the environment". Matthiessen's book, "In the Spirit of Crazy Horse", documents the alleged rape of a 15 year old Lakota girl who later turned up dead on a barren stretch of Nebraska highway. Janklow was charged with rape in Rosebud tribal court but left the reservation rather than face trial. In 1988, the South Dakota Supreme Court dismissed Janklow's suit against Matthiessen.

"I think Janklow's still bitter about what happened during the Wounded Knee days," says Robert Quiver, "and I think he's still vindictive toward Indian people because of that book."

The Janklow administration has turned down requests from media and the Lakota Student Alliance to publicly debate the Mitigation Act.

AIM: THE NEXT GENERATION

The Lakota Student Alliance might be called AIM: the next generation. Among the activists on LaFramboise most had parents involved in Wounded Knee and other AIM activities. While there are older AIM members at the camp, it is the twenty and thirty year olds from the LSA who are in charge. They have taken their inspiration from AIM struggles of the past, but are looking to the future with a vision of their own.

"Wounded Knee was more about anger and direct confrontation," says Robert Quiver. "It was good that it happened. Without that we would not have been able to stand up here. The difference between us and Wounded Knee is nothing bad. It's just a different method. We're trying to encourage our youth by showing them there are different methods, spiritual and peaceful methods, available to the movement. We want to destroy the myth that AIM is a militant group of hell raisers. We have to let South Dakota know that we're here in peace," says Quiver.

Twenty-three year old LSA member Wambli Yellowbird remembers his father Bob Yellowbird. Yellowbird is remembered as one of the first Lakota men of his generation to stand-up against racism in the white Nebraska communities bordering the Pine Ridge reservation. Wambli keeps a scrapbook in his tipi of yellowing photographs and newspaper articles showing his father, in braids and headband, taking-on white government councils in towns like Gorden and Chadron, Nebraska.

"My dad liked to shoot people," Wambli says. "He had a quick temper and wouldn't take no abuse."

Wambli says he realized there might be a better way to deal with conflict after watching his father suffer for most of his life.

"We're going to have to go non-violent here. I don't think showing violence to anybody would really solve anything," he says. Yellowbird add that his attitude might change if the state began industrial development of the Missouri. "If it came down to action I know what I'd have to do, and I'd be ready to lay down my life for my people." Yellowbird says his father taught him to always be in the front lines protecting the Lakota Nation.

"If we let this happen pretty soon we're going to have no place to live. I think they've taken enough land. What little bit we have left they should leave us alone on it. There was an agreement. We were supposed to get the land back when the government was done with it. I think they should have kept their word on it," says Yellowbird.

Edgar Bear Runner, an elder advisor to the camp who fought at Wounded Knee, has nothing but praise for the non-violent tactics of the Lakota Student Alliance, but says he is worried about the lack of attention by the local and national press. "Indian issues have always taken a back seat. When you're doing something good you don't get media coverage. But as soon as you break a window or burn something you get front page coverage," he complains.

TALKING TO THE WRONG CHIEFS

LaFramboise activists are also upset at one of their own--Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe President Gregg Bourland--who they say conspired with Janklow and Daschle to write the mitigation legislation. In exchange for his signature Bourland's reservation will share a $57 million "wildlife trust fund" with its down river neighbor, Lower Brule, whose government also signed onto the Act. Under the agreement both reservations will also take control of their Missouri banks.

Dan Merrival says that once again the United States is deciding who the Lakota chiefs will be. "Bourland is not a treaty leader. He's only a quarter Lakota and he doesn't represent our nation. He is not even a member of the Treaty Council," Merrival says.

District 6 of the Cheyenne River Reservation voted to impeach Gregg Bourland for treason against the Great Sioux Nation. Bourland himself wrote to President Clinton asking for a veto complaining that the language in the bill was changed at the last minute. "This is not the language we agreed to. Someone changed it without consulting us," Bourland claims.

A SPIRITUAL CAMP

LaFramboise is a spiritual camp. Its inhabitants begin the day by offering tobacco to the sacred fire and to the waters of the river. They spend their time in council, cooking, singing, sweating, drumming, chopping wood, gathering water, and maintaining security. Organizers don't allow weapons or drugs but say anyone is welcome to come, stay, contribute and learn as long as they "come in a good way."

Some of the local visitors to LaFramboise have failed to follow camp protocol. Ron Eastman, a Native activist from Wisconsin, says he was nearly run down in a racist attack near the island. "I was walking to the phone,"says Eastman. "On my way back a car circled me twice then it came back and pulled to the side. When I walked by it they said, "you f-ing timber niggers, why don't you go back to your reservation.' Then they squealed out and came inches from hitting me."

"The young white people come by and holler racist, obscene gestures. We just let them say it. These are drunk little white boys who don't know any better," says Rick Greybuffalo. But on the night of Sunday, May 2, the situation turned ugly when a white Dodge van containing several young white males shot at the camp as they drove by. No one was injured. Three people in the camp identified the van to Pierre police. No arrests have been made.

TREATY RIGHTS VALID AS CONSTITUTION

LaFramboise activists say that when the United States fails to honor its treaty obligations it is breaking its own laws. Article 6 of the US Constitution states that treaties are "the supreme law of the land," and activists say treaty lands cannot be taken unilaterally by an Act of Congress. In addition, the US Supreme Court recently upheld the treaty rights of the Chippewa to hunt and fish in unceded territory in Minnesota (Minnesota v. Mille Lacs Band). A similar Supreme Court ruling, upholding the spirit of the 1868 treaty concerning use of Missouri River lands, was made in favor of the Lakota in 1993 (South Dakota v.Gregg Bourland).

Activist say they only want the government to abide by its own policies, such as the Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies issued by President Clinton on May 3rd, 1994. It orders government leaders to "consult...with tribal governments prior to taking actions that affect federally recognized tribal governments. All consultations are to be open and candid so that all interested parties may evaluate for themselves the potential impact of relevant proposals."

Edgar Bear Runner says all people should take notice when a government is above the rules it makes for its people. "It disturbs me to see covert meeting between Daschle and Janklow that will decide our fate," he says.

THE CONSEQUENCES OF FAILURE

"The consequences of failure would be that we would lose the bulk of our treaty rights, the rights that were described in the 1851 and 1868 Fort Laramie treaties. Those rights will be weakened and will be reflected on by the Supreme Court decision in the future that will be against the treaties. The second consequence will be that we'll lose our land, our culture, and our way of life," says Quiver.

Lakota author Charmaine White Face, writing in Rapid City Journal April 17, 1999, quips that the Lakota people should actually thank Bill Janklow and Tom Dasche for forwarding the cause of the Great Sioux Nation. "A few year ago I said they were trying to divide the tribes. Their actions have not divided the tribes. Instead, their efforts to push through the Mitigation Act are bringing us together."

Contact the LaFramboise Resistance Camp:

c/o The South Dakota Peace and Justice Center

PO Box 405

Watertown, SD 57201

Milayatapika News, Porcupine SD

25 yrs Anniversary: Tipi's standing in Blizzard

A Fire That Burns

by Ian Record with Photos by Anne Pearse Hocker

Native Americas Magazine Spring 1998

Vol. XV No. 1

PO Box 225

Kyle, SD 57752

lakotastudentalliance@yahoo.com